I started reading The New York Times as a university student, which means that a lot of water has flowed under the bridge since I discovered it decades ago.

I enjoy reading the Times mainly because its coverage of international news and American domestic affairs is superior, a cut above the tepid and often superficial fare offered by most dailies in North America.

But as consistently good and reliable as its reporting and analyses tend to be, mistakes are made. Tight deadlines and personal preferences and biases inevitably lead to factual errors or misconceptions. And let’s face it, journalism at the end of the day is only the first draft of history, so perfection should not be expected.

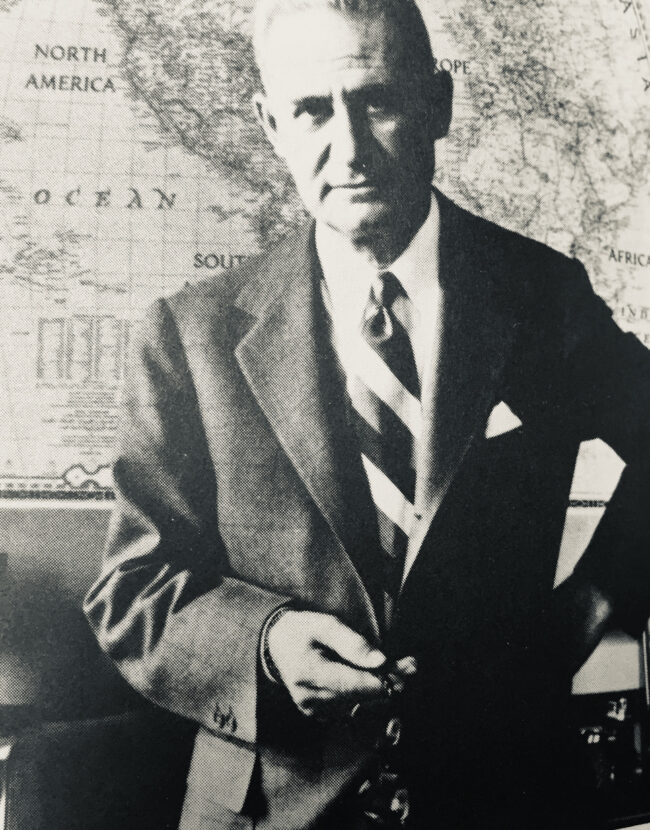

Ashley Rindsberg, a freelance journalist, essayist and novelist living in Israel, presents an unduly harsh appraisal of the Times, which has been known as the Gray Lady due to its reputation for bloodless objectivity.

The title of his new book aligns with his jaundiced opinion of its reporting record of major historical episodes over the past century. His argument is contained in The Gray Lady Winked: How The New York Times’s Misreporting, Distortions & Fabrications Radically Alter History.

In the preface, he suggests he has no preconceived agenda. It has “never been about opposing The New York Times, but about pursuing the same mission to which the paper is dedicated — unearthing the truth.”

Rindsberg, born in South Africa and raised in the United States, says that brand name publishers declined to publish his manuscript, while freelance editors and designers refused to work on it. They all feared retribution from the powerful and influential daily, whose slogan since 1897 has been “All the News That’s Fit to Print.”

No longer willing to keep it in his drawer, he decided to self-publish it under the imprint of Midnight Oil Publishers, his independent publishing company.

The Times, founded by newspaperman Henry Raymond, was bought by a German Jewish immigrant named Adolph Ochs in the late 19th century. Driven by the belief that the news should be delivered “impartially, without fear or favor,” he kept faith with that idealistic credo, Rindsberg writes.

“But his successors did not,” he adds, referring to Ochs’ son-in-law, Arthur Hays Sulzberger; the husband of his granddaughter, Orvil Dryfoos; his grandson, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger; his great-grandson, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr., and most recently, his great-great grandson, Arthur Gregg Sulzberger.

