The 19th century German Jewish poet Heinrich Heine wrote, “Where books are burned, in the end people will be burned too.” What an insightful prophecy!

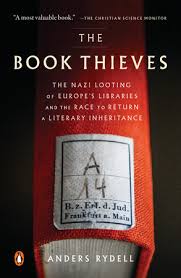

As the Holocaust — a Nazi genocidal project — unfolded throughout Europe during World War II, Germany engaged in the greatest book theft in history, ransacking private and public collections. “The targets of this plunder were the ideological enemies of the (Nazi) movement — Jews, Communists, Freemasons, Catholics, regime critics, Slavs and so on,” writes Anders Rydell in the paperback edition of The Book Thieves: The Nazi Looting of Europe’s Libraries and the Race to Return a Literary Inheritance (Penguin Books).

In their zeal to achieve victory, the Nazis not only strove to defeat their adversaries on the battlefield, but to eradicate their literary and cultural heritage by destroying their books, says Rydell, a Swedish journalist.

Even before the Nazi regime took to burning books and forcing writers into exile, Nazi thugs harassed writers such as Arnold Zweig and Thomas Mann, and a major Nazi newspaper published a blacklist of novelists whose books should be banned. A month after Adolf Hitler assumed power as chancellor in January 1933, President Paul von Hindenburg signed a bill imposing restrictions on printed publications. Three months later, the Federation of German Students proclaimed that German literature had to be “purified” and liberated from Jewish influence.

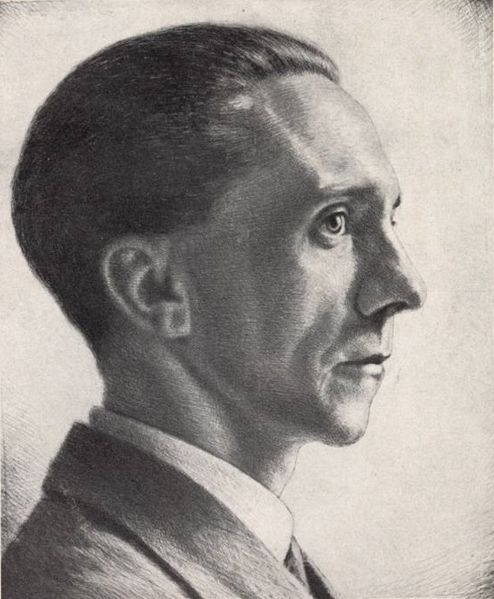

On May 10 of that fateful year, pro-Nazi students in Berlin marched toward the Opernplatz and proceeded to set fire to mounds of “undesirable” books in history’s most infamous book burning ceremony. Book burnings, hailed by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels as a critical turning point in Germany’s rebirth, spread to 90 cities and towns in Germany during that fateful summer.

“Purification through fire was an ancient ritual that appealed to the new regime,” says Rydell in his informative book.

Goebbels, emboldened by this manifestation of cultural barbarism, took complete control of the German book industry, which consisted of 2,500 publishers, and began monitoring 16,000 book dealers and second-hand book shops. In short order, Jews were ousted from the industry and Jewish-owned publishing houses were transferred to Christian owners.

As these events occurred, Hitler’s memoir/manifesto, Mein Kampf, enjoyed a print run of 850,000 copies in 1933 alone.

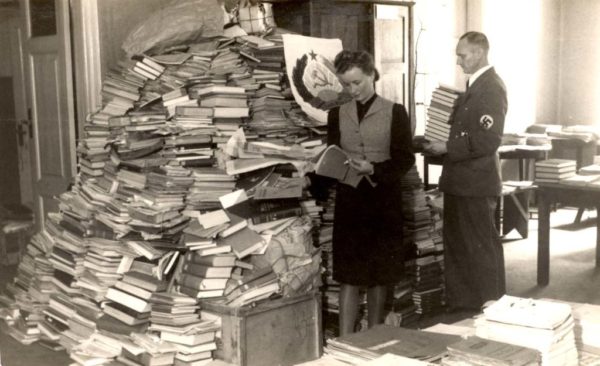

With the outbreak of war in 1939, the Nazis began pillaging books. Hardest hit by the plunderings were private collectors. As he explains, “Books in private collections were more difficult to identity because they had rarely been cataloged. If the books lacked owners’ marks, they were in practice absolutely impossible to trace back.”

