How did the German people experience World War II? What did they think or know about their government’s plan to exterminate the Jews of Europe in the Holocaust?

These are among the key issues that Nicholas Stargardt deftly explores in his sweeping new book, The German War: A Nation Under Arms, 1939-1945, published by Basic Books. A professor of modern European history at Oxford University, he draws on personal diaries, military correspondence and court records to shed light on a devastating conflict that Nazi Germany willfully initiated.

When it invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Germany expected to fight a short, limited war of conquest. Adolf Hitler, the German chancellor, was confident that Poland’s allies, Britain and France, would not intervene. And German generals were relieved that the Soviet Union, Germany’s mortal ideological enemy, was now an ally thanks to an agreement Berlin and Moscow had recently signed to divide territorial spoils in Poland.

Although the outbreak of World War II was “deeply unpopular” in Germany, most Germans regarded it as a war of defence, forced upon them by “Allied machinations and Polish aggression,” writes Stargardt. The war was keenly felt even before the German army marched into Poland. Food rationing had already been introduced, and the war itself depressed the standard of living even further. By 1944, the war had forced the closure of luxury shops, restaurants and theatres.

Most of all, the war profoundly affected the parents, siblings and relatives of German soldiers. Within about a year of its eruption, 61,500 Wehrmacht troops had been killed in Poland, France, Holland, Denmark, Norway and Luxembourg. These fearsome casualties caused widespread pain and anguish.

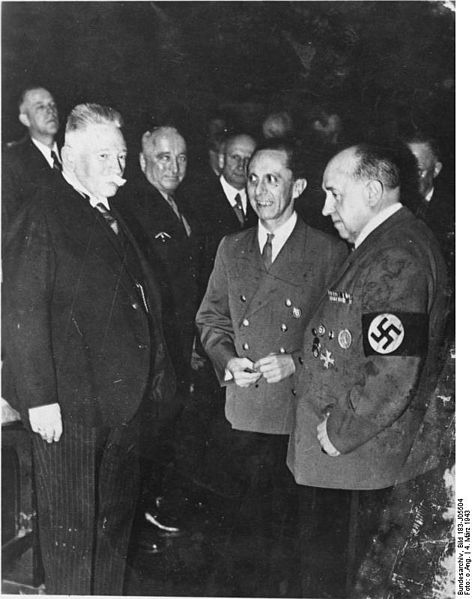

German Jews were initially allotted the same rations as everyone else, but in every other respect the 185,000 Jews who still remained in Germany in 1939, constituting 40 percent of the pre-war Jewish population, were a terribly maligned and persecuted minority. More than 200 antisemitic decrees had been issued since the Kristallnacht pogrom of 1938, and another 525 would come into effect between 1939 and 1941, the year Joseph Goebbels, the deeply antisemitic minister of propaganda, persuaded Hitler to introduce the dreaded yellow star. Goebbels hoped it would fan the flames of antisemitism, but instead it had the opposite effect. “People everywhere are showing sympathy for them (the Jews),” he complained. “The nation is … full of idiotic sentimentality.” As a result of this deficit, the government published a decree banning public displays of sympathy toward Jews.

German leaders regularly threatened to “solve” the Jewish question through genocide, writes Stargardt. On the eve of the war, Hitler had prophesied that the Jews would perish if they “started” a war. And in a speech in 1941, Goebbels declared, “We are now witnessing the fulfillment of this prophecy.” Jews, he disclosed, were being “gradually engulfed by the same extermination process that (they) had intended for us.” Hans Frank, the governor of occupied Poland, told his officials: “On way or another — this I want to tell you quite openly — an end must be made with the Jews.”

German servicemen who witnessed anti-Jewish atrocities in the Soviet Union after it had been invaded by Germany informed loves ones of what had transpired. As the reserve policeman Hermann Gieschen told his wife, “The Jews are being completely exterminated. Dear H, please don’t think about it, that’s how it has to be.”

