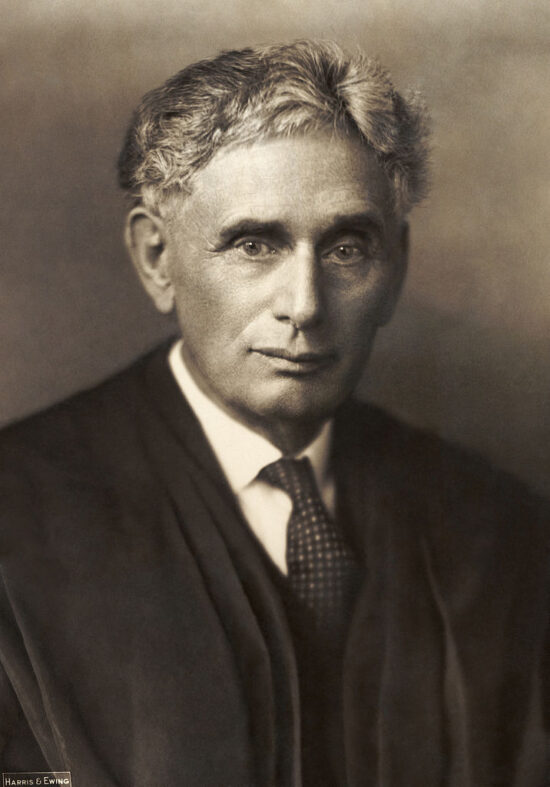

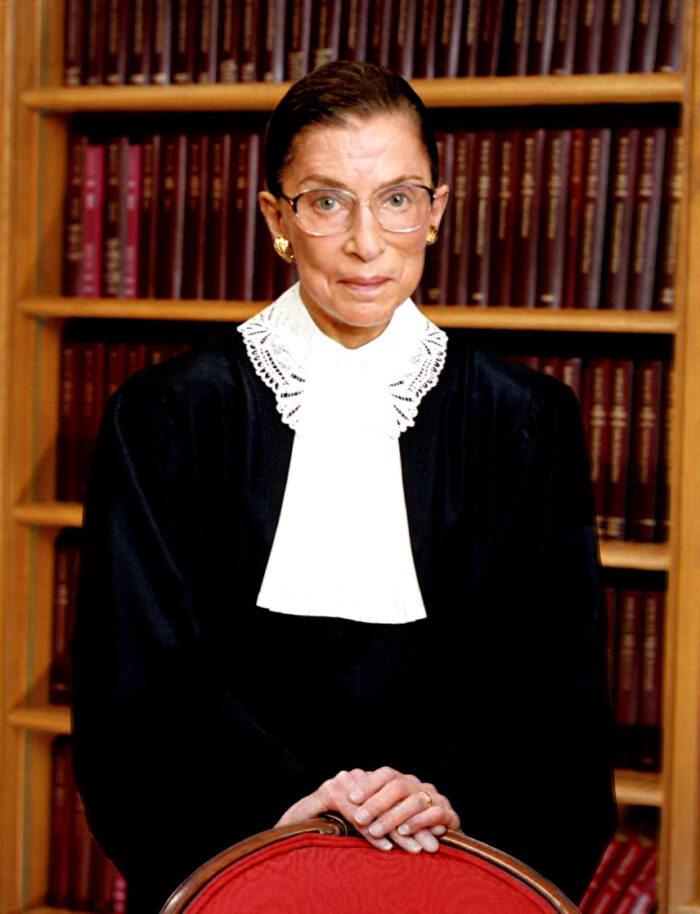

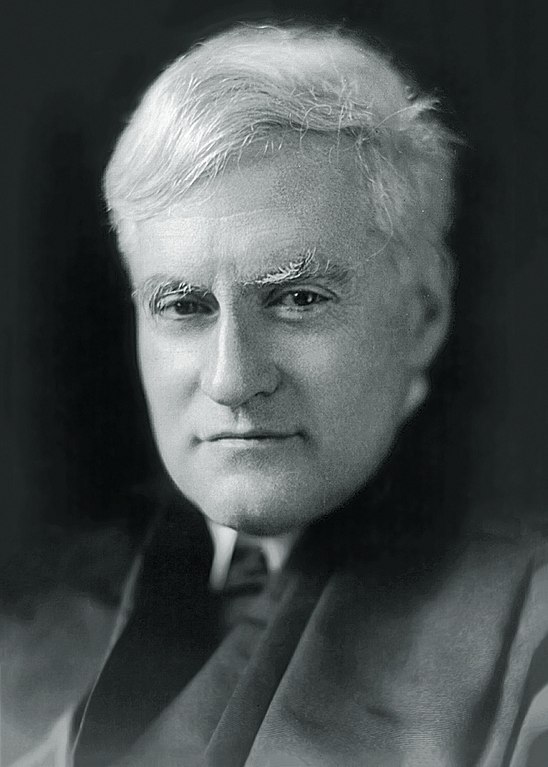

Of the eight Jewish justices who have sat on the U.S. Supreme Court since the appointment of Louis Brandeis in 1916, Ruth Bader Ginsburg held the record for longevity. Ginsburg, who died of cancer on September 18 at the age of 87, served for 27 years, four more than Felix Frankfurter, who was appointed in 1939.

The scion of a Russian father and a Hungarian-born mother whose family immigrated to the United States when she was four months old, Ginsburg was the second woman to serve on the Supreme Court after Sandra Day O’Connor.

She was one of three Jewish judges on the court, a record-breaking number. Her colleagues were Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan.

An indefatigable advocate of gender equality, Ginsburg was a liberal who forged an unusual friendship with one of the court’s most conservative members, the late Antonin Scalia. Together with Breyer, Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor, she formed its liberal wing, though she sided occasionally with the conservatives.

Nominated by President Bill Clinton, following the retirement of Byron White, she won acclaim by writing strong dissents in high-profile cases ranging from affirmative action to birth control.

She is probably best remembered and appreciated for her tireless advocacy of women’s rights. “Equal justice under the law requires all arms of government to regard women as persons equal in stature to men,” Ginsburg, a feminist icon, said.

Born in 1933 in Flatbush, a neighborhood of Brooklyn, she studied at Cornell University, where she met her husband, Martin, on a blind date. After graduation, she worked in Oklahoma for the Social Security Administration. When Ginsburg’s supervisor discovered she was pregnant with her first child, he demoted her. In the 1950s, discrimination against pregnant women was legal in the United States.

In 1956, Ginsburg was one of nine women in a class of 500 to be accepted to Harvard’s Law School. Much to her probable chagrin, the dean rhetorically asked the female students how they could justify taking the place of men.

When her husband, a tax lawyer, obtained a new position in New York City, she transferred to the Columbia Law School to finish her degree. Although she tied for first place upon graduation, she was unable to find a job.

