Saudi Arabia was mired in the medieval past when American prospectors discovered oil deposits beneath its desert sands in 1938.

Prior to this seismic event, the Arabian peninsula had hardly changed in centuries, its deeply conservative inhabitants still dependent on traditional ways of earning a livelihood –raising livestock, working in agriculture, fishing and pearl diving, or running small businesses. During this pre-modern era, the Saudi government’s main source of income came from taxes and revenue generated by the hajj, the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina.

The discovery of petroleum transformed Saudi Arabia into a Middle Eastern powerhouse. Before statehood in 1932, Saudi Arabia was composed of four distinct and separate regions with a largely illiterate and pastoral population.

This transformation, one of the most astonishing in history, is the subject of Ellen R. Wald’s cogent work, Saudi, Inc. — The Arabian Kingdom’s Pursuit of Profit and Power, published by Pegasus Books. Wald, an American historian and consultant, focuses on the period from the 193os to the present.

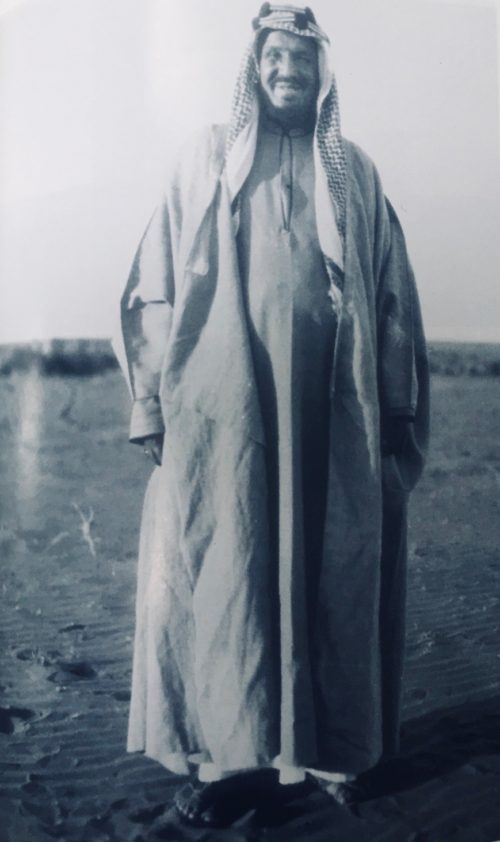

In 1933, the Saudi king, Abdul Aziz, signed a concession agreement with an American company that would later be known as Aramco. The pact was signed in Jeddah, the only Saudi city where foreigners were allowed to live. At that juncture, the United States did not even have an embassy in Saudi Arabia, the seat of Islam. Indeed, the first U.S. ambassador did not arrive until the summer of 1946.

