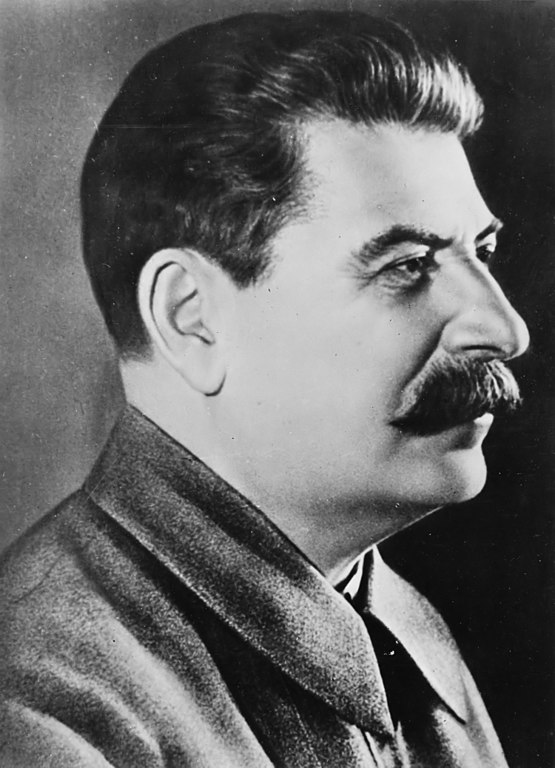

The notorious antisemitic campaign launched by Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union after World War II is chronicled in exacting and chilling detail in Guillaume Ribot’s superb French-language documentary, The Black Book, which will be screened online on June 3 at this year’s Toronto Jewish Film Festival.

Guillaume’s 92-minute film revolves around the Black Book, a volume that graphically exposed the antisemitic atrocities of Nazi Germany in the Soviet Union from 1941 to 1945.

Laboriously compiled by a group of Russian Jewish intellectuals loyal to the regime, it was suppressed during the communist era. Its dismal fate was a disturbing reflection of the suspicion and hostility to which Soviet Jews were subjected in the twilight of the Stalin era. It’s a story of terror and amnesia, as Guillaume correctly observes.

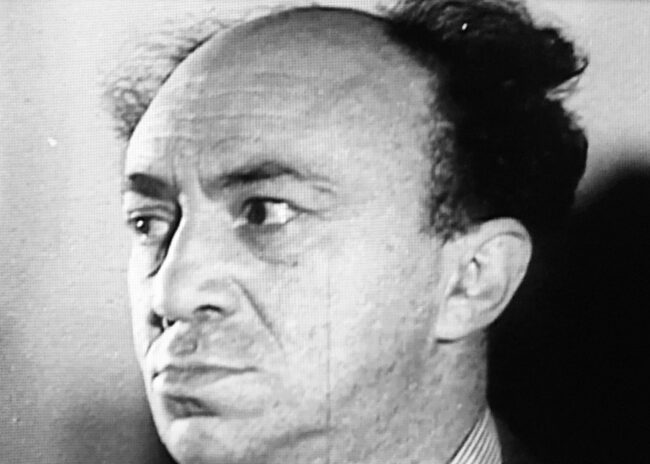

The towering figures in his film are Illya Ehrenburg, a journalist who instinctively understood what lay in store for European Jews after Adolf Hitler’s accession to power; Solomon Mikhoels, an actor on the Yiddish stgte and the director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater, and Vasily Grossman, an author and journalist who knew them both. All three, assimilated Jews, were members of the Communist Party.

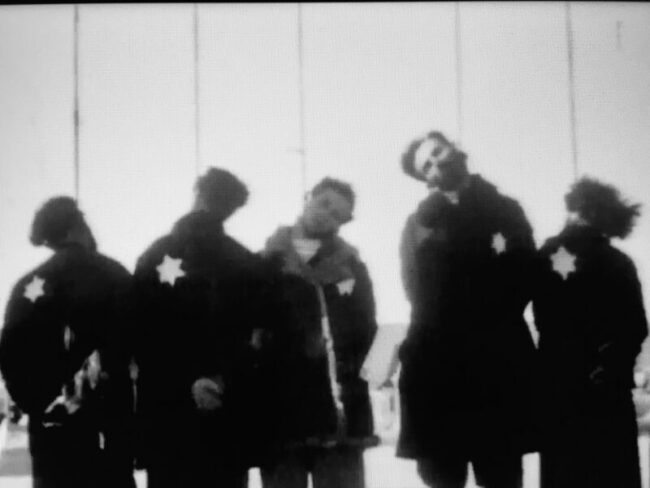

From the moment the German army invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, its five million Jews were imperilled. By the time the Wehrmacht had been defeated four years later, suffering 90 percent of its wartime casualties in the killing fields of the Soviet Union, 1.5 million Jews had been murdered by Nazi mobile killing squads, German soldiers and local collaborators.

As the war raged, Ehrenburg and Grossman wrote stirring news accounts of the fighting for Red Star, a mass-circulation Soviet army newspaper. All the while, Ehrenburg received hundreds of letters from soldiers on the front outlining systematic Nazi atrocities against Jewish civilians.

With the Germans advancing deep into the Soviet Union in the first 12 months of the conflict, Stalin created the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, appointing Mikhoels as its chairman. Its function was to rally international Jewish support for the Soviet war effort and to raise funds for the acquisition of weapons.

