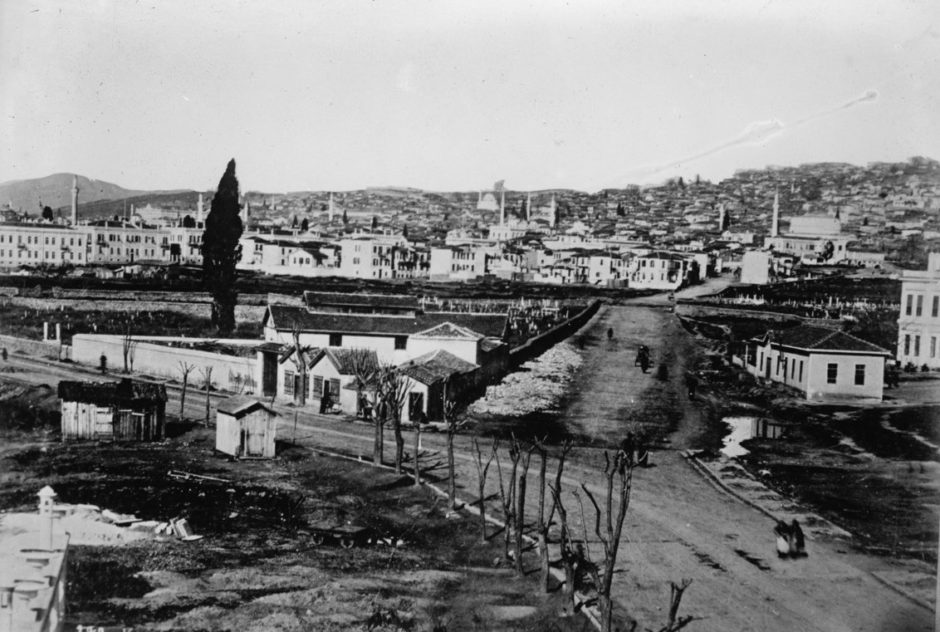

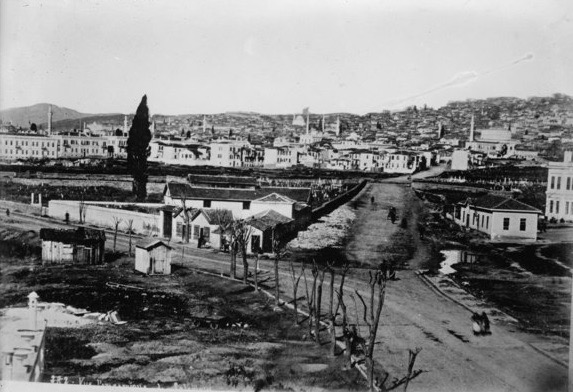

Known as the Jerusalem of the Balkans, Salonica — an Aegean port situated at the crossroads of Europe and the Middle East — was once home to the world’s largest Sephardic Jewish community. One of the jewels of the sprawling Ottoman Empire, the city was annexed by Greece in 1913 and renamed Thessaloniki, an upheaval that compelled its Jewish inhabitants to adjust to a new reality. Devin Naar’s Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece (Stanford University Press) is the first book to describe this tumultuous transition.

Naar, a professor of history and Jewish Studies at the University of Washington, has a personal interest in this topic. Salonica was where his paternal grandfather was born in 1917 and Salonica was where his grandfather’s two brothers and their families were rounded up by the Nazis in 1943 and consigned to their deaths in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Poland.

At the turn of the 20th century, the 500,000 Jews of the Ottoman Empire comprised 2.5 percent of its population of some 20 million. Around 15 percent of Ottoman Jews lived in Salonica, half of whose population was Jewish. The vast majority of Salonica’s Jews were Sephardim whose ancestors had been expelled from Spain in the 15th century, but several thousand were Ashkenazic Jews who had been driven out of the Russian Empire by pogroms in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Still others were Italian Jews from Livorno.

