Zosa Szajkowski was one of the strangest, most tragic figures in the annals of academia.

A devoted collector of French Judaica and a pioneer in the field of French Jewish history, he moonlighted as a thief, stealing priceless documents from state archives, synagogues and private Jewish libraries and selling them to institutions such as Columbia University, Yeshiva University and Brandeis University, where they still remain.

To Lisa Moses Leff, an associate professor of history at the American University in Washington, D.C., he left an ambivalent legacy.

“By stealing what interested him, Szajkowski created holes in French archives and new holdings in American and Israeli ones,” she writes in The Archive Thief: The Man Who Salvaged French Jewish History in the Wake of the Holocaust (Oxford University Press). “What’s more, in France, the disappearances led horrified French archivists to catalogue, for the first time, the collections from which Szajkowski had taken materials, thereby making those particular collections accessible in a new way. In the United States, the acquisitions of these documents created entire new collections based on his interests.”

Leff, in this deeply researched and intriguing book, draws a nuanced portrait of a scholar who turned to crime to preserve his status as a historian of modern Jewish history. From 1946 until his death in 1978, he worked as an archivist and research associate for the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City. But since he never received more than a modest salary, and could not obtain a university teaching position because his formal education had ended in high school, he resorted to theft to nurture his career and support himself and his family.

From 1940 to 1961, he acquired tens of thousands of documents about Jews in France and brought them to New York City. After using them for his scholarly articles, which appeared in respected journals, he sold them to American and Israeli research libraries and archives.

His method was crude but effective. He surreptitiously ripped pages out of bound volumes and carefully slid them into his briefcase. For years, no one suspected him because he was so well known to archivists.

But on April 13, 1961, he was caught red-handed taking rare documents from the city archive in Strasbourg, France. The archivist, Philippe Dollinger, treated him with kid gloves, assuming he was a scholar “impassioned by his research.” Instead of reporting him to the police immediately, Dollinger demanded a written confession, the return of the stolen documents and a donation to his archive, thereby giving Szajkowski ample time to flee before he could be arrested.

Two years later, however, he was convicted of theft in absentia and sentenced to three years in prison and slapped with a 5,000-franc fine. He never returned to France in the wake of his conviction, Leff believes.

Yet, as she points out, Szajkowski had previously come under suspicion as a thief. In 1948, and again in the 1950s, he was suspected of having removed pages from the library of the Alliance Israelite Universelle in Paris and the Alsace-Lorraine archive in Strasbourg.

These incidents did not spell the end of his career as a collector, dealer or historian. Always resourceful, he found new buyers for French Jewish documents outside of France, and shifted the focus of his scholarship from France to the United States.

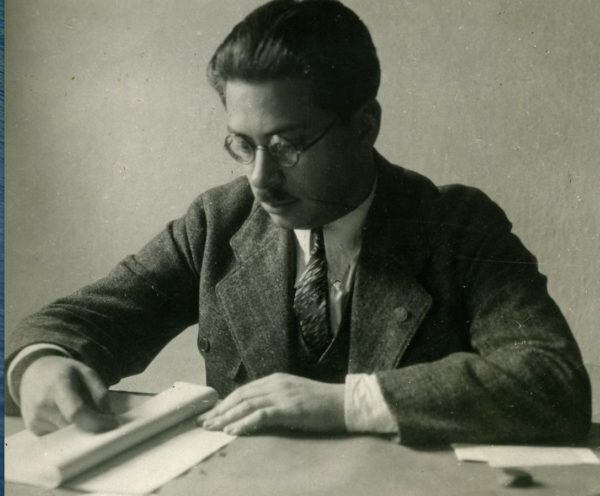

Born in the Polish shtetl of Zareby-Koscielne in 1911, he left Poland at the age of 16 to join his older siblings — Zilke, Zalmen and Dina — in Paris. Leff claims his love of history and “documentary remnants of the Jewish past” was ignited in the mid-1930s by a Ukrainian Jewish couple, Elias and Rebecca Tcherikower, who would be his mentors. Collectors of Judaica and members of YIVO, they fled Ukraine after a series of pogroms and lived in Berlin before moving to Paris. Szajkowski regarded them as surrogate parents.

When he first met them, he was working as a journalist for the Naye Prese, a Yiddish-language Communist daily read by Jewish immigrants. A Communist before emigrating from Poland, he left the party in 1938 or 1939, rejecting political ideology altogether. “Scholarship itself became his new faith, different in content but not in passion from his earlier beliefs,” Leff observes.

