From 1947 until 1950, Canada admitted just over 98,000 European refugees, of whom 11,064, or 11 percent, were Holocaust survivors who had spent the previous postwar years in displaced persons camps in Germany.

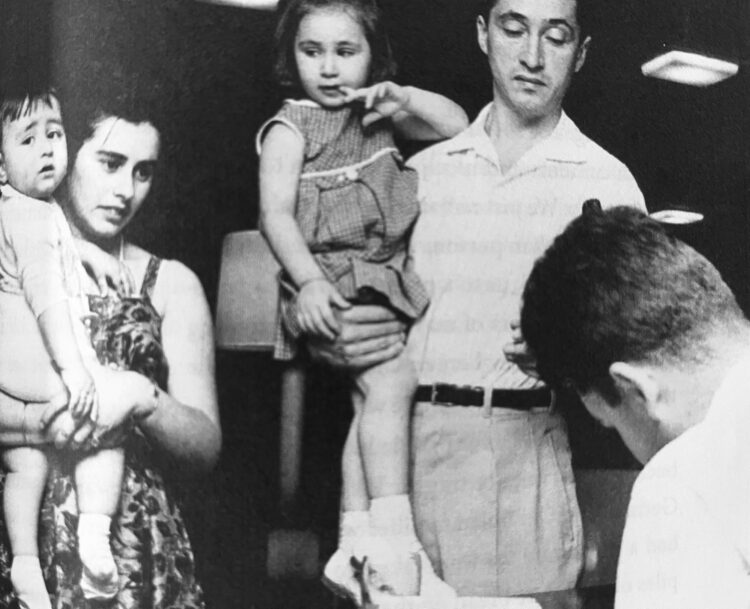

My late parents, David and Genia Kirshner, who barely survived the war in the Lodz ghetto, the last Nazi ghetto in occupied Poland to be liquidated by Germany, were among these new immigrants.

They were accompanied by yours truly, a toddler who was born in Bad Reichenhall, a spa in the Bavarian Alps, in the summer of 1946. Like the majority of the newcomers, we set down roots in Montreal, which was home to the largest Jewish community in Canada.

We left Germany from the port of Bremerhaven and arrived in Halifax in the winter of 1948. A train deposited us in Montreal, where I would be raised, in February of that year.

The Jewish refugees who came to Montreal during that period formed “a unique group of immigrants,” as Zelda Abramson and John Lynch write in The Montreal Shtetl: Making Home After The Holocaust, a comprehensive and readable account published by Between the Lines. “Canada did not have experience with immigrants who were victims of such atrocities, and their needs were different from those of immigrants of previous generations.”

“Their story is one of poverty, harsh living conditions, precarious work, and being stigmatized as newcomers,” they add.

Strangely enough, The Montreal Shtetl is the first ethnographic study of its kind. “This void in scholarship is curious, as 56 percent of Holocaust survivors resettled in Montreal, even though Ontario was the preferred place of settlement for other ethnic groups after World War II,” they note.

With their influx into Montreal, then Canada’s biggest city, the size of Montreal’s Jewish community swelled from 63,888 in 1941 and 80,788 in 1951 to 100,000 in 1958.

Their impact was considerable, according to Canadian Jewish scholar Ira Robinson, who argues that they “greatly contributed to the growth of the Jewish community demographically, economically and culturally.”

They reached Canada in three waves.

The first wave took place between 1947 and 1950, when many of the refugees were processed through labor programs organized by the Canadian Jewish Congress and the Canadian Overseas Garment Commission.

The second wave unfolded between 1951 and 1954 and included Jews from such countries as Israel, Sweden and France. They were sponsored by Canadian Jews and refugees from the first wave. Abramson and her family settled in Montreal by way of Israel during this wave. She left Montreal in 1971.

The third wave, from 1956 onward, was composed primarily of refugees from Hungary and Poland.

In their book, which is both academic and personal in tone, Abramson and Lynch focus on the first two waves.

Jewish DPs began arriving in Canada toward the end of 1947, entering a country that had been virtually closed to Jews for the previous 15 years. In 1931, the Canadian government passed an order-in-council favoring American and British citizens and farmers with sufficient means. All other classes of immigrants were prohibited.

The prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, hewed to a restrictive policy that discriminated against Jews. But due to labor shortages in Canada, he softened immigration regulations, and the first group of refugees permitted to enter Canada were 4,000 ethnic Poles.

C.D. Howe, the minister of reconstruction and supply, was an outspoken supporter of immigration, and he pressed King to let in DPs under a bulk labor scheme. The first such program, however, excluded Jews. But a small number of Jewish orphans and Jewish domestic servants were allowed into Canada under different immigration schemes.

In February 1947, the president of the Canadian Jewish Congress, Samuel Bronfman, and his right-hand assistant, Saul Hayes, met King and several of his cabinet ministers to request an addition to the bulk labor scheme.

