It was a bolt out of the blue and it fizzled spectacularly.

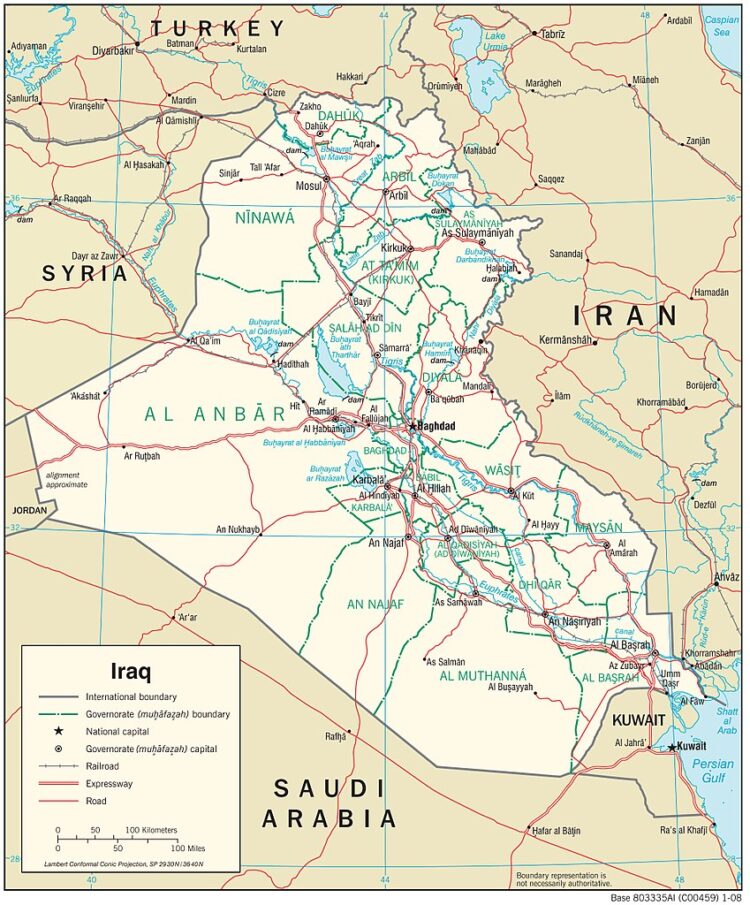

On September 24, 300 Sunni and Shi’a Muslim Iraqis attended an unprecedented conference in northern Iraq during which they called for peace and reconciliation with Israel, Iraq’s longtime enemy. It took place in Erbil, the capital of the semi-autonomous Kurdish region, which has unofficial ties with Israel.

In short order, the Iraqi government denounced it and issued arrest warrants against its key speakers, who received a torrent of death threats. Cowed and intimidated by the vociferous reaction, many of the participants recanted, claiming they had been duped into attending it.

In a telling juxtaposition, the meltdown occurred as Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid officially opened Israel’s embassy in Bahrain, a year after the two nations agreed to normalize relations, and the first commercial flight between Manama and Tel Aviv took off.

The normalization conference was organized by the Center for Peace Communications in Brooklyn. Founded as a non-profit organization in 2019 by Joseph Braude, an American Jewish author and broadcaster of Iraqi descent, its objectives are two-fold: to “resolve identity-based conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa” and to “roll back antisemitism and foster a culture of supportive relations with Israel.”

Its chairman, Dennis Ross, is a retired U.S. diplomat who played a leading role in trying to reconcile Israeli and Palestinian positions during the Oslo peace process from 1993 onward.

Braude, a Middle East specialist, expected a backlash, but went forward with the conference because a group of Iraqis requested his assistance.

The keynote speaker, Sheikh Wisam Al-Hardan, a tribal leader of the Sunni Awakening movement in Anbar province, focused on the emigration of more than 100,000 Jews from Iraq in the wake of the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948. The majority immigrated to Israel.

“The historical and cross-generational tyranny was manifest in the banishment and displacement, from which the Iraqi Jews suffered seven decades ago,” he said. “They lost the land which they built and inhabited as their homeland, in Mesopotamia, for 1,600 years. This history, which was unjust towards the Jews, severed one of Iraq’s arteries. We denounce this injustice in the strongest terms. At the same time, there was ethnic cleansing and genocidal massacres to which six million Jews in Europe fell victim. We see a glimmer of hope in the ability of some Iraqi Jews to rehabilitate their lives and to preserve their traditions through the generations. Most of them are still close to us, and we see them, as neighbors, in Israel.

“We publicly declare that we refuse to let Iraq fall victim to the mentality of warlords that destroyed Libya and Yemen, to the mentality of the tyrants of Syria, or to the scandals and tragedies of Lebanon, which was taken over by militias that spread corruption. On the other hand, we see promising signs of change in the region, especially with regard to the Abraham Accords.”

