Seventy five years ago this month, two Polish Jewish refugees and their infant son arrived in Canada, a distant nation of peace, tranquility and stability and their future place in the sun.

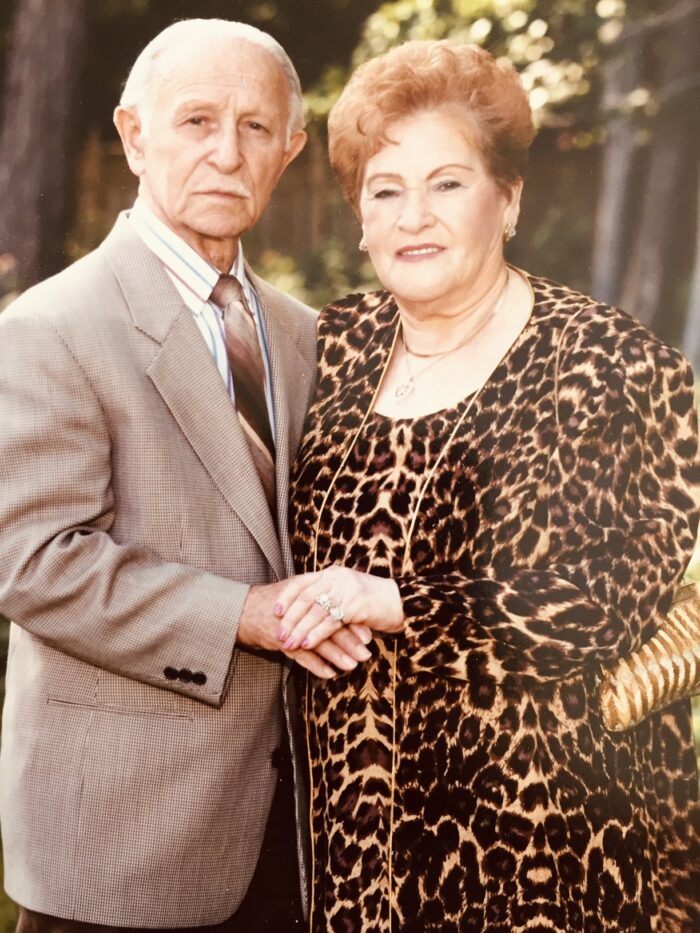

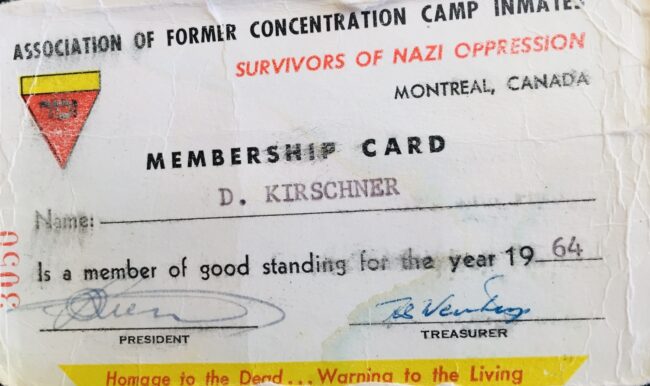

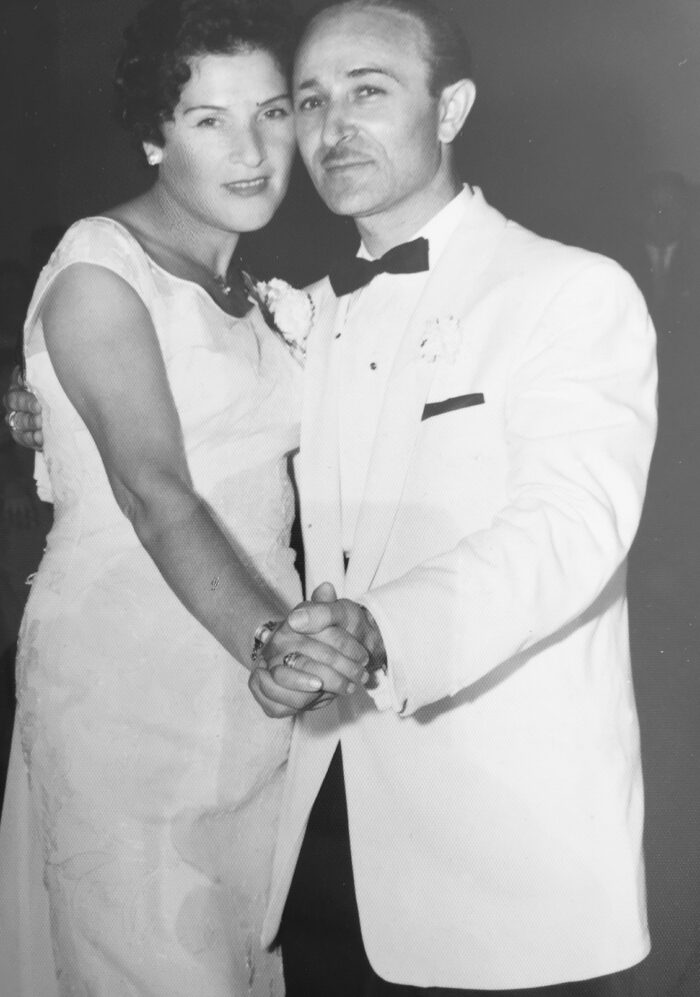

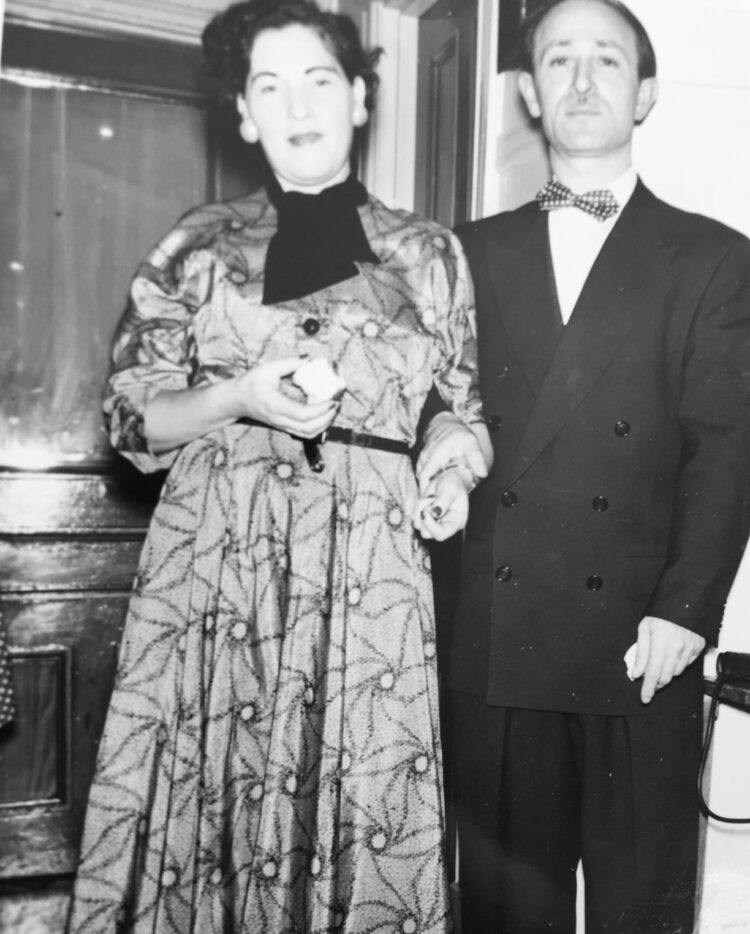

David and Genia Kirschner, my parents, were Holocaust survivors in their early thirties when they set foot in the new world in the hope of restarting their lives on a completely new and firmer footing. Shortly after arriving in Canada, they shortened their surname to Kirshner.

Like all the greenhorns who would become Canadians, they were survivors par excellence, having barely scraped through the tumultuous upheavals and constant existential dangers of a brutal Nazi occupation in Poland and an incredibly destructive European war.

