The Middle East was on the abyss following two consequential events of immense magnitude — Israel’s incursion into Lebanon on September 30 and Iran’s ballistic missile attack on Israel less than a day later.

In what was described as a limited and targeted operation, Israel invaded Lebanon for the third time in 46 years, following Operation Litani in 1978 and the wars of 1982 and 2006.

It is unclear what the scale of its invasion will be and how long Israel intends to remain there. But it is entirely possible that Israel will expand its campaign in Lebanon and that it will be an open-ended one.

The battle has begun. The first Israeli soldier to fall in Lebanon, Eitan Oster, a 22-year-old officer, was killed yesterday.

The Israeli government decided that an invasion was necessary due to the failure of diplomatic efforts by the United States and France to achieve a ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah.

In a bid to stave off Israel’s military campaign, Lebanon’s caretaker prime minister, Najib Mikati, announced that the Lebanese government was belatedly prepared to fully implement a 2006 United Nations Security Council resolution that obliged Hezbollah to end its armed presence south of the Litani River, a distance of 30 kilometers from the Israeli border.

This was a meaningless gesture.

Makati had not even reached an agreement with Hezbollah on this pivotal issue, and his powerless predecessors, having been intimidated by Hezbollah, had done nothing about it. Nor was it clear how Makati proposed to implement Resolution 1701 without the use of force against Hezbollah, a state-within-a-state in Lebanon, which has been mired in an economic and political crisis since 2019.

Israeli commandos were operating in southern Lebanon prior to the invasion to prepare the ground for it. There were no direct clashes with Hezbollah fighters as these multiple raids unfolded. They focused on intelligence-gathering concerning Hezbollah positions close to the border and identifying Hezbollah tunnels and military infrastructure so that they could be attacked from the air or the ground. These sites were located in Lebanese villages and forested areas.

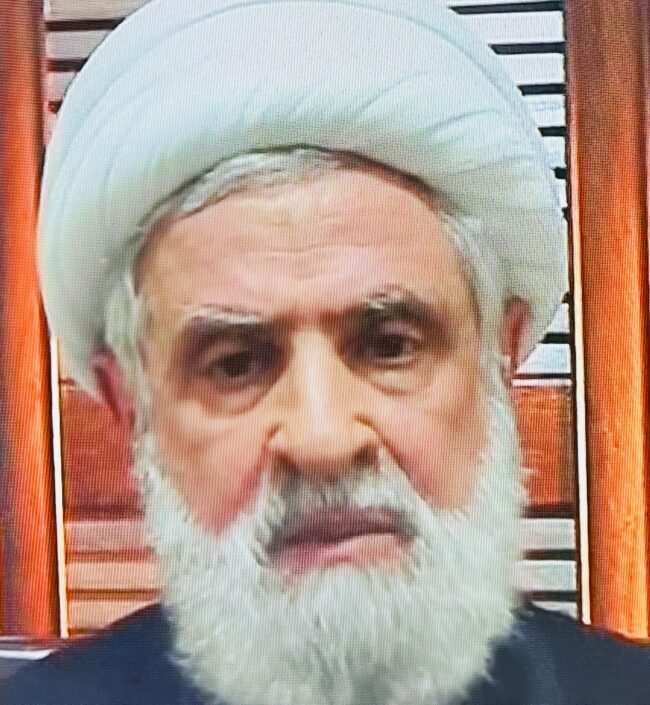

Hezbollah’s deputy leader, Naim Qassem, warned Israel three days ago that “the forces of the resistance are ready for a ground engagement” with Israel. This should not be construed as bluster. Hezbollah, having gained battlefield experience in Syria during its still ongoing civil war, has been preparing for this moment for years and will likely put up stiff resistance. In the meantime, Hezbollah is continuing to fire salvos of rockets at Israel.

The objectives of Israel’s current operation are two-fold: to destroy Hezbollah’s military infrastructure in the south and drive Hezbollah forces north of the Litani River in accordance with Resolution 1701 so that tens of thousands of displaced residents of the northern Galilee can safely return to their homes.

Israel resorted to this plan of action nearly a year after Hezbollah, in a tangible show of solidarity with Hamas, began firing what would be about 8,000 mortars, rockets, missiles and drones at Israeli communities in and around the Lebanese border. In the face of this unprovoked attack, Israel evacuated 60,000 people from the border area, fearing that Hezbollah would attempt to conquer it and murder and kidnap its inhabitants.

By Israel’s estimate, 2,400 Radwan Force operatives, plus 500 Islamic Jihad fighters, were primed to invade Israel shortly after Hamas killed roughly 1,200 people and kidnapped 251 Israelis and foreigners in southern Israel on October 7.

Less than day after Israeli forces entered southern Lebanon, Iran — Israel’s strongest enemy and the chief source of terrorism and instability in the Middle East — made good on its threat to exact vengeance on Israel for the assassinations of two of its key allies/proxies.

Ismail Haniyeh, a Hamas political leader, was killed in a bomb blast in Tehran on July 30, the day that Iran’s new president, Masoud Pezeshkian, was inaugurated. Hassan Nasrallah, the secretary-general of Hezbollah, was killed in Beirut on September 27 by an Israeli air strike.