“Not a law firm in the entire city of New York would employ me,” she later said. “I struck out on three grounds. I was Jewish, a woman and a mother.”

Hired as a professor by Rutgers University during the emergence of the women’s rights movement, she taught some of the country’s first courses in women and the law. Subsequently, she became the first tenured female professor at the Columbia Law School.

As well, she co-created the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union. And from 1971 onward, she won five of six sex discrimination cases before the Supreme Court.

In her first court appearance, Reed vs. Reed, she argued that men should not automatically be chosen over women as estate executors. The majority of justices agreed, striking down for the first time a gender-based biased law.

A few years later, in Weinburger vs. Wisenfeld, she successfully argued that a widower is entitled to childcare benefits.

As a jurist on the Supreme Court, following a 13-year stint on the U.S. Court of Appeals, she continued to fight for gender equality. In 1996, three years after appointment, she wrote the majority opinion in United States vs.Virginia, in which she struck down as unconstitutional the Virginia Military Institute’s admission policy of barring female students.

Writing in The New York Times, two of Ginsburg’s former law clerks, Abbe Gluck and Gillian Metzger, observed, “Her once-radical vision of gender equality penetrated the law in countless areas, not just reproductive rights but also workplace discrimination, class-action law, criminal procedure — in every aspect of how women interact with the world.”

Ginsburg’s commitment to equal rights was rooted in her Jewish upbringing. She was of the view that “the demand for justice runs through the entirety of Jewish history and Jewish tradition.”

Laws protecting “the oppressed and the poor” were evident in “the work of my Jewish predecessors on the Supreme Court,” she noted, referring to, among others, Benjamin Cardozo, Abe Fortas and Arthur Goldberg.

As Bill Clinton said, she believed that “our legal system” should “protect all American people, not simply the powerful.”

Ginsburg made a stellar contribution in fostering equal opportunities for women. This is the unforgettable legacy she leaves behind.