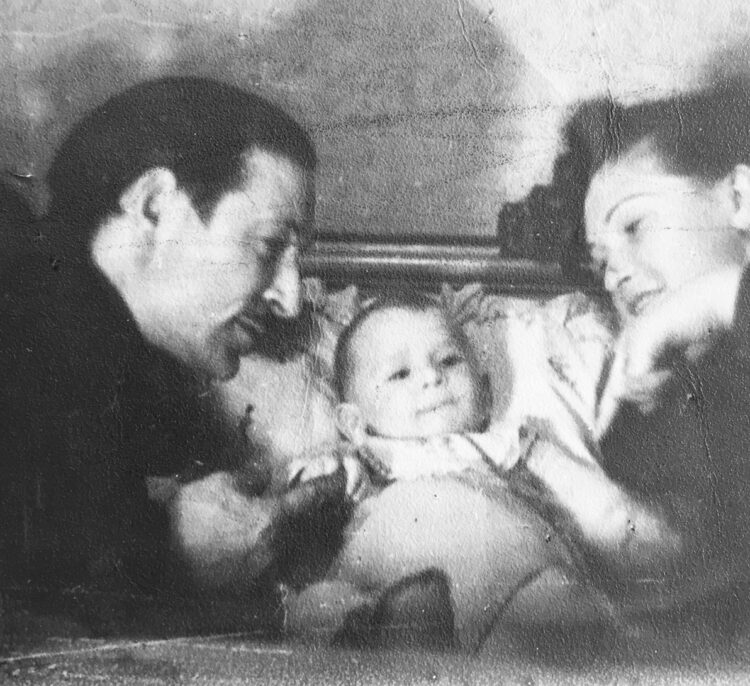

Before embarking on their journey to Canada, they spent about three years in a displaced persons camp in Germany, where I was born. This is where they gradually acclimatized themselves to freedom and a normal life again.

Like some of their closest relatives in Europe who had preceded them to North America, they could have immigrated to Palestine/Israel or the United States. But due to a garment workers program supported by the Canadian government, they chose Canada, which had greatly restricted Jewish immigration until the late 1940s.

Thanks to this special program, my father, a master tailor, had a job waiting for him in a clothing factory in Montreal, which had the largest Jewish community in Canada. For the next three decades, they resided in Montreal — a lovely city crowned by a wooded park and a mountain — until joining their three children in Toronto.

I left Montreal in September of 1969, having enrolled in the University of London’s Middle Eastern studies program. Having earned an MA degree, I was done with London and went back to Montreal in the following year. In the winter of 1971, I found myself in Israel. This is where I would meet my wife, Etti, a student of English literature at Tel Aviv University. She would be the mother of our two lovely daughters, Mia and Lauren.

I lived in Israel for two-and-a-half years, studying and working. At Haogen, a kibbutz near Israel’s old border with the West Bank, I learned rudimentary Hebrew and picked grapes and melons. I was then gainfully employed as a writer at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and Motorola in Tel Aviv.

Toward the end of 1973, in the wake of the Yom Kippur War, Etti and I settled in Toronto, which has been our home ever since. From 1974 until 2013, I was a journalist on the staff of The Canadian Jewish News and freelanced for newspapers in Toronto.

When we landed in Halifax on February 6, 1948, my parents knew nothing about Canada other than it was a prosperous and peaceful land. Having been born and raised in Lodz, an industrial city brimming with textile factories, they expected to live out their lives in Poland. But this expectation was shattered into a thousand shards when Germany invaded and occupied Poland on September 1, 1939.

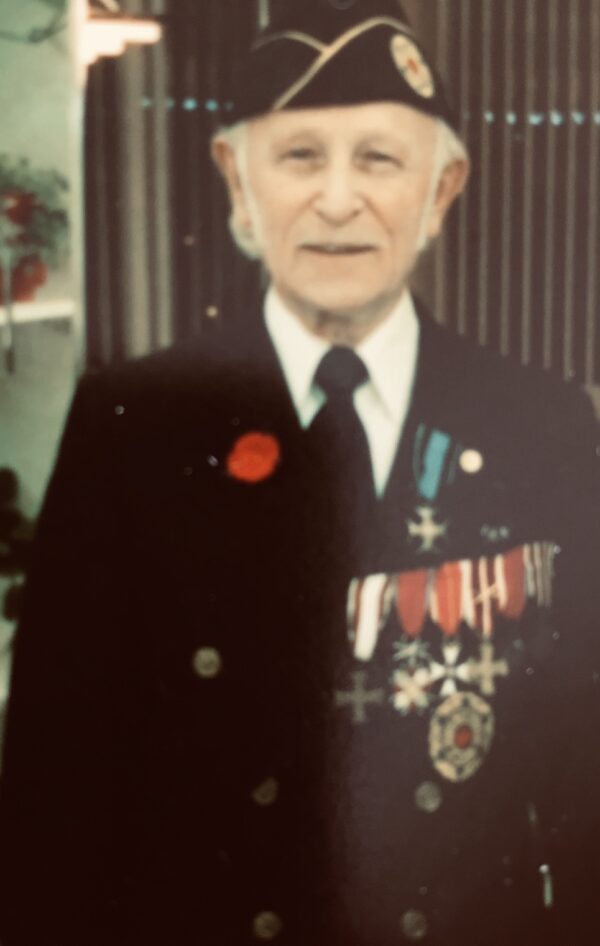

My father, a reservist in the Polish army who had completed his military training in Poznan, was called up for duty shortly after the invasion. Wounded in a battle, he was captured by the Germans. After his recovery in a German hospital, he was sent back to Lodz, whose Jewish residents were segregated in a sealed and congested Nazi ghetto from 1940 to 1944.