With a shortage of skilled workers in Canada’s clothing manufacturing industry, which was mostly controlled by Jews, they called for a needle trade program to permit tailors, furriers and milliners to immigrate to Canada. The industry would underwrite the selection, transportation and settlement costs. They requested places for 1,000 workers and their families, and Canada agreed to their request.

The first batch of Jewish tailors reached Canada on December 5, 1947. By December 1948, 1,918 tailors had arrived in Canada, of whom 1,147 were Jewish. My father was among this group. By 1949, the tailors’ program had begun to wane, with only 432 tailors reaching Canada.

The Jewish refugees resettled themselves in a country suffused with antisemitism. As the journalist Pierre Berton commented, tourist resorts and golf clubs were off-bounds to Jews. Large corporations did not hire Jews. Jewish doctors could not get hospital affiliations. Universities rarely hired Jewish professors and enacted quotas for Jewish students.

By the late 1940s, these restrictions were falling and Canadian Jews believed they were on their way to assimilation and acceptance. But the arrival of the survivors induced in them a sense of insecurity and triggered lingering fears of a resurgence of open antisemitism. “Their disdain for the survivors was in fact a misplaced fearful reaction to their own potential marginality …” the authors write.

The Jewish refugees who settled in Montreal had no inkling of these fears as they moved into an overcrowded neighborhood known today at Mile End, where approximately 22,000 Jews lived. Mile End, or the St. Urbain Street ghetto, was bounded by St. Lawrence Boulevard and Hutchison Street and extended north from Pine Avenue to Van Horne Avenue.

The newcomers found accommodation in two and three-storey brick and stone cold water flats that were minimally heated by coal-fired stoves in kitchens. Due to the inadequate housing supply, renters were forced to pay extra in the guise of “key money.” Public baths were available to those who possessed minimal bathroom facilities.

“Here is where they began their life in Canada, found their first jobs, sent their children to their first Canadian school, and made use of the local social and cultural institutions,” the authors say.

The immigrants generally secured employment in the clothing factories along St. Lawrence Boulevard, which was often referred to as The Main. They obtained job through their own social networks or by knocking on factory doors. The jobs they found were often piecework, low-paying and seasonal. Usually, they toiled in sweatshops under difficult conditions.

Often referred to as “greeneh,” or untutored and unsophisticated newcomers, they compared themselves to “gheleh” (yellow ones), long-established Canadian Jews whom they likened to ripe bananas.

The greeneh, as one refugee told the authors, were “looked down upon to an extent” by Canadian-born Jews. As he says, “We had nothing to do with the Jewish Canadians. We felt welcomed by the Canadian Jewish Jewish Congress. Absolutely. They did everything in their power, I can only complement them totally. But beyond that, with the community, nobody really tried to make friends with us … We were the unknown quantity … They felt that anybody who survived had to be a manipulator or something.”

Another interviewee recalled, “We were not treated well by the Canadian Jews, especially youngsters … They thought we came from some primitive place … Very quickly we learned that we had to stay among the immigrants. We felt most comfortable among our own.”

Still another immigrant observed, “There was clearly a separation between the immigrant and Canadian Jews. The people who were born here … had one frame of reference. The immigrants who came off the boat understood the world differently … We had a story that no matter how sympathetic Canadians were, it was a hard story to appreciate from the outside … I also think there was a belief … that if you were a Holocaust survivor you were disturbed, damaged. This view lingered for decades … My parents did not integrate into Montreal Jewish life. They integrated into Montreal shtetl life, a world of friends and work.”

The authors, in compiling their research, interviewed 67 survivors and their children, nearly all of whom have interesting tales to tell.

Paul worked at the Castle des Mont, a hotel in Sainte-Agathe, a town in the Laurentian mountains north of Montreal. “We were hired as waiters, and we took the jobs away from the university students.”

Simka learned English from the poet Irving Layton. “The classes were terrific, although terrifying.”

Genia learned how to sew buttons on suit jackets before she met her husband, who was working in a sportswear factory earning next to nothing.

Renata rented a room from an elderly Jewish woman on Mount Royal Avenue who assumed she was ignorant of modern conveniences like toilets. “She didn’t understand that we came from a different background. We were urban and we were cultured.”

Olga, a hairdresser, and her husband, Max, a butcher, worked six days a week to accumulated enough money to buy their first home, a duplex.

Sonja’s father, a sheet metal worker, found a job as a roofer, while her mother landed a position as a sewing machine operator. “Our first year in Montreal was so, so difficult.”

Sidney, 17, worked as a sweeper and cutter in a dress factory. “I always had a job, and I think I was making something like $12 or $15 dollars a week. The jobs were not hard to come by. There was always somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody.”

The refugees struggled to adjust to Canada, but most of them were eventually successful. Within 20 years, the majority of their children had a post-secondary education, and many became professionals.

“Their story of integration and assimilation into Canada’s life had far-reaching effects,” write Abramson and Lynch. “The survivors’ settling in Montreal changed Montreal, and Montreal changed the survivors.”