In the wake of Hamas’ October 7 massacre in southern Israel, pro-Hamas Palestinian demonstrators and their supporters condemned Israel as a “colonial settler state.”

This false and outrageous claim runs counter to a glaringly inconvenient fact: Jews are indigenous to the Middle East and lived in the Land of Israel long before the emergence of Islam. Furthermore, Jews in this region coexisted with Arabs, sometimes uneasily, more than a thousand years prior to the rise of the Zionist movement.

These are the major points that Canadian filmmaker Martin Himel tries to convey in his newest documentary, The Forgotten Expulsion: Jews From Arab Lands, which will be presented on Vision TV in Toronto on Monday, October 7 at 9 p.m.

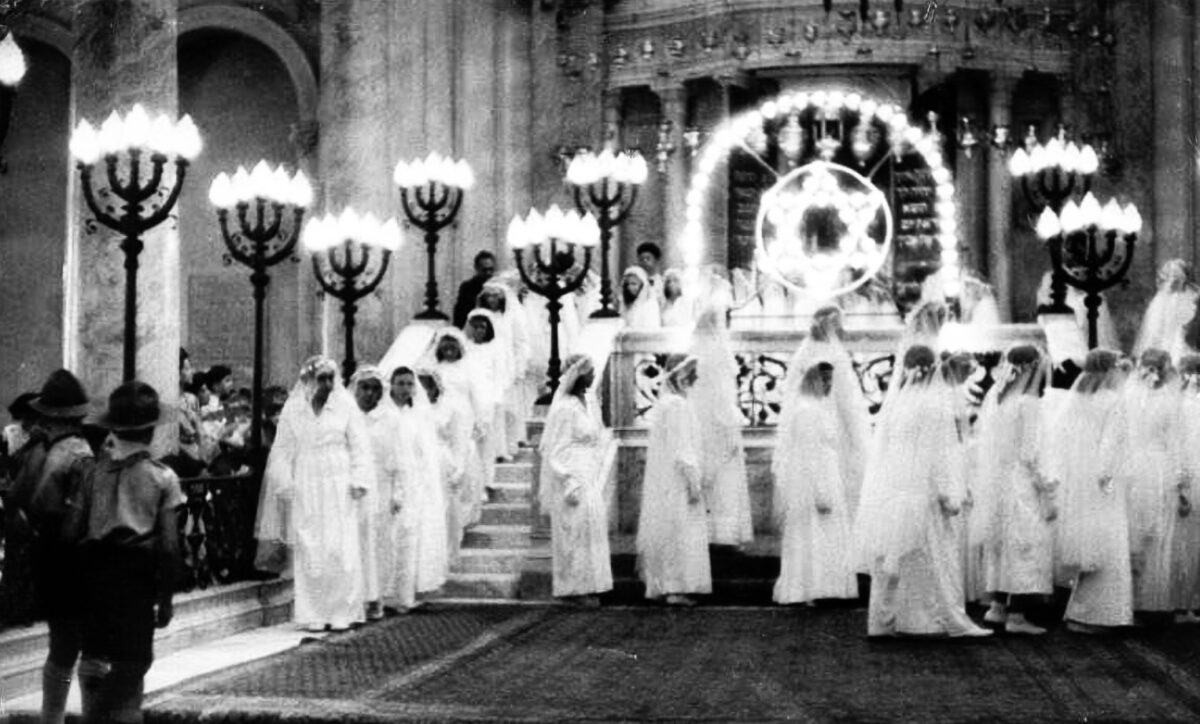

This 45-minute film is an amalgam of file footage, vintage photographs and on-camera interviews with people who hail from the Middle East or who have a special interest in this topic.

Among them are Avraham El Arar, the president of the Canadian Sephardi Association; Stanley Urman, the executive vice-president of Justice for Jews from Arab Countries; Shimon Ohayon, the director of the Dahan Center for Culture, Society and Education in the Sephardic Heritage at Bar Ilan University, and Henry Green, a professor of religious studies at the University of Miami.

Before the creation of Israel in 1948, the Middle East was home to about 800,000 Jews scattered in nations ranging from Egypt and Syria to Morocco and Iraq. Although Middle Eastern Jews were historically better off than European Jews, they labored under restrictions at various periods and were sometimes regarded as second-class citizens.

The birth of the modern Zionist movement, followed by the establishment of the Jewish state, created increasingly difficult and insurmountable problems for Jews in the Arab world. Demonized, marginalized, persecuted and hounded out of their native lands at around the same time that Arab refugees voluntarily or involuntarily left their homes in Palestine/Israel, they were never compensated for their losses.

In effect, they were the hapless victims of state orchestrated campaigns of ethnic cleansing that have been largely overlooked or forgotten.

Levana Zamir, an Egyptian Jew, recalls the good life she had in Cairo before local Jews came under suspicion and were conflated with Israelis. Eli Sardar, a Syrian Jew, talks about the mob that attacked a synagogue. Iraqi Jews recall a 1941 pogrom in Baghdad known as the farhud. Edwin Shuker, an Iraqi Jew who settled in Britain, visits Iraq on a sentimental journey after a long absence.

Judy Feld Carr, a Toronto activist, speaks of her role in helping some 3,000 Syrian Jews emigrate.

The Forgotten Expulsion underscores two important points. Middle Eastern Jews who lost their properties after 1948 should be compensated by Arab governments. Far from being interlopers, Jews are indigenous to Israel.

Given his time constraints, Himel only scratches the surface of these complex topics. Nonetheless, he manages to refute the nasty lies and half-truths about Israel that its enemies have been spreading with renewed ardor for nearly the past year.