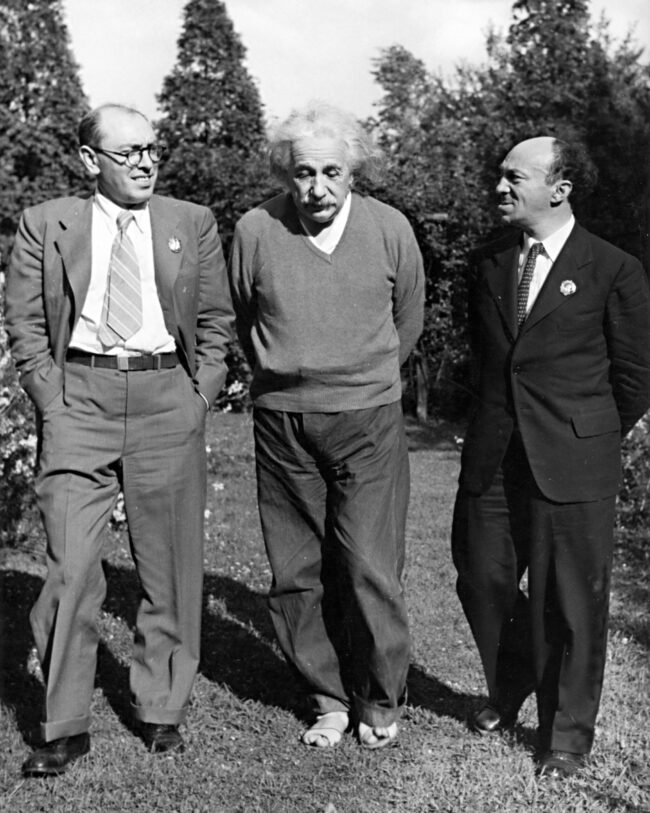

In July 1943, the Soviet regime sent a Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee delegation to the United States and Canada to inform Jewish communities of Nazi crimes. It was led by Mikhoels and the Yiddish poet Itzik Feffer. During one of their stopovers, the Nobel laureate Albert Einstein suggested that a “black book” should be published about these murderous rampages and that it should be used to prosecute Nazi war criminals.

Grossman, in the meantime, was shocked by reports that residents of Odessa had collaborated with the Germans and by rumors that Red Star employed too many Jews. In the Ukraine, where his dearly beloved mother lived, he was saddened to learn of the destruction of numerous Jewish communities.

Red Star, in an unmistakable sign of things to come, rejected his piece, Ukraine Without Jews. From this point forward, the Soviet media downplayed or ignored the mass murder of Soviet Jews. But Mikhoels, pushing ahead with his plan to publish a black book, asked Ehrenburg to assemble a task force to gather first-hand material for it. Ehrenburg’s friend, Grossman, joined the project.

Stalin did not voice objections, believing it could be useful in the postwar trials of Nazi criminals.

Travelling through Belarus and Poland, Grossman visited localities where Nazi crimes had occurred. He was one of the first journalists to visit the blasted ruins of Treblinka, which consumed the lives of 900,000 Jews. At the end of his eye-opening trip, he suffered a nervous breakdown.

In 1945, Mikhoels was advised by the Kremlin that if The Black Book was “good,” it would be published. To his immense disappointment, the manuscript was deemed “unfit.” The official explanation was that it dwelled unduly on Soviet collaborators and not sufficiently on German war criminals.

Deflated by the verdict, Ehrenburg and Grossman deleted the “offensive” passages, while Ehrenburg stopped working on the book altogether. Yet interestingly enough, the Soviet prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crimes trial drew on its information in his closing speech.

In 1946, the Kremlin decreed that the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was becoming “more and more nationalistic and Zionistic.” A year later, the Communist Party’s Propaganda Department slammed The Black Book, claiming it contained “grave political errors” and could not be published.

Succumbing to despair, Mikhoels concluded with a heavy heart that Jewish culture had no future in the Soviet Union. Shortly afterward, he was murdered by the KGB in Minsk on Stalin’s express order. Ever the arch cynic, Stalin organized an elaborate state funeral in Moscow for the fallen Jewish leader.

Stalin’s paranoia regarding Jews was stoked by the emergence of Israel as a sovereign state in 1948. Although the Soviet Union voted for the historic 1947 United Nations Palestine partition proposal, and became the first nation to recognize Israel on a de jure basis, Stalin accused the Jewish state of joining the “imperialistic” camp. His animus toward Israel, and Jews, was exacerbated when a large crowd of Soviet Jews in Moscow greeted Golda Meir, Israel’s first ambassador in Moscow, with adulation.

Convinced that Jews were plotting against the Soviet Union, Stalin closed Jewish newspapers, the Moscow State Jewish Theater and the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. He also accused Jews of conspiring to form an independent Jewish republic in Crimea. Amid this acrimonious atmosphere, The Black Book was condemned by the Kremlin as subversive and its proofs were confiscated.

In 1949, Pravda the organ of the Communist Party, launched a campaign labelling Jews as “cosmopolitans” and “vagrants without passports.”

Under intense pressure, Ehrenburg was corralled into leading a Soviet “peace” delegation abroad to refute accusations that the Soviet government was persecuting Jews.

Further indignities surfaced when Grossman’s new novel was rejected because its main character was Jewish and when all references to the Holocaust vanished from the Soviet media and official speeches.

What followed, in 1953, was still worse. On the heels of accusations that Jews were planning to kill the Soviet leadership in the infamous Doctors Plot, rumors emerged that Stalin intended to deport Soviet Jews to Siberia.

With Stalin’s death in the same year, the antisemitic campaign suddenly ground to a sudden halt. A period of liberalization set in, but in 1961, Grossman’s novel about the war, Life and Fate, was rejected by a state publishing house, and all his books were banned.

Ehrenburg tried one last time, before his death in 1967, to have The Black Book published, but he failed. It was not until the collapse of communism that this maligned but historically important document finally saw the light of day.