This is a country with no religious toleration for non-Muslims — an absolutist entity with no democratic institutions. And it beheads people on a regular basis.

It espouses an austere, puritanical and absolutist Islam, with incitements to jihad and conquest, and tries to export it to other countries.

Apostates from Islam, homosexuals, and blasphemers can face brutal persecution and death. Women are forbidden to drive or get jobs without permission from male relatives; all education is gender-specific.

Are we talking about the so-called Islamic State that now occupies large swaths of Iraq and Syria? No. We are referring to an American ally — the kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab arrived in the central Arabian state of Najd in 1744, preaching a return to a “pure” Islam. He sought protection from the local emir, Muhammad ibn Saud.

In return for endorsing al-Wahhab’s form of Islam, now known as “Wahhabism,” Ibn Saud would acquire political legitimacy. The religious-political alliance that they forged endures to this day in what is now Saudi Arabia.

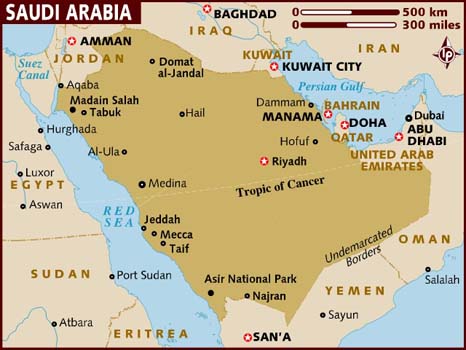

Saudi Arabia’s king is formally known as the “Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques” (in Mecca and Medina). The kingdom is governed by Islamic sharia law. No other law is deemed necessary and no contrary law is permissible.

The kingdom is patrolled by a religious police force that enforces the niqab for women. In the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, the religious police beat women with sticks if their dress is considered immodest by Wahhabi standards.

Saudi Arabia forbids non-Muslim religious practice. For instance, on Sept. 5, Saudi police raided a house in Khafji, near the Kuwaiti border, and charged 27 Asian Christians with holding a church ceremony.

In the space of 18 days during August, the kingdom beheaded some 22 people, according to human rights advocates; it carried out a total of 79 executions last year. Many of those killed were convicted of relatively minor offences, such as smuggling hashish. There are also public whippings for various offences.

Saudi Arabia has no civil penal code that sets out sentencing rules, and no system of judicial precedent that would make the outcome of cases predictable based on past practice.

“Any execution is appalling, but executions for crimes such as drug smuggling or sorcery that result in no loss of life are particularly egregious,” says Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East and North Africa director for Human Rights Watch.

Partly in reaction to the Shia resurgence in Iran, Iraq and Lebanon after 1979, Saudi Arabia, in order to assert its fundamentalist Wahhabi ethos, became stricter in its application of Islamic law, and increased its financial aid to ultraconservative Islamists and their schools throughout the world.

For decades now, Saudi Arabia has been the official sponsor of Sunni Salafi Islam (of which Wahhabism is one form) across the globe, funneling support to clerics, satellite networks, political factions and armed groups. Al Qaeda, Nigeria’s Boko Haram, and the Somali al-Shabab are all violent Sunni Salafi groupings.

The Saudi government has appointed emissaries to its embassies in Muslim countries who proselytize for Salafism. The kingdom also bankrolls ultraconservative Islamic organizations like the Muslim World League and World Assembly of Muslim Youth.

Textbooks in Saudi Arabia’s schools and universities teach this brand of Islam. The University of Medina recruits students from around the world and sends them to Muslim communities in the Balkans, Indonesia, Bangladesh and various African countries.

Dissidents in Raqqa, the Syrian town that is the Islamic State’s capital, have said that all 12 of the judges who now run its court system, adjudicating everything from property disputes to capital crimes, are Saudis.

Yet Saudi Arabia is considered by Washington an important American ally. Western countries, who need Saudi Arabia’s oil and see it as a counterweight to Iran, have turned a blind eye to most of this.

Such is the practice of realpolitik in a volatile Middle East.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.