A vast and incredibly beautiful preserve of mountains, forests, meadows, lakes and rivers northwest of New York City, the Catskills were the first great vacationland in the United States. Discovered in its pristine form by the British explorer Henry Hudson in 1609 and by tourists in its holiday mode about two centuries later, it was a hugely popular resort area by the close of the 19th century.

Jews began flocking in droves to the Catskills in the early 20th century, greatly accelerating its growth. Grossinger’s, one of the the first major hotels to cater to a Jewish clientele, competed with the Concord, Brown’s, Kutscher’s and the Nevele, among others. With the passage of time, the Catskills became known as the Borscht Belt and the Sour Cream Alps.

To Jews that bygone era, it was Disney Land writ large.

In The Catskills: Its History And How It Changed America (Alfred A. Knopf), Stephen M. Silverman and Raphael D. Silver examine its evolution from the 17th century onward. Well-written and lavishly illustrated, this coffee-table volume is both erudite and entertaining.

Originally inhabited by the native American Mohican Indians, the Catskills were penetrated by Hudson on a voyage upriver from Manhattan. A Dutch settlement, later renamed Albany, was established to facilitate the lucrative fur trade.

The writer Washington Irving was enchanted by the Catskills, which attracted a legion of landscape painters. As he observed, “The interior of these mountains is in the highest degree wild and romantic; here are rocky precipices mantled with primeval forests; deep gorges walled in by beetling cliffs, with torrents tumbling as it were from the sky …”

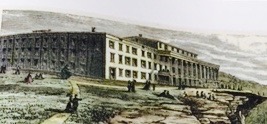

Benajah Douglas, the father of Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 presidential opponent Stephen Douglas, built a tavern and modest hotel in Ballson Springs in 1787. Its success led to the construction of the nearby Sans Souci Hotel, advertised as the largest hotel in the United States. It is where James Fenimore Cooper wrote his famous novel, The Last of the Mohicans.

Until the modern age, the Catskills could only be reached by way of primitive trails. They were supplanted by roads, known as turnpikes, linking towns and opening the remote interior to development. Railways speeded up that a process. During the 1870s and 1880s, yet more hotels opened.

The first Jewish person to live in the Catskills arrived in 1773. Less than a century later, 13 Jewish families, led by Moses Cohen, built an agriculture colony in the Ulster county town of Wawarsing. It was not until the late 1880s that the first Jews from the congested Lower East Side in New York City began arriving in the Catskills for vacations. They gravitated to boardinghouses, which had begun to be segregated into Christian and Jewish houses.

In 1877, the prominent Jewish banker Joseph Seligman arrived at The Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga Springs. He had spent the previous summer there, and it was a favorite of his contemporaries Andrew Carnegie and John Jacob Astor. He was denied a room on the orders of the new owner, Henry Hilton, who decreed that “no Israelites should be permitted to stop at this hotel.”

Seligman, a close friend of U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, fired off an indignant letter to Hilton that was picked by by a local newspaper. But the infamous incident triggered retrenchment rather than outrage. Hotels and boardinghouses stubbornly clung to their discriminatory policy, placing ads in newspapers that read, “No Hebrews Need Apply” and “Jews and Dogs Are Not Welcome.”

Responding to this blatant antisemitism, “strictly kosher” and Hebrew only” hotels, boardinghouses, kuchalayns (Yiddish for “cook yourself”) and bungalow colonies sprung up in rapid succession, particularly in Sullivan and Ulster counties.

Although the vast majority of hotels were Jewish, the Catskills were also home to Greek, Armenian, Hispanic, Italian, Irish, Chinese, Ukrainian and German hotels.

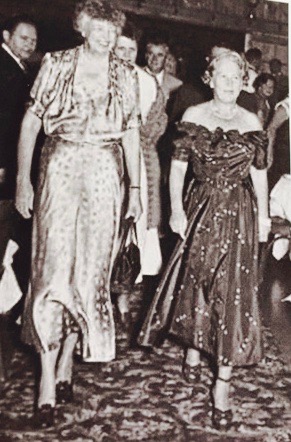

Grossinger’s, an iconic Jewish hotel, was founded in 1914 by a Jewish immigrant from Galicia. It would maintain its position as the gold standard for accommodations, service, recreational facilities and entertainment under one roof. Its matriarch, Jennie Grossinger, was the ultimate hostess, greeting guests as they checked in. As the authors write, “In the tradition of a matriarchy, where the Jewish mother was revered, women served as the trademark representatives of most large Catskills resorts.”

At these hotels, food was of primary importance.

“To understand the emphasis on food,” writes the scholar Johnathan Sarna, “one has to understand hunger. Immigrants had memories of hunger, and in the Catskills, the food seemed limitless. There was a sense that ‘too much was not enough.'” When someone asked the wife of a New York newspaper columnist how to lose weight at Grossinger’s, she replied, “Go home.”

Entertainment was also a high-priority item. Comedians like Jacky Mason and Mel Brooks launched their careers in the Catskills.

The good times lasted until the 1960s and 1970s, but the 1950s were the best decade in terms of profitability. The bungalow colonies were the first to go under, followed by the smaller hotels. The glitziest ones hung on the longest. The Concord outlived its rival, Grossinger’s, by a dozen years, only to die a slow, natural death in the late 1990s.

Their demise was due to a number of related reasons. “Air conditioning and the urban flight to the suburbs no longer made a summer escape to the mountains resorts a necessity,” explain Silverman and Silver. The 1964 Civil Rights Act ended the ugly era of the restricted hotel, and cheaper air travel abroad was the final nail in their coffin.

Grossinger’s, in 1993, was bought by a Japanese entrepreneur and was transformed. “Miso soup replaced borscht, and bacon was served with bagels at breakfast,” lamented an observer. The hotel soon foundered. As for Brown’s, it was sold at a foreclosure auction in 1998 and was subsequently converted into condominiums.

While they lasted, these resorts were magical places deeply embedded in the Jewish imagination.