The first feature-length movie about the French mime Marcel Marceau, The Art of Silence, will be screened at the Hot Docs documentary film festival in Toronto, which runs from April 28 to May 8. It was written and directed by the Swiss filmmaker Maurizius Staerkle Drux.

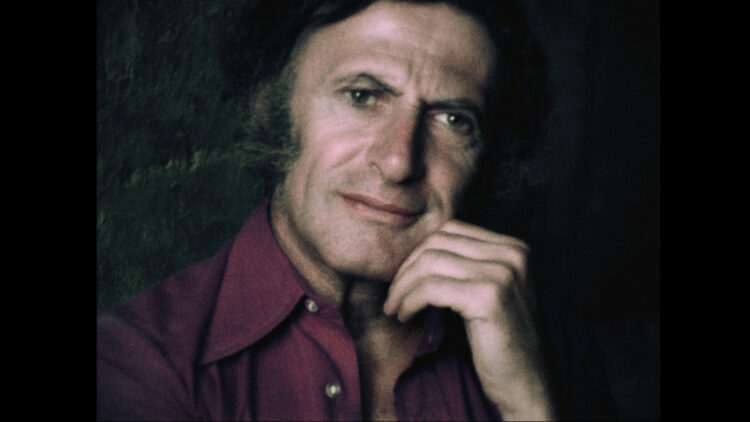

Marceau (1923-2007) subscribed to the theory that he did not need the adornment of sound to interact with his audience. The endearing stage character he portrayed, Bip, was a clown who communicated through vivid gestures and facial expressions. These were tricks he learned from the great British comedian Charlie Chaplin, his boyhood idol. His face smeared with eerie white makeup, he wore a striped jersey, white pants and a battered hat topped with a red flower.

He was invariably on the road, working 300 days a year in France and abroad. Since he was rarely at home, he was almost like a stranger to his family.

“He remains a mystery to me,” admits one of his grown daughters. “I hardly knew him,” says his 16-year-old grandson, Louis, who aspires to be a dancer.

To his legion of fans, Marceau was a substantive and alluring figure, a master of pantomime who could convey a feeling or an idea with a flick of his fingers, a movement of his hands or a roll of his eyes.

“I can be anything,” says Marceau. “The wind, god.”

Although he vented his emotions freely in performance mode, he repressed a deep-seated reservoir of sorrow and anguish, Drux suggests in this impassioned film.

Marceau, the son of Ukrainian and Polish Jewish immigrants, was born in Strasbourg. He was 17 years old when Germany occupied France and a collaborationist Vichy regime passed its first antisemitic law reducing Jews to second-class citizenship. Marceau, whose original surname was Mangel, felt the sting of antisemitism.

In 1944, just months before France was liberated by the Allies, Marceau’s father, a kosher butcher, was rounded up and sent by train to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland. There he was gassed, along with Jews from the four corners of Europe.

His mother eluded the Nazi onslaught, but Drux offers no explanation for her survival.

Marceau joined the resistance movement. And as his cousin recounts, he created fake identity papers for several hundred Jewish children and accompanied them by rail to neutral Switzerland. En route, he entertained them, displaying his talent as a mime.

Pursuing a career in postwar France, Marceau turned Bip into a character who dreamed of a better world. “He was a very gentle person, a pacifist,” recalls one of his daughters.

Since he was always worried that pantomime would die with his death, he opened a studio where aspiring mimes could learn the craft. One of his students, Bob Mermin, is grateful for what he learned. “He taught me how to move through the world,” he says.

The pop singer Michael Jackson was also influenced by Marceau, having developed his “moon walk” routine after watching him perform.

Marceau was a giant in his field, and Drux gives him due credit in this intricately-layered biopic.