The immortal words of Emma Lazarus’ poem, The New Colossus, are cast on a bronze plaque on the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor: “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

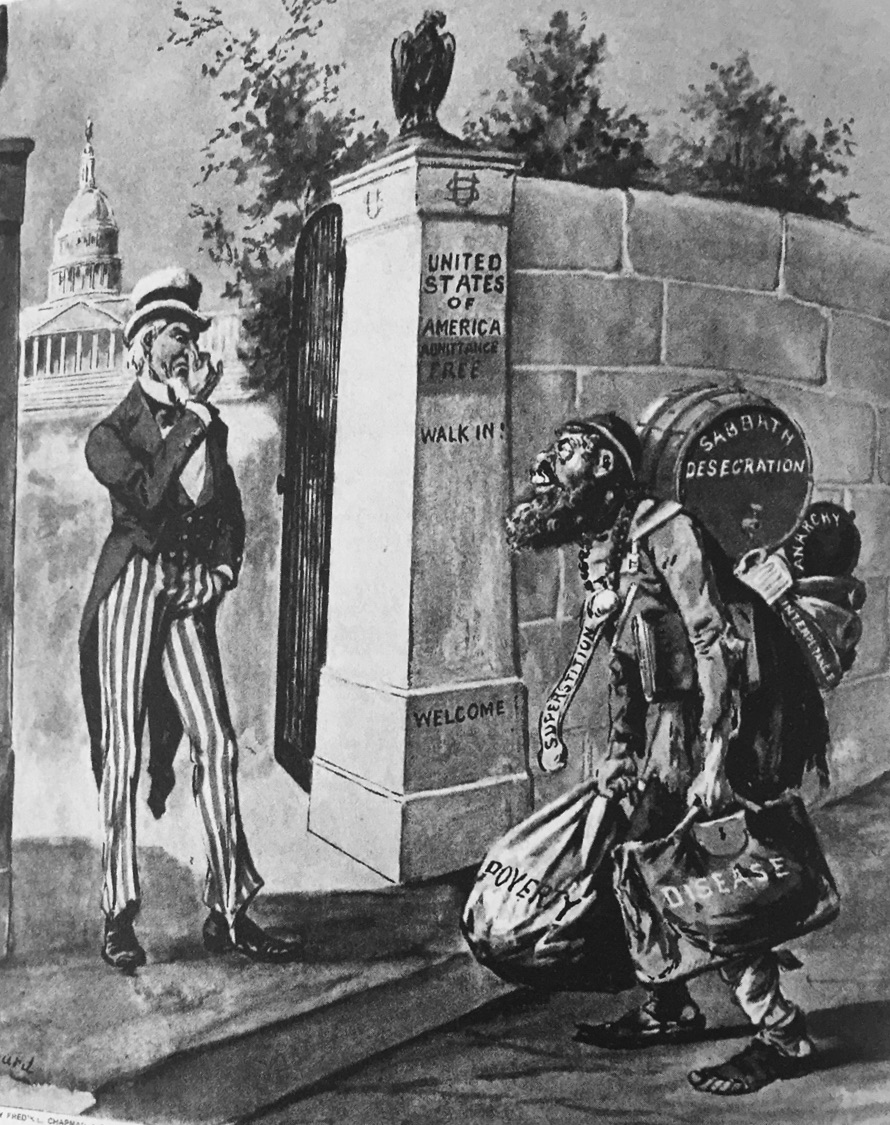

Some Americans cherished the philosophy underlying these sentiments, favoring a policy of mass immigration to the United States. Still others sought to keep newcomers, particularly Jews, southern and eastern Europeans, Africans and Orientals, far from its shores.

America’s anti-immigration movement, founded in the late 19th century by wealthy New Yorkers and Bostonians, was intent on maintaining the primacy of Anglo-Saxons and Nordics through very selective immigration. In support of their racist doctrine, they marshalled eugenicist arguments to underscore the “inferiority” of “lesser” races.

