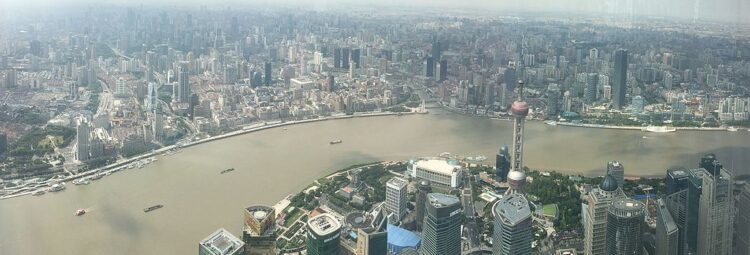

When I dropped into the cool and elegant marble lobby of the Peace Hotel, an exquisite Art Deco building overlooking the Huangpu River in central Shanghai, I was only vaguely aware of its storied history.

Although I did not know it was once called the Cathay Hotel, I knew it had been built by one of Shanghai’s wealthiest entrepreneurs, Victor Sassoon, the scion of an illustrious Sephardi family. Originally from Baghdad, the Sassoons were instrumental in shaping China from the first Opium War in 1842 until the Communist takeover in 1949.

Along with the Kadoories, another Jewish family from Iraq, the Sassoons were perhaps the first globalists. They established their business empire in Shanghai, the world’s fourth largest city by the 1930s. And as China’s westernized capital of commerce, finance, industry and culture, it had a skyline that rivalled Chicago’s and functioned as a foreign enclave outside the parameters of Chinese law.

In The Last Kings of Shanghai: The Rival Jewish Dynasties That Helped Create Modern China (Viking), Jonathan Kaufman, an American reporter who covered China for The Boston Globe and The Wall Street Journal, explains in vivid prose and in minuscule detail how they inspired and enabled a generation of Chinese businessmen to become successful capitalists.

Crediting the Sassoons and the Kadoories with creating a thriving entrepreneurial spirit the Communists wiped out but resurrected, Kaufman claims they “helped open the world to China, and opened China to the world.”

By his reckoning, the Sassoons played a key role in stabilizing China’s economy during the Depression and training the Chinese in global capitalism, thereby paving the way for China’s astonishing rise as a superpower.

The Kadoories, who decamped to the British colony of Hong Kong after the Communist revolution, ignited the manufacturing boom that would make China the hub of the international export market.

For decades after 1949, capitalists like them were denigrated as rapacious exploiters who lived in the lap of luxury as ordinary Chinese people struggled with poverty and squalor. And though the new regime tried to erase their legacy, it never really died.

Kaufman, in this fascinating volume, traces their ascent from the Middle East to the Far East.

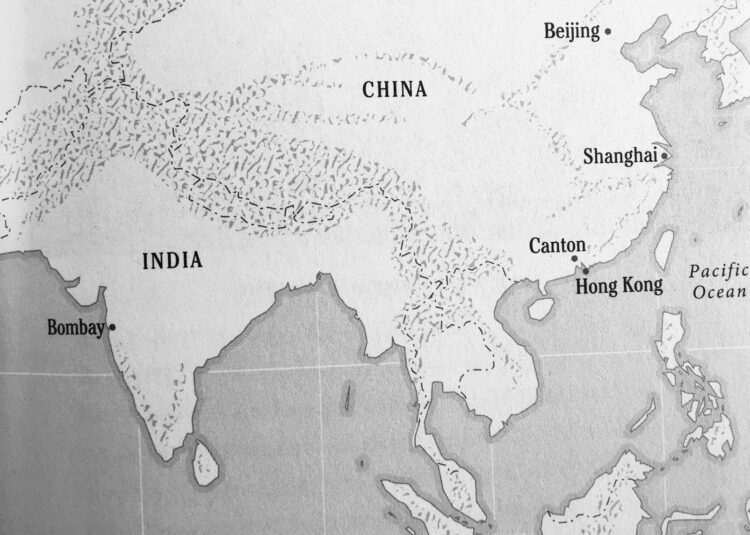

Known as the Rothschilds of Asia, the Sassoons were traders in gold, silk, spices and wool. Its patriarch, David, was a business prodigy and linguist who had been an advisor to Ottoman Turkish rulers in Baghdad before settling in Bombay in 1832. There, during a laissez-faire period in British India’s development, he built an empire administered by Iraqi Jews whose skills had been sharpened at his special schools.

Seven years after his arrival in India, Britain invaded China during the first Opium War. Under a 1842 treaty, China ceded the island of Hong Kong to Britain and opened five cities, including Shanghai, to Western trade. Supportive of Britain’s invasion, Sassoon entered the highly lucrative opium trade, which China deemed illegal.