Ghetto inhabitants were subjected to a starvation diet and horrific living conditions. Deportations to Nazi extermination camps gradually reduced the Jewish population. My father survived because he was a fireman, a coveted job in the ghetto. I’m not certain how my mother managed to survive. What I do know is that she married her first husband, and gave birth to a boy, before the war.

Although the ghetto produced essential goods for the German army, it was liquidated in August 1944, the last one in Nazi-occupied Poland to be closed. By that point, more than 90 percent of its population had died of starvation or disease or had been murdered in Nazi death camps.

Genia and David, along with thousands of survivors, were rounded up and taken to a train station in Lodz and transported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. My mother lost her son upon arrival. In a cruel and clinical selection process, he was assigned to another line, never to be seen again. Presumably, he was killed after being herded into a gas chamber. This grievous loss tore a gaping hole in my mother’s heart and haunted her for the rest of her days.

How David and Genia survived this unfathomable ordeal I will never know. But they were both strong and resilient and were determined to outlive their Nazi tormentors.

I have no idea how long they were imprisoned in Auschwitz-Birkenau, where 1.1 million Jews perished. When I asked them that question, their emotional reaction was such that I immediately drew back, realizing I had crossed into forbidden territory. Having learned that the Holocaust was an extremely sensitive and painful topic, I generally avoided it, even as I steeped myself in its gruesome intricacies. In retrospect, I regret not having probed for answers.

From Auschwitz-Birkenau, they were transferred to the Gross Rosen and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps in Germany during the dying months of the war. Emaciated to the bone and on the verge of death, they were liberated by the British army in April 1945, less than a month before Germany’s unconditional surrender.

Like most Polish Holocaust survivors, they had no desire to be repatriated to Poland, 90 percent of whose 3.3 million Jewish citizens were obliterated in six years. They stayed in Germany — which was divided into U.S., British, French and Soviet occupation zones — until they could leave for greener pastures.

To the best of my knowledge, they spent the next three years in two displaced persons camps — Mitterfelden, which had been a German Air Force base, and Bad Reichenhall, an attractive spa town in the foothills of the snow-capped Bavarian Alps. It was there, in a clinic at 8 Maximillianstrasse which has since been converted into a three-story beige apartment building, where I was born in the summer of 1946.

I visited Bad Reichenhall in 1977 and then again in the mid-1990s. Situated in a scenic finger of Germany that thrusts into Austria, it is close to Salzburg and Adolf Hitler’s Eagle Nest vacation cottage, which was bombed by Allied aircraft in 1945.

I was impressed by Bad Reichenhall’s picturesque beauty and charm and its array of elegant cafes and shops, but I felt like an interloper there. During my trip, I acquired a copy of my birth certificate at the municipal building, the clerk taking less than five minutes to find it.

My parents, who had known each other in Lodz, met and married at a DP camp, like so many other survivors who longed for companionship and peace of mind after the catastrophic events of the previous years. They were unsure where they wanted to live in the future, but they were certain it could be neither Germany nor Poland.

As they mulled the possibilities, Samuel Bronfman, a wealthy Montreal businessman and the president of the Canadian Jewish Congress, finagled a meeting with Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King in 1947.

Bronfman told King that manpower shortages in the garment industry, centered in Montreal, Toronto and Winnipeg, could be alleviated if skilled Jewish craftsman in displaced persons camps in Germany were permitted to settle in Canada.

Given Canada’s abysmal record with respect to Jewish immigration from 1933 to 1945, when only about five thousand Jewish refugees were admitted into the country, King was noncommittal.

Cothing manufacturers, union bosses and Jewish community leaders launched a coordinated campaign to convince the government that the fate of the garment industry and the vitality of the economy hinged on the importation of Jewish tailors from displaced persons camps.

A Jewish delegation was dispatched to Ottawa to request the admittance of 2,000 workers and their families. The delegates promised officials that the costs of selecting, transporting and settling the new arrivals would be borne by the garment industry. In fact, the expenditures would be shared by employers, the Canadian Jewish Congress and the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society.

In October 1947, the admission of 2,136 tailors was officially approved by order-in-council 2180, subject to immigration, security and health screenings. Selected from among 38,000 mostly Jewish garment workers within a pool of 240,000 displaced persons, 90 percent of the new arrivals would be Jewish.