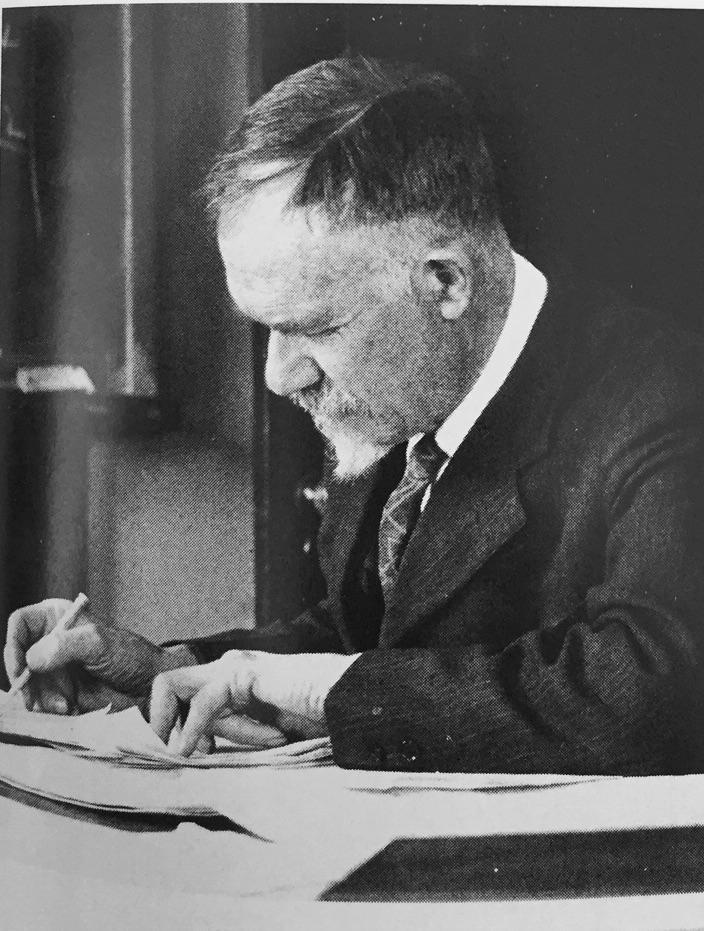

Daniel Okrent, an American Jewish journalist whose parents arrived in the United States from Poland and Romania in the first two decades of the 20th century, has written a rigorous account of this mean-spirited movement. The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics, and the Law that Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of America (Scribner) delves into it in vivid prose backed by thorough research.

