Fascist Italy under Benito Mussolini persecuted its Jewish citizens and played an integral role in deporting thousands of them to German extermination camps. Italy, nevertheless, has tried to distance itself from this shameful period, attempting to leave the misleading impression that Italians had only positive feelings for Jews and blaming Germany, its former ally, for these unparalleled crimes.

The false narrative that Italy has promoted was constructed, in part, by one of its leading historians, Renzo De Felice, who argued that Italians rejected antisemitism and that it was not embedded in their culture.

Italy’s post-war effort to whitewash its history and shed responsibility for its past does not withstand scrutiny, writes Simon Levis Sullam in his path-breaking revisionist work, The Italian Executioners: The Genocide of the Jews of Italy (Princeton University Press).

The facts are clear and unmistakable.

Italy, in 1938, passed draconian racial laws that immediately rendered Jews second-class citizens. Major Italian newspapers endorsed the legislation. Half of the Jews earmarked for death were seized by Italians rather than by Germans.

As the American historian David Kertzer notes in the foreword, Italy’s campaign of persecution against Jews was a crucial step toward the Holocaust. “Before people could entertain the idea of sending Jewish children and other defenceless Jews to their death, simply for being Jewish, they first had to rob them of their humanity, to cast them as dangerous enemies. This the Italians did with the imposition of the racial laws.”

The Italian Jewish community has been complicit in this coverup as well, says Sullam: “Italian Jewish institutions, seeking to acknowledge the help received by many Jews during the war, placed the greatest emphasis on Italian rescue efforts.”

Antisemitism emerged in the extremist fringes of the fascist movement from the mid-1930s onward, particularly in the pages of Roberto Farinacci’s newspaper Il Regime fascista. In the summer of 1938, Italian “racial scientists” released a manifesto proclaiming the superiority of the Italian race. A few months later, the Italian government enacted the first of its antisemitic edicts. As Sullam points out, fascist antisemitism drew on the age-old religious prejudices of the powerful Roman Catholic Church.

In his estimation, three prominent fascists set the tone of Italy’s anti-Jewish campaign — Giovanni Preziosi, a defrocked priest and journalist who administered the General Inspectorate of Race and produced the first Italian translation of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion; Giovanni Martelloni, the head of the Office of Jewish Affairs in Florence and a pseudo historian, and Giocondo Protti, a radiologist and lecturer who claimed that Jews were a “disease of humanity.”

Their malevolent theories were publicized by leading Italian dailies, notably Ill Gazzettino, which described Jews as “enemies” of the state; La Stampa, which accused them of being anti-Italian, and Corriere della Sera, which associated Judaism with various conspiracies.

Measures against Jews were stepped up following Italy’s entry into World War II on Germany’s side.

Starting in 1943, the Council of Ministers authorized the seizure and confiscation of Jewish property. In 1944, all Jewish communities were officially dissolved.