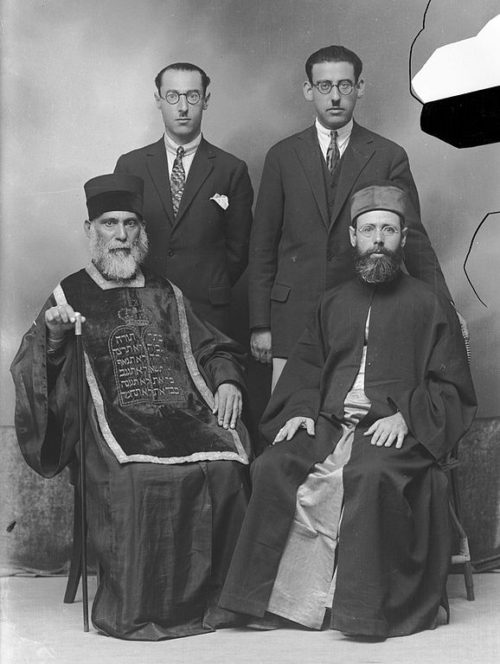

Like Christians, Jews were recognized as a distinct, largely self-governing community (millet) protected by imperial privileges. Jews, unlike Greek, Bulgarian and Armenian Christians, were intensely loyal to the empire in the sense that they did not seek political independence. “Fearing the fate of other non-Muslim populations, Jews emphasized their allegiance to the Ottoman state both out of sincerity and self-defence,” writes Naar.

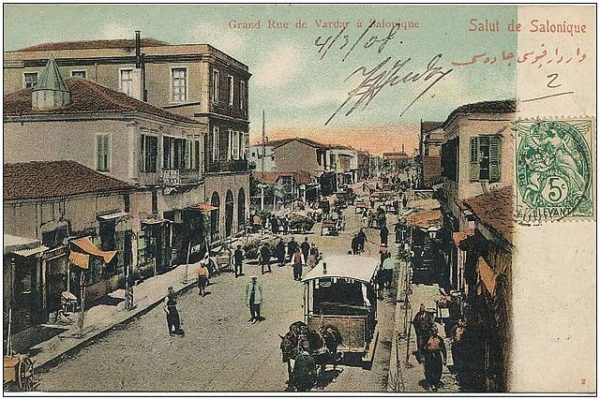

From a linguistic perspective, most Jews were not truly integrated into Ottoman society. Three quarters of Salonica’s Jewish residents in 1900 spoke only Judeo-Spanish, a variant of Latino, rather than Turkish. By that point, Jews were employed across the board as port workers, boatmen, retailers, merchants, civil servants and bankers. As Naar points out, impoverished Jewish families accounted for about half of the city’s Jewish population.

With the takeover of Salonica by Greece, a new order loomed, forcing Jews to develop “a repertoire of strategies to negotiate their position and reestablish their moorings in the changing political, cultural and economic landscape.” In practice, this meant that Jews had to make the wrenching transition from the multinational and multicultural Ottoman Empire to the homogeneous Greek nation-state.

Under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, half a million Muslims and Donme (Muslims of Jewish descent) were expelled from Greece and sent to Turkey, while one-and-a-half million Orthodox Christians were pushed out of Turkey and resettled in Greece. Jews were exempted from the population transfers, but the result was virtually the same. As Naar says, “Rather than transporting themselves to a different country, a different country had come to them.”

Greece, in the name of minority rights, recognized non-Christian citizens, like Jews, as distinct religious communities endowed with certain powers of self-government. But tensions between Jews and Orthodox Christians intensified “not only due to their different languages but also to enduring prejudices as reflected in continuing allegations that Jews killed Christ, periodic blood libel accusations, and economic competition.” Fanning the flames were slanderous allegations that Jews had murdered Greek rebels during the revolution of the 1820s. The popularity of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, translated into Greek in 1928, reinforced deep-seated antisemitic sentiments.

According to Naar, three events convulsed and weakened Salonica’s Jewish community.

The great fire of 1917 left 70,000 residents, including 50,000 Jews, homeless and destroyed 32 synagogues and Jewish schools, clubs and libraries. Victims were not allowed to rebuild their homes in what had been the heart of the Jewish neighborhood.