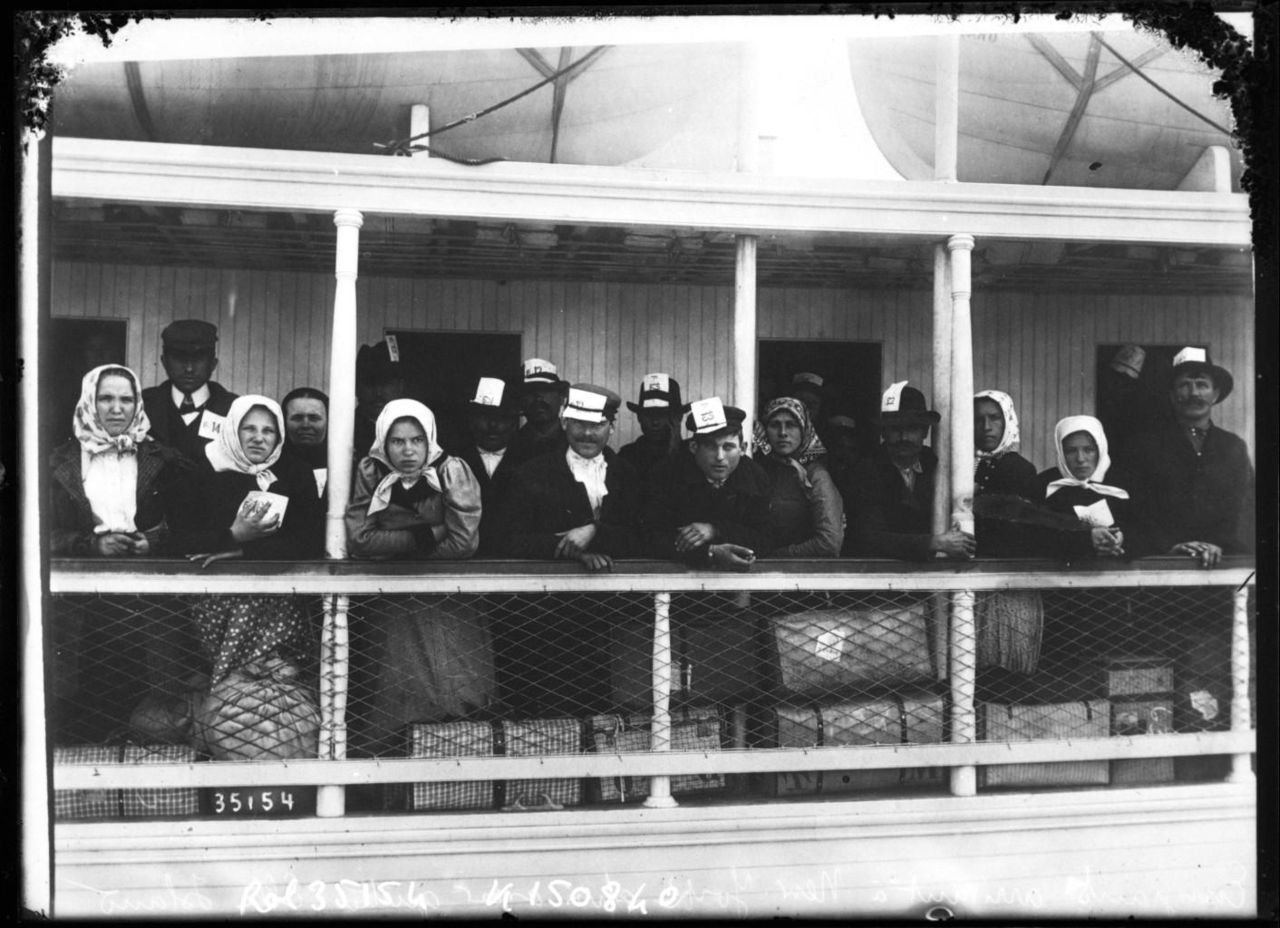

Barely one million immigrants streamed into the United States in the first 50 years of its existence as a nation. But between 1851 and 1860, 2.5 million immigrants poured in, the majority disembarking at Ellis Island in New York City. Their arrival sparked opposition from nativists, who earned the derisory sobriquet of Know Nothings.

Labor surpluses had a lot to do with their aversion to immigration. “But when the labor market was tight, principles were loosened,” he writes, citing President Abraham Lincoln’s plea to Congress in 1864 to encourage fresh immigration. In plain language, America had an expedient approach to immigration, always being ready to admit cheap labor when it suited its needs.

Orientals were the first to be rejected as immigrants, with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 halting the inflow of all “skilled and unskilled” Chinese laborers. In 1878, the U.S. Supreme Court had barred Chinese and other Asian immigrants from citizenship. These restrictions were endorsed by Samuel Gompers, the British-born Jewish president of the American Federation of Labor. As far as he was concerned, the Chinese “have no standard of morals.”

Anti-immigration sentiment surged as 11 million immigrants arrived in the United States between 1890 and 1910. With almost 80 percent of them hailing from southern and eastern Europe, warnings were sounded that America was destined to “join the lowly ranks of the mongrel races.” This idea had been gaining currency and was supported by leading scientific institutions and amplified by both reactionary and progressive activists.

Immigrants bound for the United States arrived by sea in a form of steerage travel perfected by Albert Ballin, a German Jew and the chief executive of the Hamburg-American Line, says Okrent. At one point, Ballin had a fleet of 175 ships at his command. To recruit passengers, he maintained a network of agents in the poorest parts of Europe.