They had been chosen by a five-man commission which visited the displaced persons camps: Max Enkin, the president of Cambridge Clothes and of the National Council of Clothing Manufacturers; Samuel Herbst, the business manager of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, Samuel Posluns, a member of the Cloak Manufacturers’ Association of Toronto, Bernard Shane, the treasurer of the Jewish Labor Committee, and David Solomon, the executive director of the Manufacturers’ Council of the Ladies’ Coat and Suit Industry.

Enkin, who had been instrumental in the founding of the Jewish Vocational Services agency in Toronto, led the team. Matthew Ram, a young social worker from Montreal who had been hired by the Canadian Jewish Congress to work with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in the camps, kept the project on track.

On the eve of their departure for Europe, they were informed that C.D. Howe, the minister of reconstruction and supply, objected to the preponderance of Jews in the program. On Howe’s instructions, Labor Minister Arthur MacNamara conveyed this message to the commission’s lawyers, J.J. Spector and Norman Genser, who were both shocked to hear such a bold articulation of the government’s aversion to Jewish immigrants.

Howe, meanwhile, relayed the same message to Enkin: “Under no circumstances could they proceed with this scheme if there were more than 50 percent Jews selected.”

The commission contemplated raising an outcry, but resigned itself to “half a loaf” rather than none.

With the addition of dependents, some 6,000 displaced persons eventually came to Canada under this project, with the first batch of Jewish tailors arriving at Halifax’s Pier 21 and Quebec City in January 1948.

My parents and I embarked on our voyage to Canada in the German port of Bremerhaven. Along with hundreds of other displaced persons, we boarded the S.D. Sturgis, a U.S. naval vessel named after Samuel Davis Sturgis, an American general who fought in the Mexican-American War, the Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Five hundred feet in length, the vessel was built in California in 1943 and acquired by the U.S. Navy in March of 1944. At first, it ferried combat troops to the European, Pacific and Middle East theatres of operation. Later, it carried civilian passengers. During its final years, it was cargo ship. Sold to a steel company in Taiwan, it was scrapped in 1980.

We arrived at Pier 21 in Halifax, I believe, on February 6. Camillien Houde was mayor of Montreal, Maurice Duplessis was premier of Quebec and Harry Truman was president of the United States. On this day, too, Barbara Ann Scott became the first Canadian to win a women’s figure skating Olympic gold medal, Frankie Carle’s Beg Your Pardon was the number one song in the United States, and The Snake Pit was the most popular Hollywood movie.

On Thursday, February 12, we reached our destination in Montreal as our train pulled into Windsor Station under a plume of smoke. I have vivid memories of stepping into a cavernous and noisy railway station, but I may be conflating it with another station.

On the day of our arrival, the main stories on the front page of The Gazette, Montreal’s second biggest daily English-language daily newspaper, consisted of a hodgepodge of news: a massive fire in Toronto, a Bank of Canada economic forecast, a Soviet accusation that the West had backed Hitler, the high price of food, and a wage freeze in Britain.

We were met at the station by social workers, and they directed us to a modest apartment at 3679 St. Famille Street, a few blocks from St. Lawrence (Laurent) Boulevard, in the heart of a heavily-populated Jewish district.

My father’s first job in Canada, at Towne Cloak on 423 Major Street, gave us a foothold in our new surroundings. Not long afterwards, he obtained a better position at Stein & Gerson, on Peel Street, that he kept for the next two decades.

Within a year of our arrival, my mother gave birth to her second child, Marilyn. In 1954, she had another girl, Shirley, rounding out our family.

During our early years in Montreal, we gradually moved up in terms of housing, graduating from a basic street-level cold-water float on St. Urbain Street to a succession of new duplexes on Dunford Palace, Bedford Road and Lockwood Avenue with all the modern conveniences.

My parents worked hard and long and scrimped and saved to provide us with the middle-class lifestyle to which we aspired and became accustomed. They certainly passed on their work ethic to me.

Even at the best of times, they were torn by memories of the Holocaust, which had upended their lives, shattered their assumptions about the human race, and destroyed their families. Having been profoundly affected by their bitter fate, I count myself as something of a survivor in spirit.

More Jewish refugees from Europe landed in Montreal shortly after my parents’ arrival, turning this cosmopolitan city into a hub of Holocaust survivors. Henry Srebrnik, my oldest friend, hails from one of these families. He and his parents, Edward and Esther, turned up in Montreal in the summer of 1948. From the early 1960s onward, they were our neighbors just around the corner in the suburb of Cote St. Luc.

It is hard to believe that 75 years have elapsed since our arrival in Canada, a country to which I will always be appreciative and grateful. Canada gave my late parents a new lease on life, a compelling reason for living, and a steadfast belief in life’s infinite possibilities.