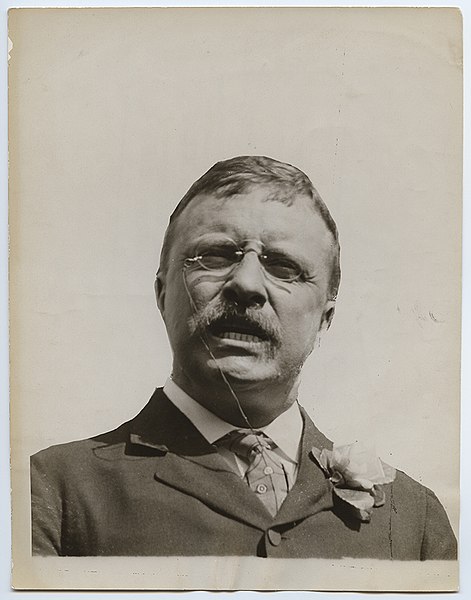

On the face of it, the eugenics movement in the United States seemed like a positive thing. Reaching its apex of popularity in the first third of the 20th century, it garnered the support of notable Americans such as Theodore Roosevelt, the former U.S. president; John Harvey Kellogg, the health reformer and inventor of the breakfast cereal Corn Flakes, and Margaret Sanger, the feminist and birth control advocate.

Dedicated to uplifting society by means of science, eugenics sought to improve the genetic makeup of the human race by weeding out the feeble-minded and eliminating undesirable traits in people. Its high-minded theorists claimed that heredity could be micro-managed by selective breeding and sterilization, which could reduce such maladies as corruption and crime and produce a far better world.

But there was a dark underside to eugenics, which was generally lauded by Americans of Anglo-Saxon and Nordic stock. In essence, eugenics promoted existing racial hierarchies and sought to prevent the influx of “foreigners” who could one day challenge the dominance of the white Christian ruling elite.

These enormously influential ideas, which morphed into racism and antisemitism, were deeply embedded in the United States by the 1920s, resulting in the passage of restrictive immigration laws that virtually closed the gates of Ellis Island in New York City. To eugenicists, the concept of the “melting pot” was nothing less than a disaster.

Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime in Germany adopted eugenics with zeal to marginalize, persecute and murder Jews before and during the Holocaust.

Its checkered saga unfolds in an intriguing documentary, The Eugenics Crusade, which will be broadcast by the PBS’ American Experience series on October 16 at 9 p.m. (check local listings).

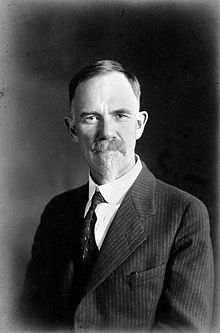

Charles B. Davenport, an American biologist and Harvard University zoology professor, was one of the central figures of the eugenics movement in the United States. After meeting Sir Francis Galton, a British statistician who believed in selective breeding and who coined the word eugenics, Davenport founded a special laboratory on Long Island in 1903 to unlock the mystery of evolution. If plants could be improved, he theorized, so could human beings.

Inspired by the Russian scientist Gregor Mendel, Davenport began his study by collecting family pedigrees. His long-term objective was to control human reproduction and thereby create a better race. This could be done by vastly reducing the number of misfits, degenerates, imbeciles and malcontents, all off whom were generally classified under the heading of “morons.” To a person like John Harvey Kellogg, eugenics made perfect sense.

Henry Goddard, an educator who called for intelligence testing, was also one of Davenport’s acolytes. So was Theodor Roosevelt, who declared that “degenerates” should not be permitted to bring children into the world. This was in keeping with a recommendation from the Eugenics Record Office — an outfit founded in 1910 — for mandatory sterilization. By one estimate, 15 million Americans from “socially inadequate classes” would have to undergo sterilization.

Davenport, who was of British, Dutch and Italian stock, came of age in an era when white Protestants felt threatened by the deluge of new immigrants pouring into the United States. These newcomers, consisting of Jews, Catholics, Slavs, southern Europeans and Asians, were deemed inferior in intelligence and culture by elitists like Madison Grant, the author of The Passing of the Great Race, a book that Hitler would read with glowing admiration.

Davenport himself wanted to keep out “cheaper races” from the United States. He and like-minded Americans spoke of the perils of unchecked immigration.

If the Anglo-Saxon and Nordic races were to retain their dominance, mass immigration would have to be drastically curbed. With this notion in mind, Congress passed legislation in 1921 to this end. Three years later, President Calvin Coolidge signed a law reducing immigration by a whopping 97 percent. Endorsed by progressives like Margaret Sanger, it would remain in force for the next four decades and would prevent Jewish refugees like Otto Frank — the father of the doomed Dutch-Jewish diarist Ann Frank — from obtaining a U.S. visa and fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe.

By the 1920s, eugenics was a household word in the United States, with more than 350 universities, including Harvard and the University of California, offering courses in eugenics.

In 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a ruling written by Oliver Wendell Holmes, sanctioned sterilization. Emboldened by it, a succession of states passed sterilization laws. By the 1970s, more than 60,000 American citizens had been sterilized. One of them, the socialite and heiress Ann Cooper Hewitt, sued her mother, who considered her feeble-minded.

Eugenics lost much of its credibility during the Depression, when Americans of all classes, races and religions were thrown out of work. It was now abundantly clear that genetics alone could not determine the destiny of a person, and that social, political and economic currents had to be taken into account as well. In short, eugenicists were increasingly regarded as cranks.

Eugenics was dealt a still more devastating blow when German concentration camps like Buchenwald and Dachau were liberated in 1945. It was clearer than ever that eugenics had morphed into racial hatred and genocide. Eugenics became a dirty word and the movement in the United States faded away, though mandatory sterilization in some states remained on the books until the 1970s.