Until 1882, fewer than 15 percent of all European immigrants entering the United States were from the southern and eastern regions of the continent. “Then everything changed,” says Okrent. Pogroms drove Jews out of the Russian empire, while grinding poverty and epidemics prompted Italians, Greeks, Poles, Serbs, Hungarians and Ukrainians to emigrate.

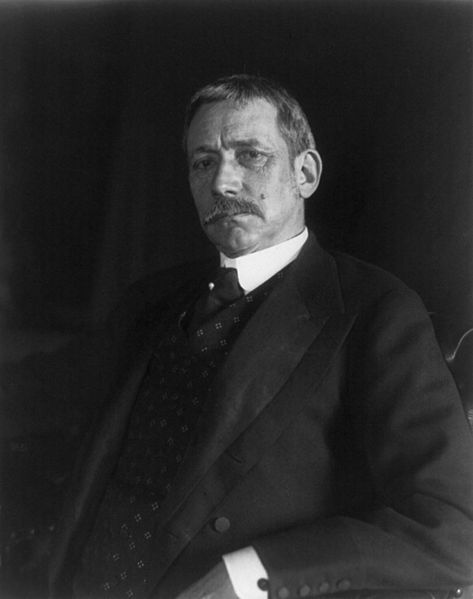

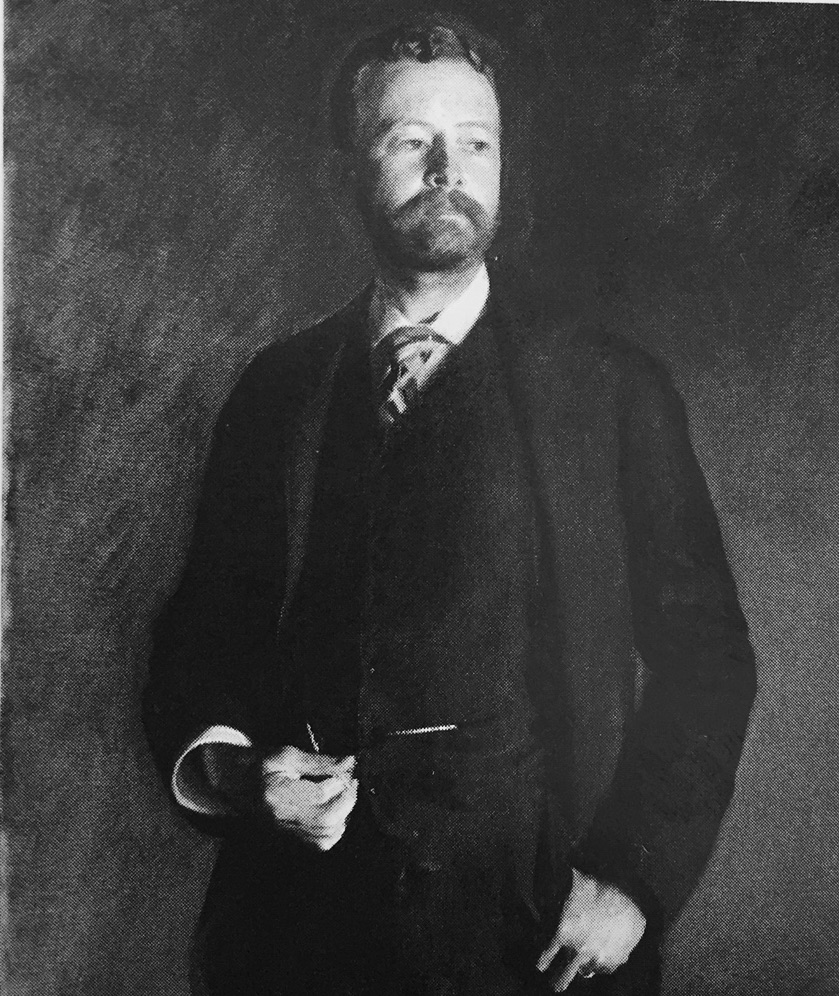

These immigrants struck some Americans, like the novelist Henry James, as aliens who would never fit into American society. U.S. Secretary of State Elihu Root, for example, compared immigration from southern Europe to “barbarian invasions.” Teddy Roosevelt, the president of the United States, shared his belief, claiming that the nation’s success, even its survival, depended on the preservation of the Anglo-Saxon elite.