Sassoon sent one of his sons, Elias, to China. He paused in Hong Kong before moving to Shanghai, where he sold opium, Indian spices and wool and bought silk, tea and animal hides. Several of Elias’ brothers were also dispatched to China, and like all the Sassoons, they never learned Chinese. Nonetheless, they amassed immense wealth.

The Sassoons fought vigorously against efforts to limit or ban opium, which yielded the family immense profits, but it was eventually banned, prompting them to invest in real estate and factories.

Elly, the patriarch of the Kadoories, learned the rudiments of the jute, coffee and textile trades from the Sassoons. Then he struck out on his own, forming an alliance with a Eurasian businessman in Hong Kong named Robert Hotung. They acquired interests in an electric company, hotels and a mechanized tram that ascended to the Peak, the highest mountain in Hong Kong.

Elly and his patrician British wife, Laura, established themselves in Shanghai, a frenetic mecca for foreign investors, in the early 1920s. They were lured by modern conveniences, low taxes and a business-friendly environment. By the end of the 19th century, more than half of China’s new factories were located in Shanghai, dubbed the Republic of Merchants.

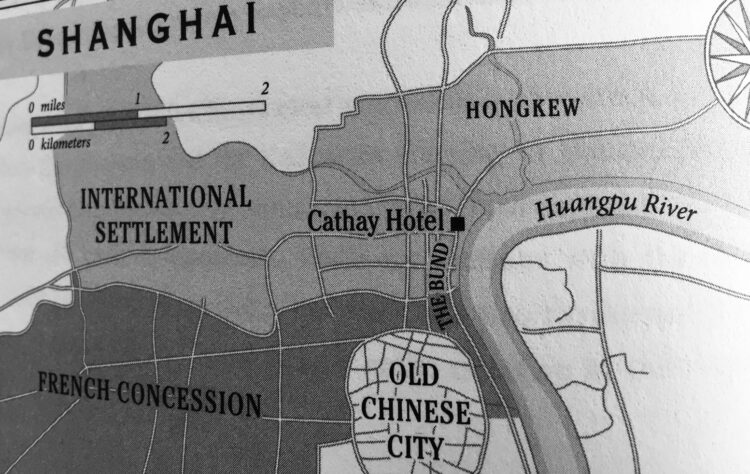

Forty thousand foreigners lived in Shanghai’s International Settlement, an extraterritorial area governed by Britain, during the 1920s. Three million Chinese were found in the rest of the city, the Paris of the Orient.

Elly and his two sons, Lawrence and Horace, who would inherit the company, thrived in Shanghai, but later moved much of their assets to Hong Kong, which turned out to be a wise and prescient decision.

Victor Sassoon, the grandson of David, was a playboy. During World War I, he was injured in an airplane accident that permanently crippled him, forcing him to hobble around in crutches. Born in London, he moved to Bombay to take charge of his family’s fortune. After a number of visits to Shanghai, he moved his holdings there.

At the intersection of Nanjing Road and the waterfront, he constructed his headquarters. And nearby, he built a luxury hotel that carried the name Marco Polo assigned to China — Cathay. “Victor gave Shanghai its glamor, its frisson and mystery,” says Kaufman.

Though a hedonist, he was an astute businessman, acquiring textile mills, shipyards, a brewery, a bus company and car dealerships, all worth the equivalent of $460 million in today’s currency. Politically, Sassoon aligned himself with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist faction, which would cede power to the Communists.

By the 1930s, Shanghai was an open city controlled by China, Japan, Britain and France. Since a visa was not required for residence, Shanghai morphed into a magnet for Jewish refugees fleeing Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia.

The Chinese consul in Vienna, Ho Feng-Shan, was sympathetic to their plight. In 1938, without the knowledge of his government, he issued more than 4,000 visas enabling them to leave their respective countries. Some of the visa holders used the visas to escape to destinations like the United States, Palestine and the Philippines, but about 18,000 reached Shanghai.

When Ho’s superior, the Chinese ambassador to Germany, learned what he was up to, he was recalled. But he remained loyal to the Nationalists and subsequently served as Taiwan’s ambassador to Egypt, Mexico, Bolivia and Colombia. Prior to his death in 1997, he never talked publicly about his activities, but his rescue effort was much appreciated and bolstered by Sassoon and the Kadoories.

In 1938, less than a year after Japan invaded and occupied Shanghai, a Japanese naval captain, Koreshige Inuzuka, was posted to Shanghai. Inuzuka, having been banefully influenced by the Russian antisemitic tract, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, believed that Jews were masterminding intrigues against Japan. Unlike genocidal antisemites who sought to murder Jews, he wanted to harness their wealth and power to finance Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, particularly in the puppet state of Manchuko in northeast China.

Since Sassoon was reputedly the richest person in Shanghai, he approached him, coming away with the misleading impression that he was pro-Japanese. Animated by this patently false notion, Inuzuka recommended that Jewish refugees in Shanghai should be treated fairly and not expelled.