Rindsberg was impelled to write this book after stumbling across a footnote in William Shirer’s monumental memoir, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. “Shirer mentioned, almost casually, that on the eve of the outbreak of the Second World War, The New York Times reported that Poland had invaded Germany.”

Shocked by this glaring lie, Rindsberg delved into the Times’ digital archives. Sure enough, it had reported that Germany invaded Poland after Polish troops attacked a German radio station in the town of Gleiwitz. The attackers were, in fact, prisoners from a Nazi concentration camp who had been forced into this grotesque masquerade so as to provide Germany with pretext to march into Poland.

Otto Tolischus, the Times correspondent, fell for this ruse, presenting only the German propaganda point of view in his skewed story. He wrote, “Charging that Germany had been attacked, Chancellor Hitler … this morning issued a proclamation to the army declaring that from now on force will be met with force …”

As Rindsberg bitterly notes, Tolischus won the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for his dispatches from Berlin.

He goes on to say, “The story opened my eyes to a different understanding of The New York Times than the one I had held for years as a reader of the paper. Once my eyes were open, I could never close them again. I dug deeper and deeper, looking at some of the major historical events of modern history, including the Holocaust, the Vietnam war, the development and use of the first nuclear weapons, the second intifada, and more recently, the emergence of race … as a defining issue of our time.”

His research, he notes, turned up not “mere errors or inaccuracies but whole-cloth falsehoods,” leading him to the conclusion that the Times too often “gave in to the temptation to fit the facts to a preconceived pattern.”

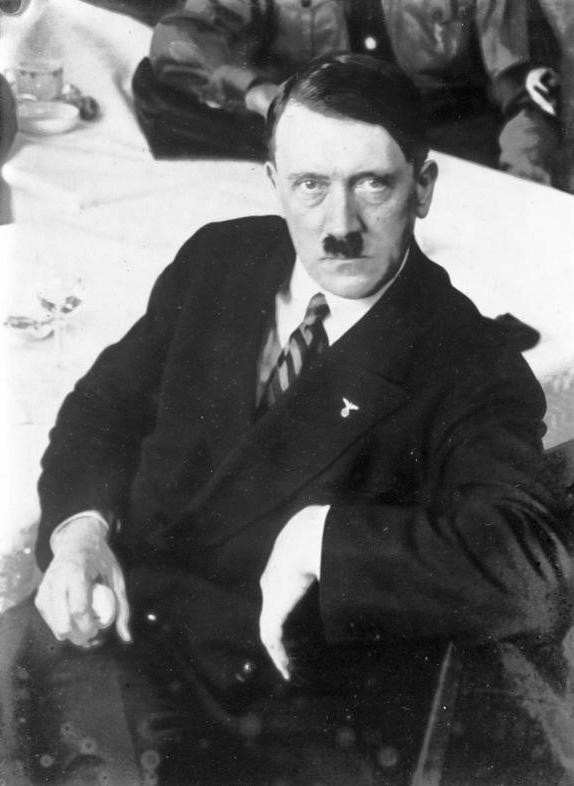

He starts his investigation in Germany, examining an article in the December 21, 1924 edition of the Times that made “the worst prediction” in the annals of modern journalism.

Reporting on Hitler’s release from jail following a failed Nazi coup d’état in Munich, the unidentified reporter wrote, “His behavior during imprisonment convinced the authorities that (he) was no longer to be feared. It is believed he will retire and return to private life and return to Austria, the country of his birth.”

Two years earlier, a Times reporter observed that Hitler was driven by “lofty, unselfish patriotism.”

Reporting on the summer Olympic Games in Berlin, another Times correspondent in Germany, Frederick Birchall, downplayed the persecution of Jews while praising the cleanliness of Berlin’s streets and the hospitality of its citizens. “The Times was struggling to ignore fifteen years of undisguised Nazi racism, jingoism, antisemitism, and predatory violence to maintain a delusion that maybe the Nazis were not so bad after all,” says Rindsberg.