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, whom U.S. Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes referred to as one of Boston’s “sifted few,” launched a campaign to restrict immigration by means of a literacy test. Lodge was honest enough to admit that while the test would mostly affect Italians, Russians, Hungarians and Asiatics, it would hardly touch English-speaking immigrants. He gained an ally in Francis Amasa Walker, the first president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who described the new immigrants as “vast masses of filth” from “every foul and stagnant pool … in Europe.”

Even open-minded progressives subscribed to such views. Walter Lippmann, the newspaper columnist, believed that immigration would have a “sinister effect on our national life.” Maxwell Perkins, who would edit the novels of Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, was of the same mind.

A handful of enlightened Boston Brahmins, such as Charles W. Eliot, the president of Harvard University, and Andrew Carnegie, the steel magnate, resisted this trend and endorsed a generous immigration policy.

While a few wealthy and assimilated Jews of German extraction, such as the banker Jacob Schiff, opposed Lodge’s literary test, most Jews of his class embraced it, fearing that their perceived position of acceptance, even privilege, would be imperilled by the arrival of an unwieldy number of Eastern European Jews.

Difficult as it may be to comprehend today, Jews from eastern Europe were dismissed as “uncouth Asiatics” by a leading German-language Jewish newspaper. Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the founder of the Hebrew Union College, the first Reform seminary in the United States, went as far as to say, “We are Americans and they are not.”

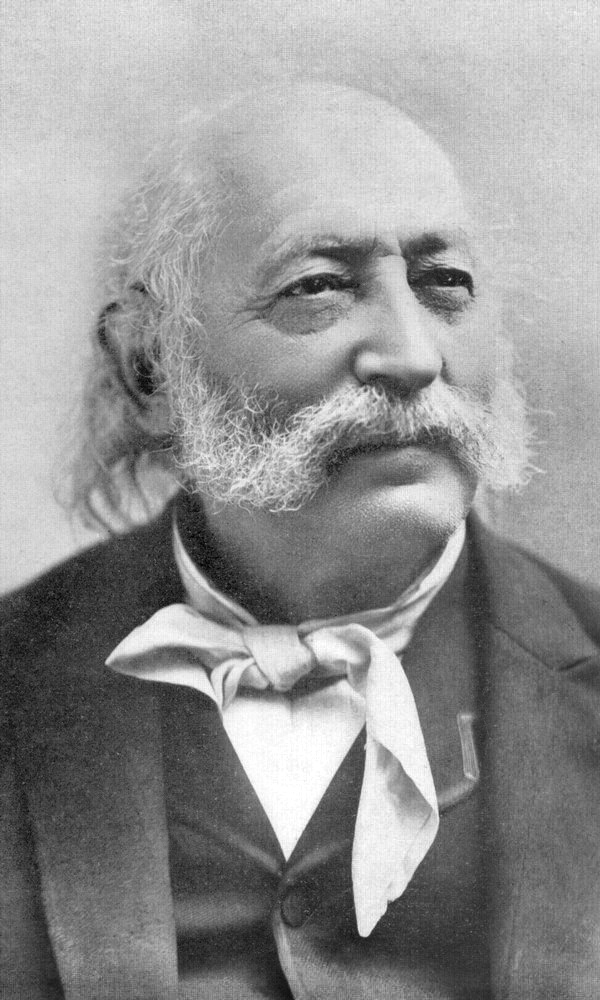

Charles Davenport, a Harvard faculty member, popularized the eugenicist argument, which gained tremendous traction after the first decade of the 20th century. He, in turn, was influenced by the British scientist Francis Galton.

