It was, as author Lucy Adlington aptly observes, a “hideous anomaly.”

Tucked into a building at the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland was the Upper Tailoring Studio. Established by Hedwig Hoss, the camp commandant’s wife, and staffed mainly by European Jewish women who had been deported there, it catered exclusively to the wives of SS officers and guards and a clientele in Berlin.

These enslaved workers created beautiful garments for Germans who regarded Jews as subhumans unworthy of life. “For the dressmakers in the Auschwitz salon, sewing was a defence against gas chambers and ovens,” writes Adlington, a British clothes historian, in The Dressmakers of Auschwitz (Harper-Collins), which explores an intriguing, yet little known, footnote of the Holocaust.

To Adlington, this fashion salon encapsulated “qualities of privilege and indulgence, bound up with plunder, degradation and mass murder.” Certainly, the conjunction of fashion with genocide was probably unique in the annals of the Holocaust.

As Adlington notes in her finely-crafted book, women from the Nazi elite valued clothing, which could reinforce group pride and identity. Magda Goebbels, the wife of German Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, was known for her sartorial elegance. Eva Braun, Adolf Hitler’s mistress and short-lived wife, adored couture. Hoss was no different.

Ironically, the German fashion industry prior to the Nazi takeover was heavily reliant on Jewish capital, talent and connections. Roughly 80 percent of department stores and chain-store businesses were owned by German Jews. Almost half of the wholesale textile firms in Germany were run by Jews. And Jewish workers were heavily involved in the design, manufacture, distribution and selling of clothes.

“Berlin was an acclaimed center of women’s ready-to-wear apparel thanks to the energies and intelligence of Jewish entrepreneurs over a century of development,” writes Adlington.

Shortly after Hitler’s accession to power in 1933, his regime created the Federation of German-Aryan Manufacturers of the Clothing Industry, or ADEFA, whose sole purpose was to push Jews out of the market. “ADEFA publicity sought to ‘reassure’ German buyers — trade and public — that every single stage of a garment’s manufacture was untainted by Jewish hands,” she says.

ADEFA was dismantled about a month before Germany’s invasion of Poland, which led to the outbreak of World War II. By then, upwards of 7,000 Jewish businesses in the fashion industry had been looted, trashed or Aryanized, including a shop in Leipzig belonging to Hunya Volkmann, who was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau in the summer of 1943.

She would be one of the 25 seamstresses whom Hoss employed in the Upper Tailoring Studio, which was up and running in 1943. Its workers were German, Hungarian, Slovakian, Polish and French. Most were in their late teens or early twenties. The youngest was 14.