In another piece, Birchall described Hitler as “one of the greatest, if not the greatest, political leaders in the world.”

It is tempting to excuse this lame coverage because the Times did not have the benefit of hindsight, he says. This explanation, however, does not hold up to scrutiny because some correspondents were not bamboozled by Nazi propaganda and reported the story very differently.

The Times’ bureau chief in Berlin, Guido Enderis, myopically claimed on the eve of the 1938 Munich conference that Germany was “desperate for peace and peace alone.”

In Rindsberg’s assessment, Enderis produced stories that were sympathetic, if not outright supportive, of the Nazi regime. Disgusted by Enderis’ “loud-mouthed defence of Nazism,” a Times reporter wrote a letter of complaint to the publisher, who stubbornly maintained the status quo.

After Hitler declared war on the United States, American reporters in Germany were detained, but Enderis was left alone due to his “friendliness to Germany,” as a German diplomat admitted.

Walter Duranty, the Times’ correspondent in the Soviet Union, won the 1932 Pulitzer Prize for his dispatches, which were marked by “scholarship, profundity, impartiality, sound judgment and exceptional clarity,” according to the judges.

Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin implicitly agreed with their appraisal. In 1934, he granted Duranty a rare interview. “You have a done a good job in your reporting, though you are not a Marxist,” he told Duranty.

Much to his discredit, Duranty denied that the Soviet government’s collectivization campaign in the Ukraine caused the catastrophic famine that led to mass starvation on an epic scale. “Duranty is still today widely associated with journalistic malfeasance on account of his attempt to cover up the Ukrainian famine,” says Rindsberg.

He adds, “Just as Enderis used Nazi news sources to report (or misreport) the onset of the Second World War, Duranty relied on extremely dubious, vague and unnamed sources … to report on one of the most consequential international stories of that decade.”

Years later, the Times considered the possibility of returning Duranty’s Pulitzer Prize, but then chose not to do so. Rindsberg provides an explanation: “The Ochs Sulzberger family … today is a mainstay of the left-leaning, educated and wealthy American intellectual elite that supported the Soviet ‘experiment’ and its utopian aims from the beginning.”

The Times’ handling of the Holocaust was generally disgraceful. “Of all (its) major failures, its coverage of the Holocaust is the most bitter and difficult to digest,” he says. “The owners of the … Times actually downplayed and, for all practical purposes, obscured the story of the Holocaust because they were Jewish.”

Fearing an upsurge of antisemitism, the highly assimilated Sulzberger family did not want the Times to be perceived as “Jewish” newspaper, and believed it would be playing into the hands of the Nazis if it identified Jews as a race, ethnicity or people.

In the course of 18,000 editions during the war, the Times printed Holocaust-related stories on the front page only six times, says Rindsberg.

One of its front page stories, concerning a New York City rally in 1942 condemning German atrocities, ran to 2,783 words, but did not make a single mention of the fact that Jews were being murdered.

Rindsberg is equally critical of the Times’ coverage of the U.S.’ wartime nuclear program. Its chief science writer, William L. Laurence, was fully aware that a nuclear device would cause radiation and kill and injure hundreds of people who had worked on it. Yet Laurence, a Pulitzer Prize recipient, “triumphed the beauty of the bomb” and “this terrifying new technology.”