Warning of the harmful effects of unrestricted immigration, Davenport wrote, “Unless conditions change, the population of the United States will, on the account of the great influx of blood from south-eastern Europe, rapidly become darker in pigmentation, smaller in stature, more mercurial (and) more given to crimes of larceny, kidnapping, assault, murder, rape and sex-immorality and less given to burglary, drunkenness and vagrancy than were the original English settlers.”

In accordance with this thinking, Davenport indulged in ethnic stereotyping, saving his most caustic barbs for Jews. “Though we love them, they nauseate us,” he said. As Okrent observes, Davenport certainly abetted the notions of scientific racism, but he was not as racist as some of his foul contemporaries. He expressed only “surprise” when his daughter married a Jew, and he denounced the antisemitism of Nazi Germany as “shocking violations of elementary human rights.”

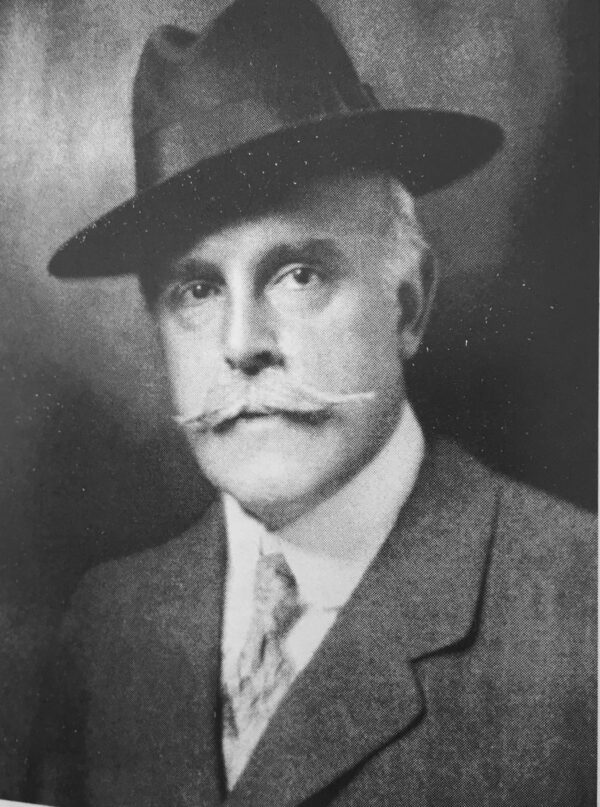

Certainly, Davenport was not as vicious as Madison Grant, an upper-class New Yorker and the author of The Passing of the Great Race, a work which glorified Anglo-Saxons and Nordics and defamed Jews. As Grant told one of his friends, the Jews of the Lower East Side were a “curse … draining off into this country (from) the great swamp” of Poland.

Only three months after the publication of Grant’s book in 1916, the literacy test was passed into law. It was followed by the 1917 Immigration Act, which, in essence, was a eugenic measure, as one of its advocates boasted.

During this period, Wilbur Carr, a career diplomat who headed the State Department’s Consular Service, produced a report describing Polish Jewish immigrants as “mentally and physically deficient, abnormally twisted and economically and socially undesirable.” His report was influential. Under the 1921 Emergency Immigration Act, immigration from Poland was cut by 70 percent.

U.S. President Calvin Coolidge extended these restrictions and capped immigration to 155,000 a year under the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, which drastically reduced the flow of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. “America must be kept American,” he declared. From 1925 until the beginning of World War II, an annual average of only 9,000 European Jews were permitted into the United States, compared to the previous figure of 50,000.

In his manifesto, Mein Kampf, first published in 1925, Adolf Hitler praised the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act. A decade later, an official Nazi handbook cited it as a model for Germany.

The United States’ wartime alliance with Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist camp led to the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Through the 1950s, President Dwight Eisenhower watered down the Johnson-Reed Act. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson officially replaced it with the Immigration and Nationality Act, thereby breaking with xenophobia and racism.

Okrent charts this important evolutionary process with skill and elan.