Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966) was the apostle of modern Islamic fundamentalism, arguably the most influential advocate of jihad in the 20th century.

Qutb, an Egyptian and a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, influenced followers by virtue of his belief that the greatest threat to Islam originated not from European colonialism or Zionism but from corrupt, venal and westernized Muslim rulers wallowing in jahiliyya, or ignorance. In his view, the Muslim masses were duty bound to overthrow secular regimes and replace them with governments loyal to the tenets of Shariah law.

Qutb’s disdain of the ossified political order in the Arab world was a two-edged sword, endearing him to Arabs clamouring for meaningful change and a theocratic state but enraging the Arab elite of princes, presidents and prime ministers who upheld the status quo and regarded his ideas with suspicion, loathing and fear.

The late spiritual leader of Al Qaeda, Osama bin Laden, recognized Qutb’s role as an important progenitor of Islamic radicalism, and bin Laden’s successor, the Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahiri, congratulated him for having “fanned the fire of Islamic revolution against the enemies of Islam at home and abroad.”

Indeed, as John Calvert observes in Sayyid Qutub and the Origins of Radical Islamism (Columbia University Press), a thorough account of his life, a consensus has emerged that the road to the Arab terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 in the United States can ultimately be traced back to this ideologue. Calvert, a professor of history at Creighton University in Nebraska and an expert in Islamic politics, writes, “One cannot deny Qutb’s contribution to the contemporary tide of global jihad.”

Interestingly enough, Qutb was late in coming to this hardline position, having begun his career in Islamic politics as a reformer and having switched to radicalism when Egypt attempted to suppress the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1950s.

Born in Musha, a village of brick and adobe dwellings in Upper Egypt’s Asyut province, he was the son of a conservative landowner. An elementary school teacher for seven years, Qutb became an administrator in the ministry of education, based in the Cairo suburb of Helwan.

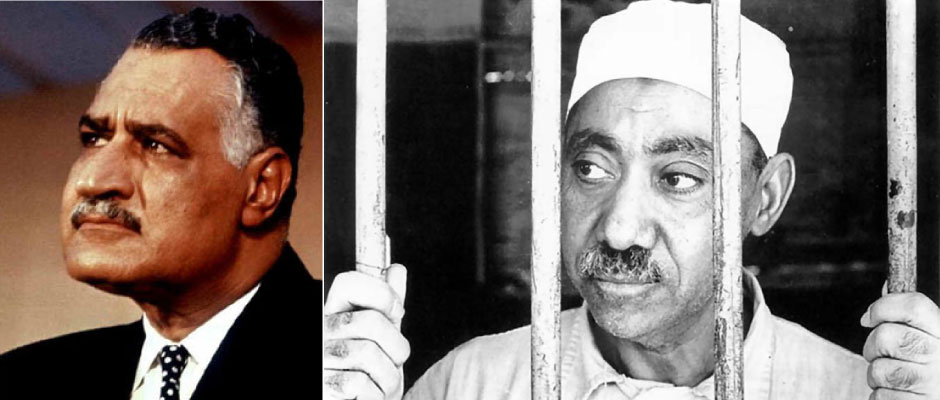

As Calvert notes, Qutb’s life unfolded against the backdrop of turbulence: the British imperial era, the advent of Egyptian nationalism and the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser. During this tumultuous era, Qutb belonged to the mainstream nationalist Wafd party, which dominated the political scene in Egypt until Nasser came along.

Eventually, Qutb grew critical of the Wafd, taking it to task for failing to resolve Egypt’s unequal colonial relationship with Britain, close the gap between rich and poor and confront the Zionist movement in Palestine.

To Qutb, the struggle of the Palestinian Arabs to uproot Zionism was a worthy cause. Deeply humiliated by Egypt’s defeat in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Qutb blamed Britain and the United States for their complicity in the outcome.

