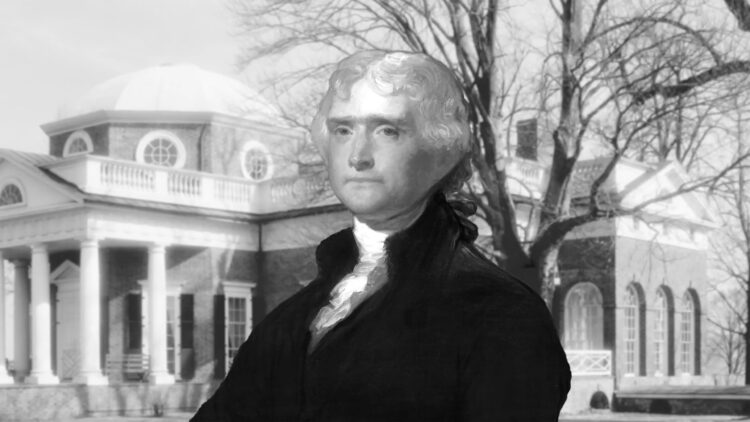

Monticello is one of the finest public buildings in America. Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States and the author of the Declaration Independence, lived there periodically until his death in 1826. When he died, he was deeply in debt, compelling his daughter, Martha, to sell the estate, which had fallen into disrepair.

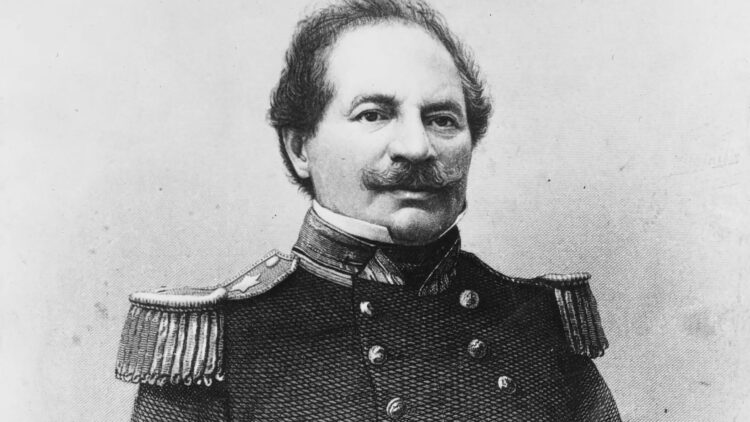

In 1834, Uriah Phillips Levy, a Jewish officer in the U.S. Navy, purchased Monticello, which lies in the wooded hills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge mountains. For the next 89 years, the Levys took care of it, saving it from mouldering away.

Their dedicated stewardship of Monticello, a UNESCO World Heritage site and a popular tourist attraction, forms the heart and soul of Steven Pressman’s first-class documentary, The Levys of Monticello, which will presented at this year’s Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs online and in-person from June 9-26. It offers commentary from an assortment of historians and Levy’s descendants and is educational rather than didactic.

Jefferson, whose presidency lasted from 1801 to 1809, spent three months of the year in Monticello, which was built by African slaves. Upon his retirement, he returned to the elegant residence, which was adorned with fine art and intricate scientific instruments he had collected over the decades.

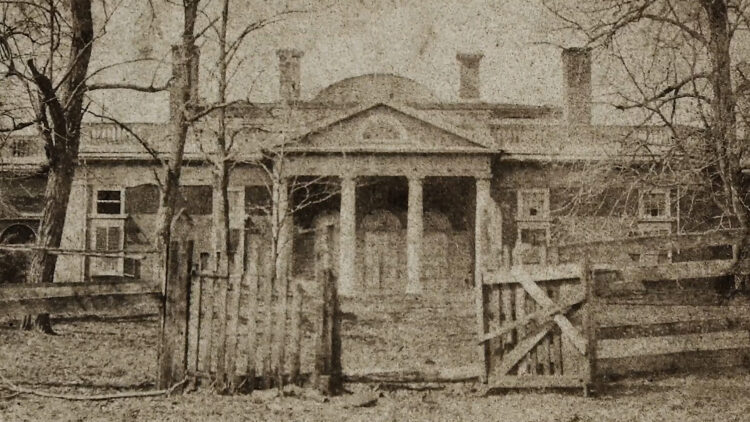

By the 1820s, Jefferson was in poor financial shape. As a result, he was unable to maintain Monticello. To pay off his debts, Jefferson’s daughter auctioned off his belongings and sold some of his slaves. In 1831, she sold the estate to James Turner Barclay for the grand sum of $7,000. Under his purview, Monticello continued to crumble.

Levy, born in Philadelphia in 1792, was the scion of a Sephardi family that immigrated to the United States in 1733. Although Levy never met Jefferson, he admired him and his concept of religious freedom.

From the moment he bought the property for $2,000, antisemitic snobs looked down their noses at Levy, a fifth-generation American whose ancestors were among the founders of Savannah, a city in the southern state of Georgia.

During this period, the United States was home to perhaps 2,000 Jews.

Levy was the butt of antisemitism during his 50-year service in the navy. Court-martialled six times and dismissed twice on what was widely regarded as trumped-up charges, he nonetheless rose to the rank of commodore, the first Jew to attain that status. He is probably best remembered today for having abolished flogging.

To the best of his ability, Levy carried out preventive maintenance of Monticello, though he never remodelled it. Levy’s mother, Rachel, died there in 1836 and was buried on the grounds.

Since Levy was a supporter of the union, Monticello was expropriated by the Confederacy following the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War in 1861. Levy’s brother, Jonas, supported the southern cause and flew the Confederate flag at Monticello.

Levy died in 1862, leaving Monticello to the U.S. government. However, the estate did not pass into its hands, and members of Levy’s extended family fought drawn-out legal battles for its possession. In the meantime, Monticello continued to decay.

Jefferson Monroe Levy — Levy’s nephew, a wealthy real estate speculator and a three-time congressman — purchased Monticello for $10,500 in 1879. Like Levy, Jefferson Monroe loved Monticello and furnished it with European artifacts, two statues of stylized lions and a portrait of his late uncle.

Maude Littleton, a wealthy and influential person, visited Monticello and left in a foul mood, convinced that a “rank outsider” and “alien” like Jefferson Monroe Levy should not be its owner or custodian. Her epithets, of course, were code words for unadulterated antisemitism, which flowered in the first half of the 20th century.

Littleton launched a national campaign to wrest control of Monticello from Levy, but she failed. Interestingly enough, Jefferson’s grandson sided with Levy during this dispute.

In 1923, Jefferson Monroe Levy reluctantly sold Monticello to the newly-created Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation for $500,000. He died in 1924 at the age of 77.

From that point onward, the Levy legacy was erased from Monticello, while Rachel Levy’s gravestone was neglected and allowed to deteriorate. But in the mid-1980s, at the direction of Daniel Jordan, the president of the foundation, the board belatedly recognized the Levy family’s contributions, refurbished Rachel Levy’s headstone, and installed a marker near it.

Pressman tells this story exceedingly well, giving the Levys the credit they so richly deserve.