The deportation of Jews from the Third Reich began in the autumn of 1941. In some cases, curses and chants from the local population were hurled at Jews as they were rounded up. The household goods of deported Jews were sold at public auctions. “From Swabian villages to … Hamburg, locals actively lobbied to take over their property,” Stargardt says, adding that in Hamburg alone the contents of 30,000 Jewish households were auctioned off between 1941 and 1945.

“Privileged” Jews were exempted from the first wave of deportations, as were Jews working in armament factories, Jews holding foreign passports, Jews who had Christian spouses and Jews who had compiled an outstanding service record during World War I.

Tellingly enough, the German media did not publish details of the deportations. Goebbels worked hard to suppress such news, knowing it might arouse antipathy among some Germans and be used in Allied propaganda campaigns against Germany.

By 1943, however, Germans were well aware that Jews were being murdered en masse and equated the pogroms with the Allied bombing of German cities, which claimed the lives of 420,000 civilians, Stargardt notes. August Topperwien, a captain in the armed forces and a teacher in civilian life, wrote in his diary of “dreadful events” that had unfolded in Lithuania. “We are not just destroying the Jews fighting against us, we literally want to exterminate this people as such!”

Goebbels, in the same year, delivered a major speech in Berlin’s Sportpalast in which he said, “The complete elimination of Jewry from Europe is not a moral question but one of the security of states.” By then, the gas chambers of Nazi extermination camp in Poland — Auschwitz-Birkenau, Sobibor and Treblinka — were operating around the clock, snuffing out the lives of thousands of Jewish men, women and children per day.

Post-war claims by Germans that they knew nothing about the Holocaust were simply lies. As he says, “Plenty of information circulated in wartime Germany about the genocide.”

Nazi Party membership rose from 850,000 in 1932 to 5.5 million on the eve of the war, driven by motives ranging from conformity and opportunism to conviction. But even among the highest echelons of German society, multitudes of Germans abhorred Hitler and sought the destruction of his regime. The most serious attempt to kill the supreme leader took place in the summer of 1944 when Colonel Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg, a member of the aristocracy, planted a bomb in Hitler’s field headquarters in East Prussia, lightly injuring him.

To Stargardt, the weakness of the assassination plot lay in its lack of high-level support in the army. With the exception of General Erwin Rommel, the head of the Africa Korps, and General Carl-Heinrich von Stulpnagel, the commander of German forces in France, the vast majority of plotters were officers of mid-rank.

The Nazi leadership emerged from it all with a more radical sense of purpose, determined to pull through the crisis and win the war. But as the Allies continued to inflict catastrophic battlefield defeats on Germany, there was a pressing need to lift morale. In 1944, Goebbels commissioned the largest and most lavish feature film ever to be made in the Third Reich. Turning on the 1807 siege of Kolberg and the German “war of liberation” of 1812-1813, Kolberg celebrated the spirit of resistance, but few Germans saw it.

During the final months of the war, Germany deployed a formidable force — one million soldiers, 1,500 tanks and armoured vehicles, 10,400 artillery pieces and 3,300 fighter planes — to fend off the Allied juggernaut, but to no avail. And attempts by Goebbels and SS chieftain Heinrich Himmler to forge a separate peace agreement with the Allies fizzled.

Nazi beliefs lingered on in Germany even after its unconditional surrender. A Catholic priest in Munster told investigators that the Allied bombing of Germany represented “the revenge of world Jewry.” And in Erlangen, the pastor Martin Niemoller was shouted down by students when he asked why clergymen in Germany had not condemned “the terrible suffering which we Germans had caused other peoples.”

American interviewers who fanned across the country taking the pulse of Germans found a curious detachment from reality. As Stargardt puts it, “Hardly anybody thought that the German people as a whole were responsible for the suffering of the Jews, although 64 percent agreed that the persecution of the Jews had been decisive in making Germany lose the war.”