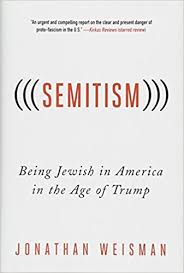

Jonathan Weisman’s cri de coeur, Semitism: Being Jewish in America in the Age of Trump (St. Martin’s Press), is unsettling.

Published several months before 11 Jews were slaughtered by a crazed neo-Nazi in the Tree of Life Congregation massacre in Pittsburgh on October 27, it’s a polemic on the alt-right and antisemitism set against the backdrop of Donald Trump’s tumultuous presidency.

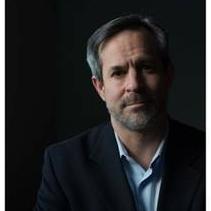

Weisman, the deputy Washington editor of The New York Times, has felt the sting of antisemitism, having personally come under attack by a wave of haters on social media platforms.

From August 2015 to July 2016, he says, 2.6 million antisemitic messages were posted on Twitter, of which 19,253 were directed at journalists. Of the more than 800 journalists subjected to anti-Jewish slurs, 10 were singled out 83 percent of the time. “I was number five on the Top Ten list,” he writes. “Number one was Ben Shapiro, an apostate who had left Breitbart to assume a position in the vanguard of the Never Trump movement of conservatives.”

Weisman was bombarded by these venomous messages by way of emails and voice mails. He was surprised.”I hadn’t known that a virulent antisemitism still existed in America; now, I couldn’t avoid it.”

The messages were always the same: Jews are fifth columnists and traitors. Jews are rapacious Wall Street profiteers and leftist anarchists. Jews are moneybags orchestrating wars on behalf of Israel. Jews are all-powerful.

Andrew Anglin, the founder of the Daily Stormer website, has played a vital role in this verbal onslaught. As he wrote in his typically simplistic style, “It is now fully documented that Jews are behind mass immigration, feminism, the news media and Hollywood, pornography, the global banking system, global communism, the homosexual political agenda, the wars in the Middle East and virtually everything else the alt-right is opposed to.”

Weisman, a self-described assimilated Jew whose wife is a Pentecostalist Christian, contends that Judaism in America was “easy” before the Trump epoch: “It was cafeteria-style: observe or don’t, join a synagogue or attend the occasional Jewish film festival, read Philip Roth, eat bagels and babka, say ‘oy’ ironically. You could be Jewish by religion, Jewish by culture, Jewish by birth or identity — take your pick.”

Naively, he adds, “Antisemitism was in the past. The ‘Jewish Question’ was little worth mentioning.”

But then came the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, during which hordes of neo-Nazis and white supremacists carried offensive placards and chanted, “Jews will not replace us.”

By that point, Trump was president, a prospect that liberals like Weisman had dreaded.

Weisman is profoundly anti-Trump, and Semitism is impregnated with this unabashed partisanship. “Whether he knew it or not, Donald Trump ran the most antisemitic presidential campaign in modern American history,” he claims, citing his ads denouncing “global special interests” and lambasting Janet Yellen, the chairman woman of the Federal Reserve, and Lloyd Blankfein, the chairman of Goldmann Sachs.

Trump’s “America First” slogan, he points out, was borrowed from Charles Lindbergh’s ethnocentric America First Committee, which claimed that Jews, among others, were driving the United States toward a war. In 1941, less than three months before the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, he wrote in his diary, “We must limit to a reasonable amount the Jewish influence. Whenever the Jewish percentage of the total population becomes too high, a reaction seems to invariably occur. It is too bad because a few Jews of the right type are, I believe, an asset to any country.”

In Weisman’s view, the spirit of the 1920s and 1930s, perhaps the darkest two decades for American Jews, has returned in the form of anti-immigrant fervor laced with antisemitic undertones.

From the moment he announced his candidacy, Weisman argues, Trump embraced the cause of white nationalism, “dismissing Mexicans as rapists and criminals, declaring America’s inner cities to be wastelands of carnage, crime and depravity, and lumping all Muslims together under the umbrella of Islamist terror.”

After Trump announced he would ban Muslims from entering the United States, the Daily Stormer exulted, “Get all these monkeys the hell out of our country — now! Hail Donald Trump — the ultimate savior.”

Trump’s association with white nationalism is such that, on October 28, a group of Pittsburgh Jews asked him to cancel his visit to the city unless he changes his ways. As they wrote in an open letter, “Your policies have emboldened a growing white nationalist movement. You yourself called the murderer evil, but yesterday’s violence is the direct culmination of your influence.”

To be fair to Trump, Weisman concedes he was not the first politician to pander to the far right. When Patrick Buchanan sought the Republican presidential nomination in 1992, he stoked nationalist, exclusionist ideas and appealed to white fears of a rising non-white majority.

As far as the alt-right is concerned, Jews are the enemy.

The Jew is shiftless, cowardly, weak, duplicitous and manipulative, constantly urging the United States to go to war on Israel’s behalf. Yet the alt-right is pro-Israel, believing that American Jews should leave the United States and settle in Israel.

Richard Spencer, one of the alt-right’s ideologues, has described his movement as “a sort of white Zionism.” The white ethno-state he envisions would resemble Theodor Herzl’s Alteneuland, the title of his utopian novel.

Weisman suggests that American Jewish conservatives, whom he broadly refers to as “Jewish tribalists,” were only too glad to overlook unsavory aspects of Trump’s policies because of his pro-Israel position. This fixation on Israel, he thinks, could well be counter-productive.

“The American Jewish obsession with Israel has taken our eyes off not only the politics of our own country, (but) the growing gulf between rich and poor and and the rising tide of nationalism,” he says. “Jews have become so obsessed with Israel that the overt and covert signals of antisemitism beamed from the interior of the Trump campaign appeared to be disregarded by people.”

Trump has kept his promises to pro-Israel supporters, having moved the American embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and having withdrawn from the Iran nuclear agreement. But in Weisman’s judgment, Trump has fallen short of the mark in other respects.

Two examples: When he visited Warsaw during his first year in office, he broke with presidential tradition by failing to stop at the iconic Warsaw Uprising monument. This was a blip on the screen compared to his mild characterization of the alt-right in Charlottesville and his shocking delay in issuing a full-throated condemnation of the white supremacist driver who killed a bystander, Heather Heyer, in that Virginia town.

In closing, Weisman says that Americans can counter the alt-right by forming interracial and interfaith alliances, challenging its representatives in courts, and taking to the streets in nation-wide demonstrations.

“This is an era that calls for fearlessness, not heedlessness … We as Jews are strong in our cohesion and have everything to gain by standing up for our commitment to liberal internationalism … We are strong, but sadly, too many of us have taken advantage of that strength to retreat from collective conscience, to let justice be someone else’s problem.”

It’s something to think about, especially after the heartbreaking events in Pittsburgh.