One of Hollywood’s first anti-Nazi feature films, The Mortal Storm was released in June 1940, nine months after the outbreak of World War II. A black-and-white Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer production featuring an accomplished cast, it was directed by Frank Borzage and starred James Stewart as a German who opposes Adolf Hitler’s new Nazi regime.

Hollywood moguls, many of whom were Jewish, generally stayed clear of such politically-charged topics, being fearful of ruffling feathers in a country where their movies enjoyed popularity. This was especially the case in 1940, when the United States was a neutral power and still more than a year away from entering the war on the side of the Allies against Germany and Japan.

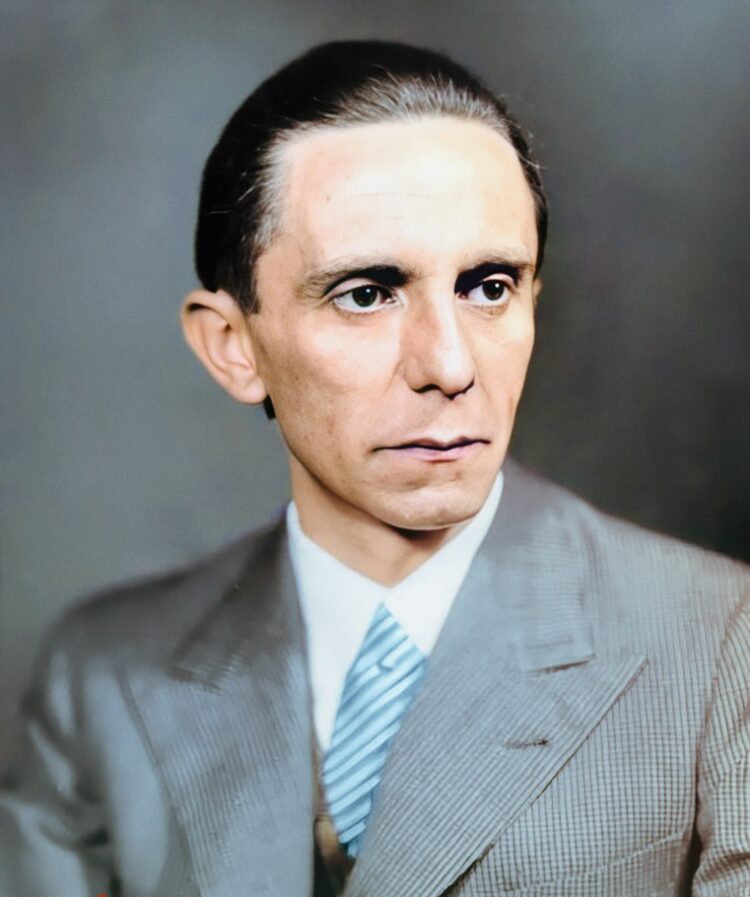

MGM, a Jewish-owned studio, went against the grain of this conventional wisdom, thereby offending Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, a vicious antisemite. Outraged by The Mortal Storm, he banned all MGM films in Germany.

Having watched it on the Turner Classic Movies channel, I understand why it upset Goebbels and his ilk. It pulls no punches in denouncing Hitler’s racist, totalitarian paradise.

It takes places in a small university town set in the majestic Bavarian Alps in the first month of 1933. Victor Roth (Frank Morgan), a professor of medicine, is celebrating his 60th birthday in the company of his loving wife, adult children and a few guests. He’s a happy man in his element.

At the university, his students greet him effusively and affectionately. One of them, Martin Breitner (James Stewart), shyly hands him a special gift. He accepts it gratefully.

Shortly afterward, medical student Fritz Marburg (Robert Young) announces his engagement to Roth’s daughter, Freya (Margaret Sullivan), whom Martin also loves. As they bask in this splendid moment, the family housekeeper rushes into the dining room to inform everyone that Hitler has been appointed Germany’s chancellor.

Fritz and Roth’s two stepsons are elated by the news, but Roth’s wife is deflated, wondering out loud what this means for “non-Aryans” like her beloved husband. His wife is a Christian, though her religion goes unmentioned. Roth is Jewish, but inexplicably, the film does not identify him as a German Jew.

Opposed to the new fascist order, Martin speculates it will bring nothing but persecution and war. One of Roth’s stepsons, an Aryan by Nazi definition, disagrees, saying that individuals must be sacrificed for the good of the state.

It is clear that Hitler’s accession to power has divided the Roth family.

Martin, reluctantly, joins Fritz and his friends at a crowded bar. Martin remains silent as they sing a song in praise of Hitler. In a heated conversation with Martin, Fritz argues that the adversaries of Nazism are enemies of the state. He then asks Martin when he intends to join the Nazi Party. That question is summarily settled after Martin, in disgust, watches Nazi thugs assault an opponent of the regime.

The film grows still darker when Fritz warns Freya that changes are coming that will affect her father adversely. “Because he’s a non-Aryan?” she asks archly.

Roth bumps into the new reality when he arrives on campus to deliver a lecture. His colleagues greet each other with a “Heil Hitler” salute, and a student, wearing Nazi regalia, provocatively asks Roth whether there is a difference between Aryan and non-Aryan blood. Displeased by his scientific reply, pro-Nazi students decide to boycott his classes.

In the following scenes, Nazi sympathizers burn “subversive” books in a roaring bonfire, while Freya reconsiders her engagement to Fritz after saying she can’t support a regime that will “persecute my people.” This is the closest Freya comes to acknowledging her half-Jewish ancestry.

As Germany is dragged deeper into the Nazi morass, Martin is assaulted by Nazis who happen to be his former friends. In succeeding scenes, Martin smuggles an anti-fascist into neighboring Austria and Roth is arrested. While in prison, Roth assures his wife that Germans will rediscover their “old virtues” again.

The Mortal Storm ends on a bitter-sweet note as Martin and Freya try to flee into Austria by foot and skis over rugged snow-clad mountains. They are pursued by armed Nazis.

The film, clocking in at one hour and forty minutes, makes its point expressively. MGM sounded the alarm about the Nazis a full year before they seriously launched their genocidal campaign against European Jews.