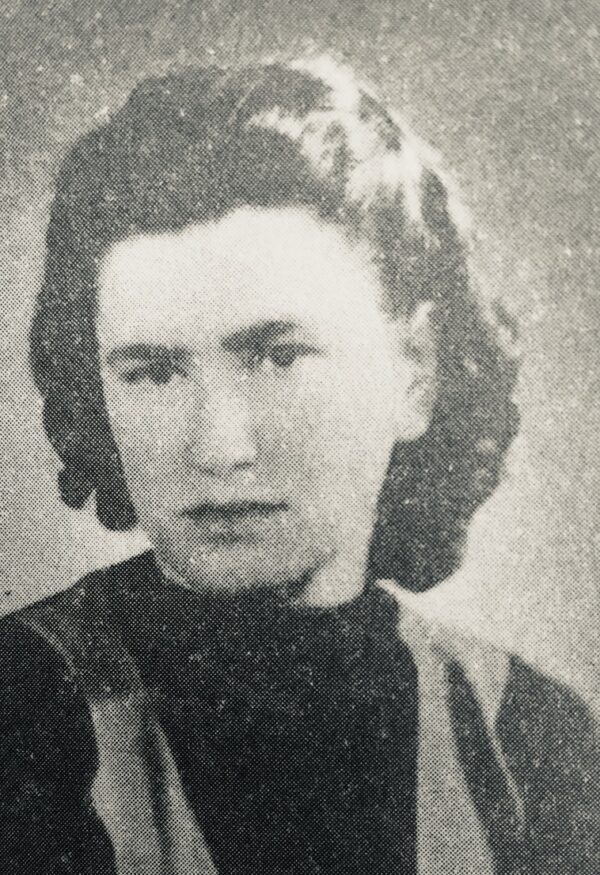

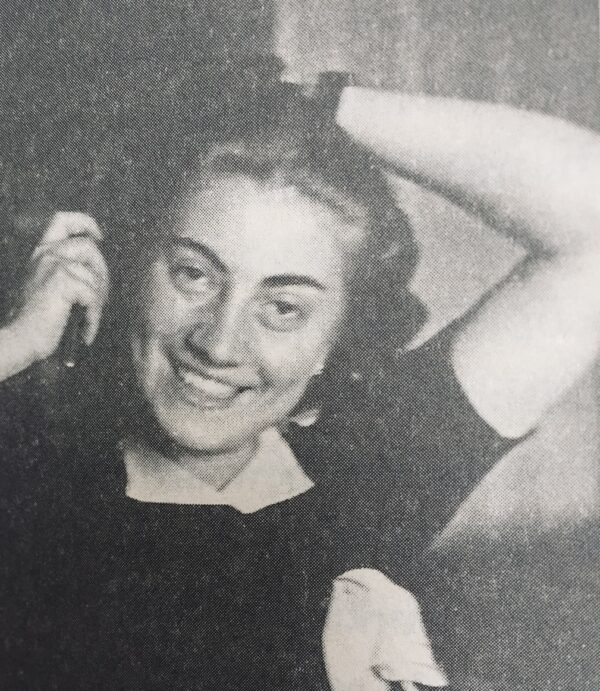

Among them were Irene Reichenberg, Marta Fuchs and Bracha Berkovic, all of whom were Jewish, and Alida Delasalle, a French Catholic.

At first, they were consigned to hard labor at Auschwitz-Birkenau, forced to dredge stagnant ponds, dig drainage ditches, fortify river banks and drain swamps. Then they stitched German army uniforms in a wooden building near the camp’s main entrance.

And finally, they worked for Hoss, who started the Upper Tailoring Studio after finding a skilled seamstress to refashion a collection of fur pieces into a coat. Marta Fuchs volunteered, and that was the beginning of the Upper Tailoring Studio, which was outfitted with modern equipment.

The second-hand clothes and fabrics Hoss acquired to alter into suitable outfits were plundered from Kanada, a gigantic warehouse containing the belongings of Jews who had been murdered almost immediately after arriving in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Although it was a murder factory that consumed the lives of 1.1 million Jews, Hoss pretended she inhabited an alternative universe. As Adlington points out, she treated guests to exquisite feasts in the cottage where she and her family lived. Among her guests were Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, and Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust, who described Hoss’ home as “homey and nice.”

Like all of the visitors, they could relax at picnics along a nearby river and pause at Solahutte, an SS resort in the vicinity where they could sunbathe, take walks in a meadow and pick blueberries.

Adlington describes Hoss as a typical Nazi wife who was no stranger to antisemitic rhetoric or Nazi concentration camps. Before Auschwitz-Birkenau, she had raised her children on the periphery of the Dachau and Sachsenhausen camps.

Under Marta Fuchs’ guidance, the seamstresses the Upper Tailoring Studio gained a reputation as elite professionals. “The core work for each seamstress was to produce a minimum of two custom-made dresses a week,” says Adlington. “The new clothes, with embroidery, smocking, piping and braiding, were designed to enhance, not to degrade or brutalize. It was an extraordinary flowering of beauty in a camp that was otherwise sloshing in shit.”

Hoss and her family left the camp in August 1944, when her husband was given a new posting in the Ravensbruck concentration camp in Germany. A month later, Allied aircraft accidentally struck Auschwitz-Birkenau, killing 15 SS men and injuring one seamstress. On January 17, 1945, with the Red Army advancing on the camp, the seamstresses were told their work was finished.

The Russians liberated the camp ten days later, and were astonished to find more than one million garments in Kanada.

Auschwitz-Birkenau was evacuated and female prisoners were pitilessly marched to Ravensbruck, where some were put to work at a nearby ammunition factory.

After the war, the survivors of the Upper Tailoring Studio went their separate ways, some to European cities and still others to Israel and the United States. Until their deaths, Adlington says, they had “to carry the knowledge that under extreme duress they had worked for the SS, that they had been coerced into clothing the commandant’s family, and that this had kept them from the gas chambers.”

Rudolf Hoss, the commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau, was hanged in 1947. His wife, living in western Germany during the postwar period, stayed true to her Nazi beliefs and, astoundingly enough, claimed that Jews had fabricated the myth of gas chambers in the camp. She died in 1989 while visiting her daughter in Washington, D.C.

The Upper Tailoring Studio was a grotesque blip on a monstrous Nazi screen, but it saved lives and enabled a few of its workers to return to normalcy after the Holocaust.