Qutb, however, was impressed by the violent tactics of the Irgun Zvi Leumi, an extremist Zionist militia that opposed the British mandate in Palestine by means of sabotage and assassination. He believed that Arabs in general and Egyptians in particular should emulate the Irgun in ridding the Middle East of foreign influence and control.

Qutb regarded Jews, both in Egypt and abroad, as enemies of Islam. Fond of quoting from a Quranic verse stating that “one segment of the People of the Book shall lead you astray,” he claimed that Jews from medieval times onward were untrustworthy, having been engaged in a battle to undermine Islam and denigrate the Prophet Mohammed.

Bringing his thesis up to date, he accused Jews of being the brains behind such ills as Freudian psychology and Marxist socialism. In short, he contended that Jews could only be tamed and contained if they agreed to convert to Islam or place themselves under the “protection” of benevolent Muslim rule.

Qutb’s Islamist predilections were reinforced by a two-year sojourn in the United States in the early 1950s on behalf of the ministry of education for further studies in educational administration. Appalled by the liberties and racism of American society, he categorized the United States as an oppressor of peoples and a polluter of universal standards of morality.

Upon his return to Egypt, Qutb, a lifelong bachelor, continued to agitate for change and renewal. Having left the Wafd party, he turned himself into an independent Islamic thinker, calling for an Islamic state in Egypt.

Initially, Qutb supported the military coup against the monarchy, working as a cultural advisor for the Revolutionary Command Council. The junta’s emerging reformist program had much in common with his own demands for social justice and national independence, Calvert writes. But when it became clear to him that Nasser and his fellow Free Officers had no intention of converting Egypt into a Sharia state, he joined the Muslim Brotherhood, to which he felt a strong emotional connection, and wrote for its publications.

A poet by avocation, Qutb was a published writer, having written such books as Social Justice in Islam, The Battle Between Islam and Capitalism and the first volume of his magnum opus, In the Shade of the Quran.

Qutb had boundless faith in the Muslim Brotherhood, saying it was the only organization capable of challenging Nasser and the enemies of Islam.

“No other movement,” he wrote, “can stand up to the Zionists and the colonialist Crusaders.”

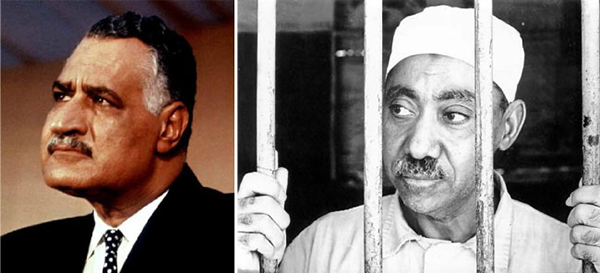

Three months after a member of the Muslim Brotherhood tried to assassinate Nasser, Qutb was arrested, charged with “anti-government activity.” In July 1955, he was sentenced to 15 years’ hard labour. He spent days and nights in a filthy cell, usually subsisting on a meager diet of lentils, rice and beans, but he was allowed to work on his books.

While in prison, he met communists as well as Egyptian Jews, who had been jailed for their participation in the Lavon affair, Israel’s crude attempt in the mid- 1950s to undermine Nasser’s regime.

Qutb was released from prison in 1964 thanks to the intervention of Iraq’s new president, who admired his writing. But he was rearrested a year later, along with 42 other members of the Muslim Brotherhood, after being accused of subversion, terrorism and sedition.

Sentenced to die on the gallows in August 1966, he exulted in his martyrdom. Despite appeals for clemency from Muslim clerics, he was hanged, his corpse interred in an unmarked grave.

Nearly 50 years on, the Muslim Brotherhood, which briefly ruled Egypt until Mohamed Morsi’s ouster in July, has a “skittish” attitude toward Qutb, “preferring to focus on his solid contributions to Islamic thought rather than his contributions to radicalism,” Calvert writes.

But Iran has no such qualms. In 1984, five years after the Islamic revolution deposed the pro-western Pahlavi monarchy, Iran issued a postage stamp in his honour portraying him behind bars at his 1966 trial.