In a passage that doubtlessly riled many Iraqis, Hardan urged Iraq to join the Abraham Accords, whose signatories are the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco, and to establish full diplomatic relations with Israel.

Hardan’s speech, widely regarded in Iraq as a violation of a law that forbids contact with Israel and criminalizes the promotion of “Zionist principles,” set off a chorus of denunciations from the highest levels of government in Baghdad. Condemnations were issued by the president, a Kurd, and by the prime minister, a Shi’a Muslim.

Moqtada al-Sadr, a prominent cleric aligned with Iran, demanded the arrest of the participants. Chief among them were Sahar al-Ta’i, a Ministry of Culture official, and Mithal al-Alousi, a politician living in Germany who has long advocated Iraqi recognition of Israel.

Under intense pressure and threats, Hardan disavowed his comments as well as an op-ed piece under his name published by The Wall Street Journal. He claimed his intention had been to encourage a dialogue between Iraq and the Iraqi Jewish diaspora, not to foster Iraqi relations with Israel.

The entire incident underscored the deep-seated enmity that Iraq harbors for Israel, if not Jews.

Iraq’s venerable Jewish community, one of the largest in the Muslim world, was targeted by Iraqi nationalists in 1941, when mobs ransacked the Jewish quarter and killed scores of Jews in a pogrom known as the farhud.

With the birth of Israel, Jews came under immense suspicion and hostility, even though a considerable number were not Zionists and had no interest in making aliyah.

Iraq participated in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, and while several Arab countries signed armistice agreements with Israel after the fighting had ended, Iraq was the sole holdout.

Iraqi forces took part in the 1967 Six Day War. And in a tangible gesture of solidarity with Syria during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Iraq dispatched upwards of 30,000 troops and 250 tanks to the battlefield on the Golan Heights.

The Iraqi regime supported the Palestinian terrorist Abu Nidal, who ordered the 1982 assassination of Shlomo Argov, Israel’s ambassador to London. Argov survived, though he was badly injured. The shooting precipitated Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

During the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, Israel sold arms and munitions to Iran, whose Islamic regime called for Israel’s destruction.

In 1981, Israeli aircraft destroyed Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor.

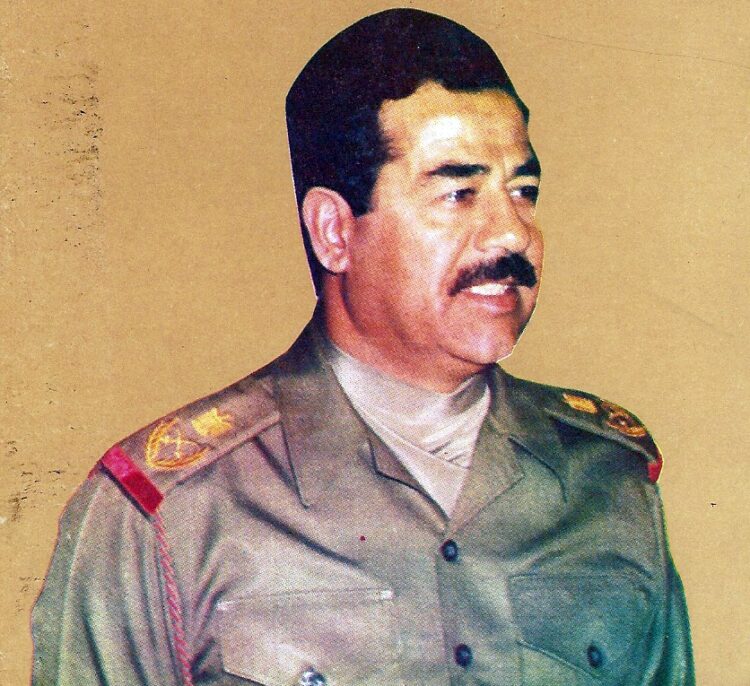

Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, a vocal advocate of the Palestinian cause, attempted to scuttle the international coalition ranged against him during the first Gulf War in 1991 by firing 39 Scud missiles at Israeli cities.

During the second Palestinian uprising, Saddam sent payments to the families of Palestinian terrorists who had been killed by Israel.

Given Iraq’s strong anti-Israel record, no one should have been surprised by its vehement response to the ineffectual normalization conference in Erbil. Although Saddam and his cronies were removed from the scene following the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Iraqi politicians, particularly those friendly to Iran, remain bitterly hostile to Israel. And public opinion tends to be pro-Palestinian and regards Israel as a pariah state.

If nothing else, the conference proved that some Iraqis are favorably disposed toward Israel. But they are definitely in a minority and are powerless to effect change in Iraq’s negative attitude to Israel.

Sad to say, Iraq is far from ready, politically or psychologically, to engage constructively with Israel.