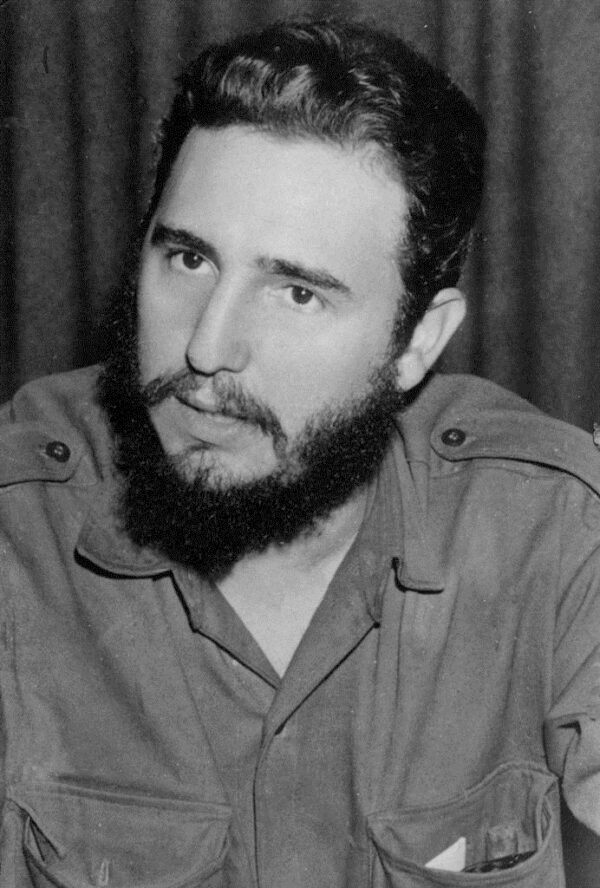

Rindsberg charges that Herbert Matthews, a Times reporter in Cuba, misrepresented Fidel Castro as a democratic reformer and claimed he was an anti-communist. Matthews replaced Ruby Hart Phillips because she was regarded as too sympathetic to the pro-American Batista regime. In choosing Mathews as her replacement, the Times ensured that its coverage of Cuba would be favorable to Castro, who would rule the island nation autocratically.

To Rindsberg, the Times “printed romantic stories of the rebels and their youthful vision of a liberated and democratic Cuba.” Matthews’ successor, Tad Szulc, followed his lead.

In one of his chapters, he lambastes David Halberstam, the “brash and brainy” Times reporter based in South Vietnam who, in the early 1960s, won the Pulitzer Prize. The dominant figure in a group of irreverent journalists who challenged the official U.S. version of the war, he predicted the fall of the authoritarian Diem government and went to great lengths to weaken it.

Rindsberg’s beef with Halberstam and journalists like him is that they relied on Communist propaganda fed to them by a North Vietnamese spy masquerading as a stringer in Saigon. His argument hangs by a thread and is less than convincing.

During the early days of the second Palestinian uprising in 2000, Mohammed a-Dura, an Arab boy in the Gaza Strip, was killed by gunfire. His final moments were captured on a brief video. Palestinian leaders blamed Israel in what Rindsberg calls “one of the greatest, most insidious and damaging propaganda blitzes in recent memory.”

Israel denied the accusation, and Rindsberg contends that a “blurry video does not prove Israeli responsibility.” Yet the incident, which was widely covered by the foreign press in Israel, had grave repercussions in the form of Palestinian suicide attacks against Israeli civilians and soldiers.

He implies that the incident was blown out of all proportion by these reporters. And furthermore, he criticizes Times correspondent Deborah Sontag for having contributed to the “fallacy” that the right-wing Israeli politician Ariel Sharon set off the intifada with a provocative visit to the Temple Mount in East Jerusalem.

Rindsberg, in another chapter, takes former Times reporter Judith Miller to task for having conveyed the false impression that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction prior to the second Gulf War in 2003.

He blasts the Times’ “1619” project, which was launched in 2019 to “reframe” American history. The series posited the theory that America was born in slavery rather than in liberty and equality. He denigrates it as a “subversion” of the truth that “distorted and warped” the real story.

In closing, Rindsberg acknowledges that, while the Times has been and still is a great newspaper, it is prone to “great failings.” His point is well taken, as a few of his more persuasive chapters on Germany, Russia and the Holocaust amply illustrate.

Yet Rindsberg’s sweeping indictment of the Times seems unfair and essentially wrong. The Times has hurtled off the rails on a few unfortunate occasions, as he shows, but it remains the gold standard in contemporary journalism.