Szajkowski, who went by the pen name of Yehoshua “Shayke” Frydman, abandoned journalism to hone his craft as a historian. At his own expense, he published his first book in Yiddish: Studies on the History of the Immigrant Jewish Settlement in France.

In the autumn of 1939, as the Wehrmacht consolidated its grip on Poland, he joined the French army. Thanks to YIVO, he managed to obtain a U.S. visa, along with about 2,000 other writers, artists and anti-Nazi activists whose lives were in jeopardy. Before leaving France, he collected documents of historical value in the town of Carpentras. He arrived in New York City in September 1941 after an unpleasant six-week voyage on a crowded banana freighter with no amenities.

YIVO hired him to work on the documents he had sent to the United States. He worked with some of YIVO’s finest scholars, including Max Weinreich and Yudl Mark.

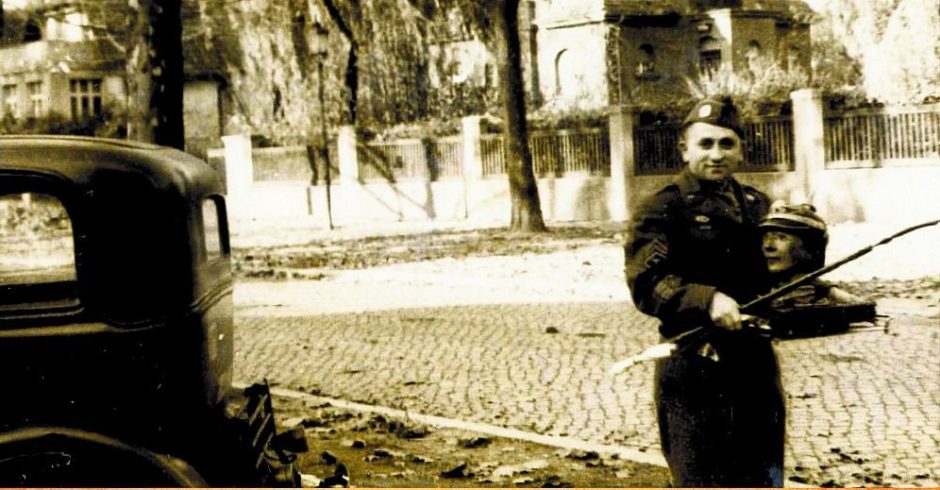

Szajkowski joined the U.S. army at the end of 1942, hoping that his path to American citizenship would be speeded up and that his service would contribute to Germany’s defeat. He was given training in military intelligence and interpreting.

Toward the close of the war, he learned that his family in Poland had been murdered during the Holocaust.

Finding himself in Germany in 1945, he scoured the archives of Nazi ministries, stumbling upon the papers of perpetrators. He sent the contents to YIVO. His actions were contrary to U.S. army regulations, but he had no trouble forwarding his trove of documents to the United States. YIVO appreciated his work, and its newsletter cast him in glowing colors.

In 1946, YIVO hired him and put him in charge of gathering materials from Europe. Szajkowski also wrote catalogues for YIVO exhibitions and articles for its scholarly journal. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, most of his articles concerned French Jewish social and economic history, all based on original archival research in France. Between 1946 and 1961, he published about 100 journal articles. His six scholarly books were self-published. As he established his reputation, he formed close ties with Salo Baron, one of the leading figures in Jewish studies in the United States.

Beyond teaching a course on archival sources in modern Jewish history at Brandeis University in 1973 and 1974 and giving guest lectures about the Holocaust at Hampshire College in the same years, he never taught.

On the eve of one of his trips to Europe, his boss warned him not to take anything of questionable provenance. Stung by the implicit rebuke of his methods, he resigned, determined to make it as an independent scholar. But he was soon back at YIVO again.

Szajkowski’s downfall unfolded quickly.

On September 26, 1978, he was arrested outside the New York Public Library in a police sting operation. “Szajkowski was stealing again, this time from a collection of pamphlets and ephemera, some of which were exceedingly rare … Szajkowski had been working his way through the collection for some time …”

Shamed, disgraced and exposed as a thief yet again, he committed suicide, drowning himself in a hotel bathtub on September 26.

In Leff’s judgment, Szajkowski’s decision to lead a life of crime, while pursuing a career in academia, was based on a rational calculation. In a reference to his thefts, she writes, “They provided him with the documents he needed for his research and the money he needed to devote himself to it.”

She is critical of the hypocrisy displayed by the Jewish scholarly establishment toward him. It appreciated the archival materials he provided and the scholarship he produced, yet it often looked the other way when confronted by evidence of his misdeeds.