In 1924, the government introduced a Sunday closing law, overturning a custom that had permitted Jewish merchants to operate on that day.

Seven years later, spurred on by calumnies that Jews were disloyal to the state, a mob led by a right-wing organization, the National Union of Greece, burned down buildings in a predominately Jewish district.

“Although each of these events undermined the status of the city’s Jews and provoked waves of emigration, they did not result in the dissolution of Jewish life in Salonica,” says Naar. “Rather, each event compelled Salonica’s Jews to develop new forms of political and cultural engagement in order to retain a sense of Jewish collectivity, to solidify their connection to the city, and to foster a sense of belonging to the Greek polity.”

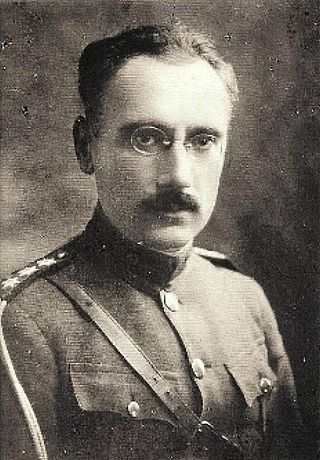

During this period of uncertainty, Prime Minister Eleftherius Venizelos urged Jews in Salonica to follow the example of their Romaniote coreligionists so as to secure a place for themselves in Greece. Residing in Greek lands since antiquity, especially in Ioannina, Romaniote Jews spoke Greek fluently, gave their children Greek names, and expressed their Judaism strictly through religion. “If Jews adjusted their cultural and political orientation, Venizelos suggested, they would become Hellenes and be accepted as such,” says Naar.

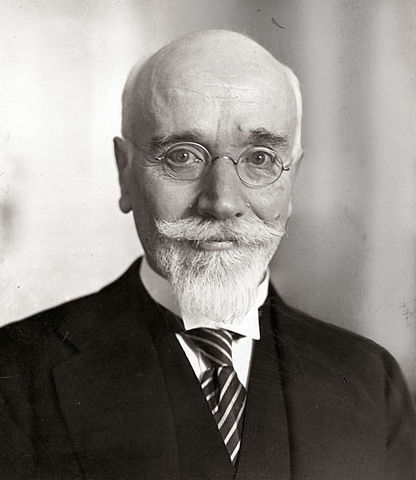

A handful of Jews took his advice to heart and joined the Greek armed forces, tripling the number of Jewish officers from two to six by 1938. Probably the most famous of the lot was Colonel Mordehai Frizis, who was killed in the line of duty fighting the Italian army in 1940 and 1941.

Just two years later, some 40,000 Jews in Salonica were rounded up by the German occupation forces and sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. “The almost total annihilation of Salonica’s Jews during the Holocaust was an unprecedented catastrophe, an irrevocable rupture in the centuries-long and demographically significant Jewish presence in the city,” says Naar. “Of the roughly 50,000 Jews in Salonica on the eve of World War II, almost all perished during the Holocaust, mostly in Auschwitz-Birkenau.”

Few Christians intervened to help Jews, given the huge social distance between Christians and Jews in Greece. “The most noteworthy exception to this dynamic tellingly arose not in Salonica but in Athens. In a letter of protest against the deportations of Salonica Jews, Archbishop Damaskinos implored (Greeks) to help their fellow persecuted citizens.”

The Nazi ethnic cleansing of Salonica unwittingly contributed to its Hellenization, says Naar. In the aftermath of this tragedy, the Jewish dimension of Salonica’s history was shunted aside. “The dynamic engagement of Salonica’s Jews in the politics, culture and economics of the city, in addition to their devastating destruction during the Holocaust, were for a long time expunged from the city’s history and public memory as part of a nationalizing process that sought to render Salonica exclusively and perpetually Greek.”

During this era, Salonica’s vast Jewish cemetery was levelled and on it arose the campus of Aristotle University of Salonica.

This indifference toward Jews on the part of Greece ended after the Cold War and Salonica’s designation as Cultural Capital of Europe in 1997. As a result, the fabled Jewish community of Salonica was finally given due recognition, says Naar in his insightful and cogent work.