When the refugees began arriving, Elly Kadoorie and other Jewish leaders assisted them, providing the newcomers with rooms and meals and helping them find jobs. Kadoorie’s son, Horace, offered vocational courses to young people and started the Kadoorie School, which had an entitlement of 700 students in 1940.

Sassoon established a rehabilitation fund to aid 700 families.

Many of the refugees were sent to Hongkew, a one-square mile derelict district afflicted by epidemics which had been levelled during fighting between the Japanese and Chinese armies.

During the summer of 1942, Inuzuka was transferred to Manila, while German SS colonel Josef Meisinger, the so-called Butcher oif Warsaw, arrived in Shanghai with a diabolical plan to exterminate the refugees there. Insisting on a compromise, Japan decided to build a ghetto, or “designated area,” in Hongkew.

By this point, Sassoon had fled Shanghai, bound for India, having been warned he would be arrested on charges of disseminating anti-Japanese propaganda.

The Kadoories fared even worse, having been placed under house arrest in an internment camp. It was where Elly died in 1944.

The United States liberated Shanghai in 1945 and turned it over to Chiang Kai-shek. Two years earlier, the Americans and the British had agreed to end Shanghai’s extraterritoriality, thereby dooming the International Settlement and the convention that foreigners were above Chinese law.

“The bubble the Kadoories and the Sassoons had lived in since the 1840s disappeared,” writes Kaufman. “For the first time in more than a hundred years, the Chinese controlled the entire city.”

Sassoon, having resolved to dump his Shanghai properties, sent his cousin to dispose of them. Some were sold at a fraction of their real worth, but Sassoon kept the down-at-the-heels Cathay Hotel, which employed 1,100 workers.

The Chinese Communist authorities seized the rest of Sassoon’s portfolio, including his famous hotel, which was worth about $500 million. Done with China, Sassoon settled in the Bahamas and built what Kaufman describes as “a scaled-down tropical version of his onetime Shanghai empire.” Over the years, the embittered Sassoon family petitioned the Chinese government for compensation, but were rebuffed.

The Kadoories, having resettled in Hong Kong and having remained committed to China, lost much less during China’s nationalization campaign. Lawrence Kadoorie, the family’s chief executive, watched the fall of Shanghai as China’s commercial capital from the safety of Hong Kong.

One of their prime properties, China Light and Power, endowed Hong Kong with a dazzlingly bright skyline and a neon-emblazoned ambience at night. Their Peninsula Hotel is still considered one of the finest hotels in Asia.

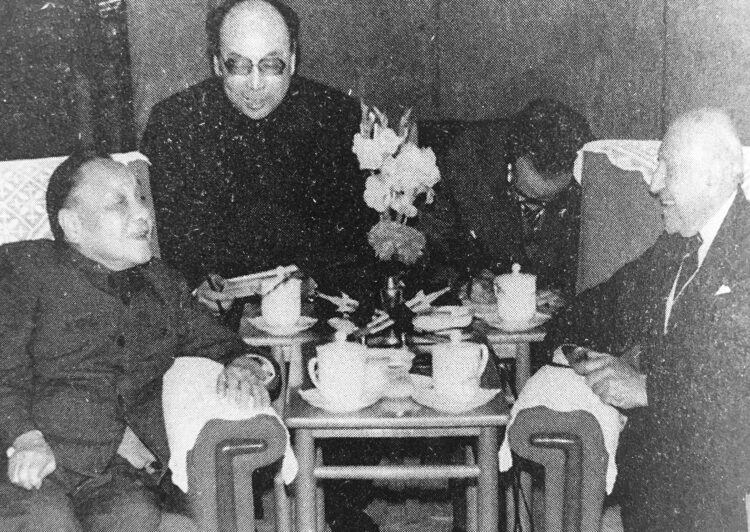

Today, the Kadoories, the first billionaires in Hong Kong, preside over an empire of real estate, electricity, factories and trading and finance companies. Their enduring influence is such that Lawrence was only the second foreign businessman to meet Deng Xiaoping, the modernizing ruler of China from 1978 to 1992.

Shunned by the Communist regime immediately after 1949, the Sassoons and the Kadoories are now “lionized and celebrated,” says Kaufman.

A portrait of Victor Sassoon and his American wife adorn a wall in the Peace Hotel, which was renovated in 2007. The Kadoories have opened a Peninsula Hotel in Shanghai, which again is a bustling metropolis. “Cosmopolitan, sophisticated Shanghai has returned,” he says.

Hongkew, once threatened with demolition has been transformed into what Kaufman derisively calls a “Jewish Disneyland.”

In closing, Kaufman acknowledges that the Sassoons and the Kadoories exploited Shanghai for their own mercantile ends, but also points out that they ignited an economic boom that has been greatly beneficial to China.