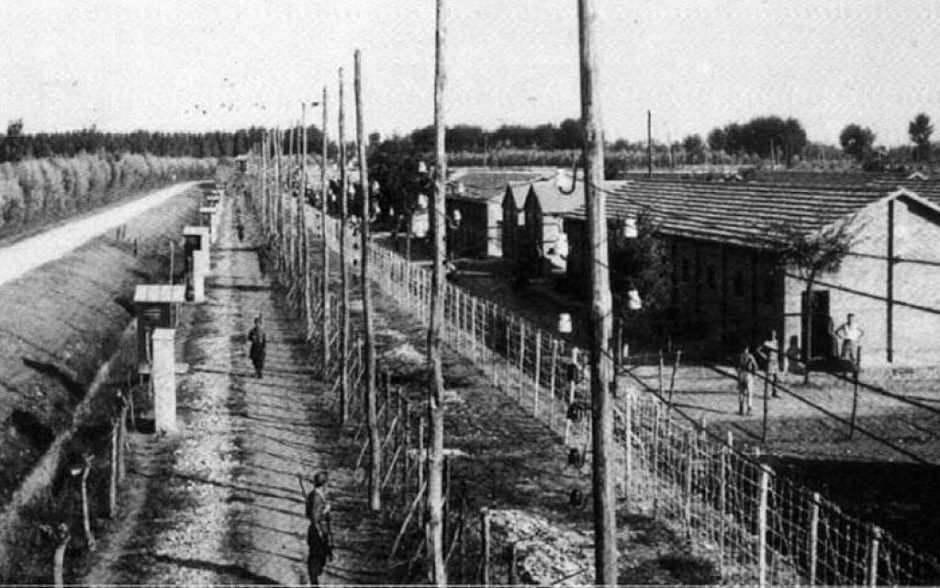

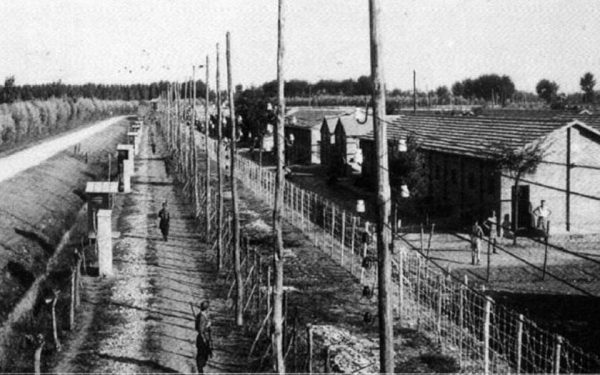

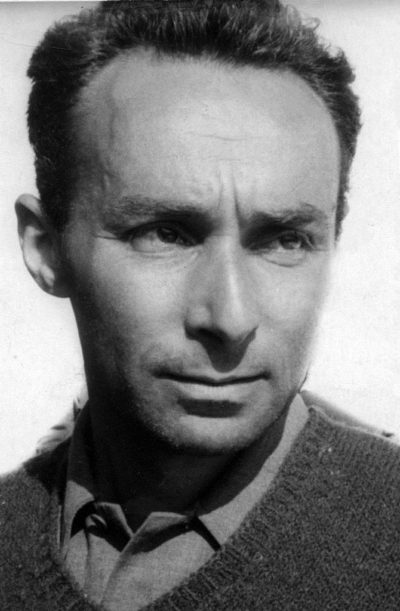

Italian Jews deemed “dangerous,” as well as foreign Jews, were interned in transit camps. One of these, Fossoli, near the city of Modena, was originally built as a prisoner-of-war facility. Among the prisoners held in Fossoli was Primo Levi, who would become an acclaimed novelist.

As Sullam says, the Ministry of Interior was “the most willing” of Italian collaborators to meet the demands of the Germans with regard to Jews. Police forces, too, were deeply implicated. The roundup of Jews, carried out by the Germans, received vital organizational support from the Italians, who supplied them with lists of Jews to be deported. Unlike in Vichy France, Italian fascists handed over Jews to the Germans without regard to their nationality.

German SS Captain Theodor Dannecker was initially in charge of the deportations, the first one of which left Milan for Auschwitz on December 6, 1943. His successor was Friedrich Bosshamer. Although the Germans made about 50 percent of the arrests, they always received organizational support from the Italians. In Florence, for example, German forces rounded up Jews with the assistance of a local Italian fascist gang, the Office of Jewish Affairs and the police.

Jewish deportees were placed on Italian trains that went as far as Italy’s border. Every convoy transported 500 to 600 Jews. From 1943 to 1945, 8,869 out of 47,000 Jews in Italy, or 19 percent of the total Jewish population, were deported. Most deportees were sent to Auschwitz, followed by Bergen-Belsen and Ravensbruck. In several instances, Jews were killed by Germans or Italians on Italian soil.

Of course, some Italian Christians helped Jews in their darkest hours.

But there was no shortage of Italians who informed on Jews. Among the informers were a handful of Jews, like Mauro Grini of Trieste and Celeste Di Porto of Rome. The fascists used their inside knowledge to ferret out Jews who had previously avoided arrest.

Six thousand Italian Jews found refuge in neutral Switzerland, but 8,700 were turned away. Guides who facilitated the entry of Jews into Switzerland could double their earnings by betraying their clients and pocketing a reward.

Shockingly enough, not a single fascist official involved in persecuting Italy’s Jewish citizens was put on trial after the war. “In general, the persecution of the Jews was not considered a crime,” says Sullam. And Italians who had applied racist legislation against Jews enjoyed distinguished postwar careers. He cites figures such as Carlo Alliney, who became attorney general in Palmero, and Gaetano Azzariti, who was chosen president of the Italian Constitutional Court.

Giovanni Preziosi, one of the most fanatical fascists, committed suicide in 1945. Giocondo Protti, the antisemitic propagandist, returned to his clinical practice. Giovanni Martelloni was acquitted of all charges due to an amnesty.

In short, Italy has failed to fully process the fascist era and has absolved itself of its crimes.

“The image of Italian benevolence and generosity — as opposed to that of the ‘wicked German’ — was at the heart of the judicial, diplomatic, political and historiographic interpretations of the behavior of the Italians that gradually become a deeply rooted stereotype,” says Sullam.

Kertzer is blunter in his appraisal: “Italy has yet to come to terms with its uncomfortable past. There has been no assumption of responsibility by the Italian state or its police force for the persecution of Italy’s Jews, or for their murder.”

Quite an indictment.