In the past two weeks, Israel has managed to decapitate much of Hezbollah’s leadership and significantly deplete its arsenal of missiles and rockets. Yesterday, Israel killed Muhammad Ja’far Kasir, the commander of Hezbollah’s Unit 4400, which delivers weapons from Iran and its proxies to Lebanon, and Daw Alfakher Hinawi, the commander of the Imam Hossein Division, an Iranian militia which operates alongside Hezbollah.

These strikes represent a huge setback for Iran and its proxies in the Axis of Resistance, which is composed of Hezbollah, Hamas, the Houthis of Yemen, Iraqi militias and the Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad, and which was founded by the late Qassem Soleimani, who was assassinated by the U.S. in 2020.

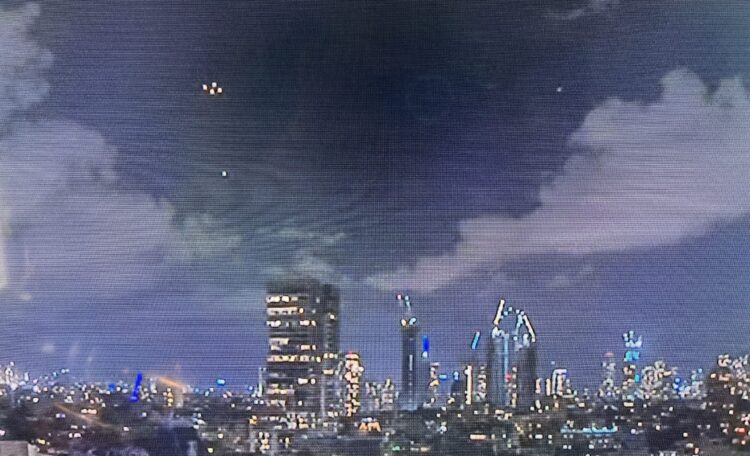

In the early evening hours of October 1, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps fired about 180 ballistic missiles at three air force bases — Tel Nof near Tel Aviv, Hatzerim close to Beersheba and Nevatim in the Negev Desert — and the headquarters of the Mossad, Israel’s external intelligence agency, in Herzlia.

The projectiles could be seen over Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem. Some crashed into residential areas, hitting an empty school in Gedera and a restaurant in Tel Aviv. Two Israelis in Tel Aviv were injured and a Palestinian in the West Bank was killed.

Most of the missiles were shot down by Israel, the United States and Jordan, though Iran claimed that 90 percent had struck their targets. U.S. President Joe Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, said that U.S. naval destroyers in the region had assisted Israel in downing the missiles, and that there had been “meticulous joint planning in anticipation of the attack.”

Biden called Iran’s attack “defeated and ineffective.”

The Iranian regime telegraphed its intention to retaliate, enabling the United States, Israel’s chief ally, to warn the Israeli government of the impending assault, Iran’s second direct air attack on Israel since the spring. On the eve of Iran’s bombardment, Netanyahu told Israelis that “days of great challenges” lay ahead.

Last April, following Israel’s bombing of the Iranian consulate in Damascus, Iran fired just over 300 missiles, rockets and drones at Israel. The attack was largely repelled by Israel, the United States, Britain and Jordan.

Hailing Iran’s missile attack as a “decisive response” to Israeli “aggression,” Pezeshkian, who had called for restraint, wrote on X, “In accordance with legitimate rights and with the aim of (establishing) peace and security in Iran and the region, a decisive response has been made to the Zionist regime’s aggression.”

In the aftermath of Iran’s onslaught, Netanyahu warned Tehran it had made a “big mistake” and vowed that “it will pay for it.” He added that “the regime in Iran does not understand our determination to defend ourselves and our determination to retaliate against our enemies.” Defence Minister Yoav Gallant wrote on X: “Iran has not learned a simple lesson — those who attack the State of Israel, pay a heavy price.”

Reports suggest that Israel may hit Iranian strategic infrastructure, such as oil or gas rigs, or even target its nuclear sites.

Israel’s military spokesman, Daniel Hagari, said that Israel would respond in a manner and time of its choosing.

Iran warned that Israel could expect a “crushing and ruinous blow” if it retaliates

The United States had already warned Iran of “severe consequences ” if it went ahead with an attack.

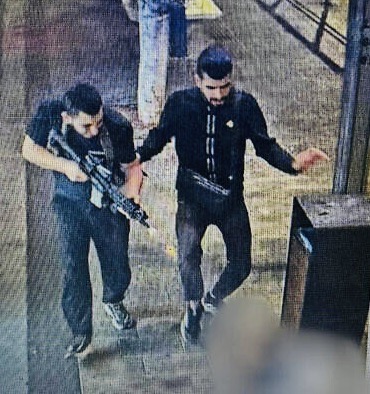

As these events played out, two Palestinian terrorists from the West Bank killed seven Israelis and wounded nine others in a shooting and stabbing attack in central Jaffa. It was one of the most serious terrorist incidents in recent years, underscoring the threat that Israel faces on a day-to-day basis.

Armed civilians shot and “neutralized” the terrorists, but the problem remains high on Israel’s agenda.