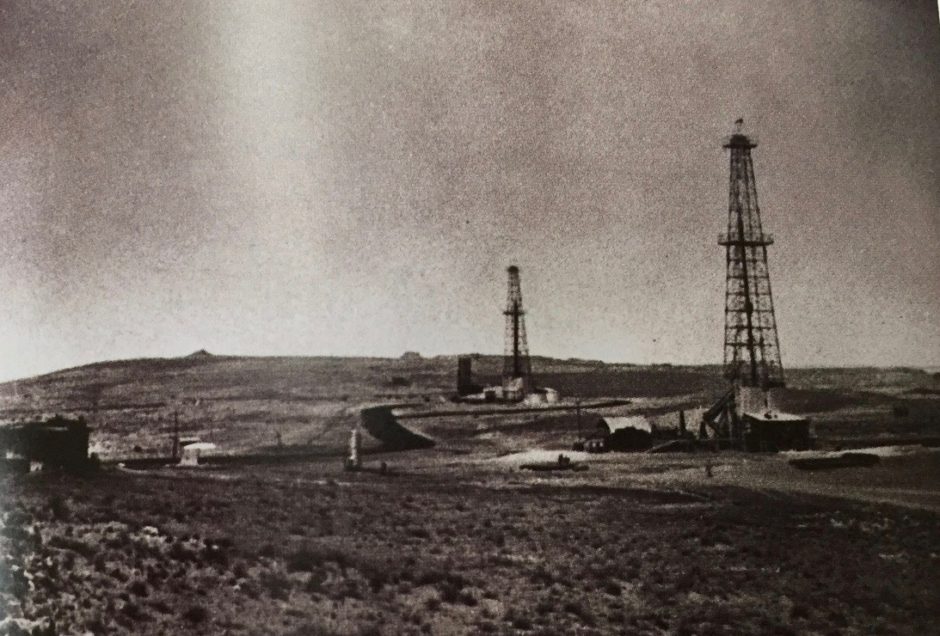

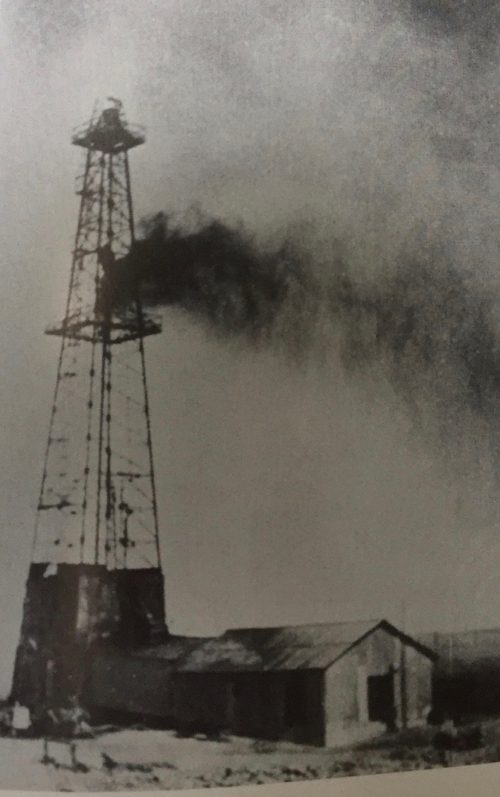

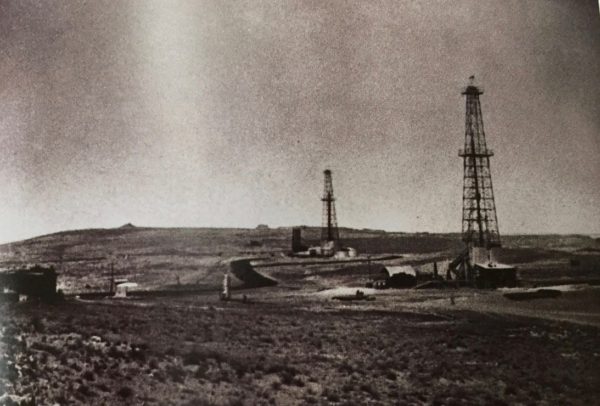

The inaugural Saudi well produced 1,585 barrels a day. By 1947, Saudi wells were producing more than 200,000 barrels daily. With demand for oil quickly soaring, particularly in western European countries recovering from World War II, Aramco began building an extensive network of roads, dormitories, airfields, pipelines and deep-water ports to accommodate the rapidly increasing flow of oil.

Much to the relief of the United States, Abdul Aziz assured Aramco that he would not permit the Arab-Israeli conflict to interfere with the production of oil.

He was a pragmatist. Oil royalty payments enabled the Saudi royal family, the world’s wealthiest, to enjoy a far more opulent lifestyle, consolidate their grip on power and improve the lives of their people through public works projects ranging from the construction of schools to hospitals. “Abdul Aziz took a risk when he invited the Americans into Saudi Arabia to look for oil,” writes Wald. “That risk paid off.”

With the Saudis demanding a hefty increase in royalties, Aramco offered them a 50-50 profit-sharing deal. Venezuela, in 1943, acquired a similar concession from two big oil companies, Jersey Standard and Royal Dutch Shell.

Despite the Arab-Israeli dispute, Abdul Aziz’s successors managed to maintain good relations with the United States. During the 1973 Yom Kippur War, however, the Saudis and other Arab producers imposed an oil embargo on the United States that lasted several months.

In 1980, the Saudis bought Aramco, but full ownership made no substantive difference because it enjoyed virtual operational independence, says Wald.

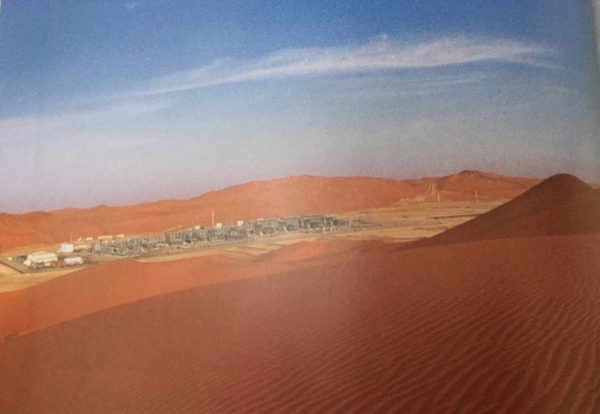

By the early 1990s, Saudi Arabia was the world’s top oil producer.

With reserves of about 263 billion barrels, Saudi Arabia was pumping 12.5 billion barrels per day in 2016. According to Wald, the Saudis will not deplete their reserves for at least 70 years if they produce 10 million barrels a day.

This calculation does not include the likelihood of fresh oil discoveries, the advent of new technologies to improve the rate of recovery, and the growing importance of solar energy, an up-and-coming sector the Saudis are seriously exploring and exploiting.

It would appear that the Saudis have little to worry about economically. Oil has been their salvation.