Warner Bros., one of the major Hollywood movie studios, was founded on April 4 a century ago by four Jewish brothers whose immigrant family hailed from Poland.

The Warner siblings, Harry, Albert, Sam and Jack, worked together during the silent era and successfully transitioned into talkies, producing a succession of memorable films ranging from The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Big Sleep to Rebel Without A Cause and My Fair Lady.

Cass Warner Sperling’s documentary, The Brothers Warner, looks at these pioneers through nostalgic lens. Written and directed by Harry’s granddaughter, it was broadcast on the Turner Classic Movies channel recently.

A backward glance at Hollywood’s movie industry from almost its inception in the early 20th century, it is an amalgam of file footage, feature film clips and interviews with, among others, Betty Warner, Harry’s daughter; the actors Angie Dickinson and George Segal; the cinematographer/director Haskell Wexler; the producer Norman Lear; the executive Roy Disney Jr., and the historians Michael Birdwell and Nancy Snow. They offer viewers insider insights and interesting anecdotes.

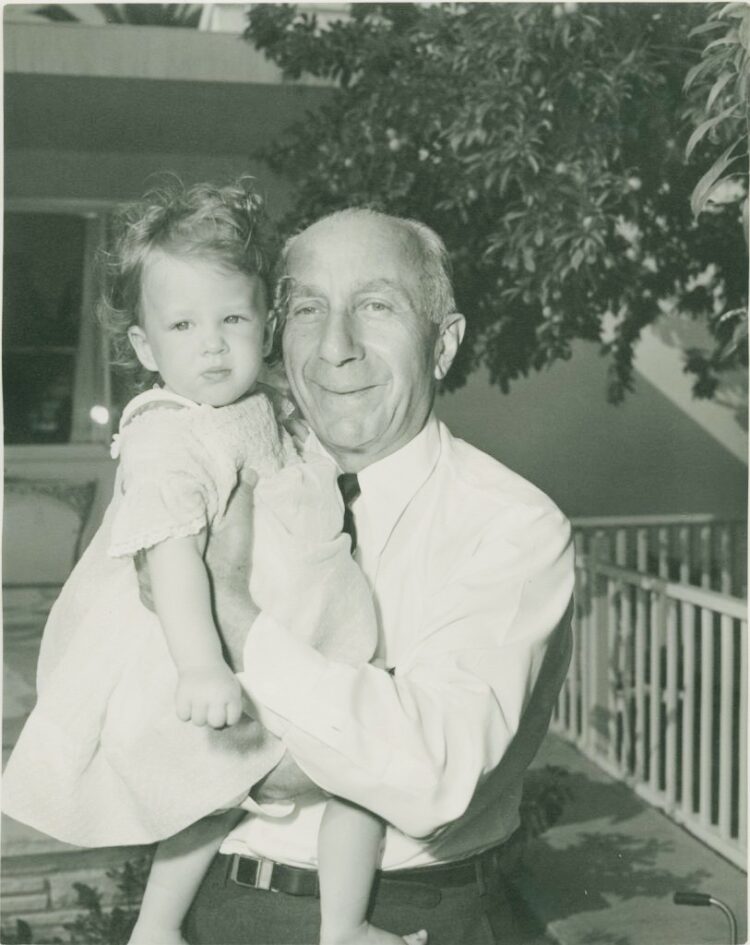

It should be noted that Sperling is favorably disposed toward her grandfather, Harry, a quiet, understated person. She is somewhat critical of Jack, a showboat, a playboy and a ladies’ man who was the egotistical face of Warner Bros. for many years.

The brothers, whose original surname was Wonskolaser, entered the fledgling film business by way of the nickelodeon, the precursor of the movie theater. They founded their studio in Los Angeles in the spring of 1923 after having churned out training films for the U.S. army.

Harry, the oldest brother, was the president. Albert was in charge of distribution. Sam was the producer. Jack was the chief of operations.

The Warners, inspired by Sam’s visionary outlook and technical expertise, were instrumental in bringing sound to the movies. In 1927, they released the first talkie, The Jazz Singer, starring the irrepressible Al Jolson. It was the most profitable movie in Hollywood’s history until Gone With the Wind in 1939.

Harry hoped that his talented son, Lewis, would succeed him as president. Much to Harry’s grief, Lewis died in 1931 at the tender age of 23, and Jack became the heir apparent.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, they commissioned hard-edged films with a social conscience: I’m A Fugitive From A Chain Gang, which led to prison reform; Black Legion, which railed against bigotry and piqued the ire of the Ku Klux Klan, and Black Fury, which was pro-union.

At Harry’s insistence, Warner Bros. was the first Hollywood studio to stop doing business with Nazi Germany. This principled position cost the Warners financially, since Germany was a lucrative market for American films.

In 1939, the Warners released Confessions of a Nazi Spy, Hollywood’s first anti-Nazi film. Starring the Romanian-born Jewish actor Edward G. Robinson, it irked the German government, which threatened to boycott U.S. movies.

Casablanca was also a statement against fascism. Starring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, it remains one of Hollywood’s finest wartime films.

Although the Warners did not downplay their Jewish heritage, they were careful not to insert the issue of antisemitism into their films. In The Life of Emile Zola, which charted the trials and tribulations of Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jewish army officer falsely accused of espionage, antisemitism was ignored and the word “Jew” never appeared in the dialogue, though it was seen fleetingly in a document.

Birdwell claims that the House Un-American Activities Committee, which was convened on Capitol Hill in 1947 to root out communists and communist influence in Hollywood, was tainted by antisemitism. Jack Warner cooperated effusively, comparing communists to insects.

The Warners, especially Harry and Jack, did not always work in harmony, and it was left to Albert to keep the peace in the family. It was irretrievably shattered in 1956 when Jack, in a Machiavellian maneuver, pushed Harry out of Warner Bros. Harry regarded Jack’s subterfuge as a great betrayal and never spoke to him again. Harry, broken-hearted, died two years later.

Jack stepped into Harry’s shoes and ran Warner Bros. like a fiefdom, but he, too, was edged out in a game of corporate intrigue. His last studio movie was Camelot.

Sperling speculates that the Warners may have lost control of the company due to family squabbles. “United they stand, divided they fall” might have been their motto.