Poland, the first country invaded by Germany during the war, was badly affected by the Nazi lust for books. Rydell estimates that 90 percent of public library and school collections were seized. In addition, 80 percent of Poland’s private and specialized libraries disappeared. By one estimate, 15 million of its 22 million books were lost, including the historical collection of the National Library.

“Only Polish Jews and their culture were hit harder,” he says. “One of the most valuable libraries that was lost was the great Talmudic library of the Jewish Theological Seminary in Lublin.” A Nazi who participated in the plundering said after the war, “For us it was a matter of special pride to destroy the Talmudic Academy … We threw out off the building the great Talmudic Library and carted it to market. There we set fire to the books. The fire lasted for 20 hours. The Jews of Lublin were assembled around and cried bitterly.”

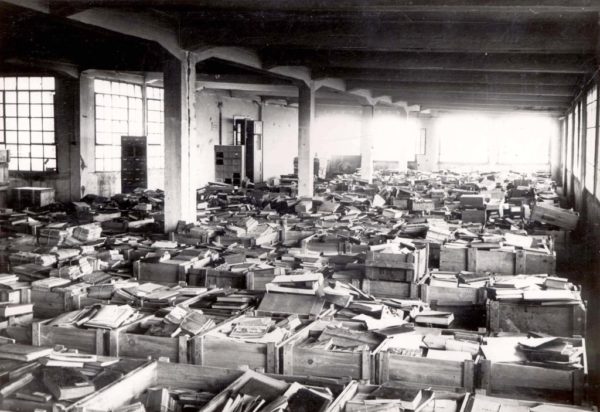

As many as 100 million books may have been destroyed or looted in the Soviet Union, Germany’s greatest ideological and military foe. “The Soviet regime had really cleared the way for the Nazi plunderers, because most of the collections had already been confiscated and nationalized, and Freemasons and similar organizations were banned,” says Rydell. “Much of the loot had either been sold off to the West or integrated into the public collections. The Nazis therefore focused on plundering the public institutions, which has the richest collections.”

Apart from plundering the collections of 532 synagogues, the Nazis plundered 1,670 Russian Orthodox churches and 237 Catholic churches.

In France, the Nazis confiscated several libraries belonging to the Rothschild family and books from the Turgenev Library, which had first editions of Voltaire, and the Polish Library, which had original manuscripts by Adam Mickiewicz. All in all, Rydell estimates, the Germans stole from 723 large libraries in France containing about 1.7 million books.

And in Rome, the Jewish community’s library was stripped of books and manuscripts from the 16th century that could not be found anywhere else. In the Greek city of Thessaloniki, 250 priceless Torah scrolls, along with a big collection of religious literature, were looted from synagogues.

The Nazis had a field day in Vilna, stealing objects from YIVO, which had one of the world’s largest collections of cultural and ethnographic artifacts relating to East European Jews.

As Rydell points out, the Soviet Union — and the United States — helped themselves to German collections. The Red Army confiscated more than 10 million books, while a U.S. Library of Congress delegation appropriated more than one million books.

According to Rydell, Germany is believed to have lost between one-third and one-half of its book collections due to plunder, bombing raids and fires.

In 1941, the Nazis opened an institution in Frankfurt dedicated to Jewish studies from an antisemitic perspective. Stocked with books plundered from Nazi-occupied Europe, it enabled researchers to produce skewed monographs about Jews. The Nazi Party newspaper, Volkischer Beobachter, boasted, “For the first time in history, Jewish studies without Jews.”

The shelves of libraries in Germany today are filled with looted books. While some have been returned to their rightful owners, others continue to gather dust and most likely will never be reunited with the people who once owned them.