When World War I ended in 1918, a wave of antisemitic violence erupted in about 500 cities, towns and villages in territory contested by Ukrainians, Russians and Poles. During the course of this blood-soaked era, which coincided with the outbreak of a civil war in the newly-created Soviet Union, almost two-thirds of all Jewish homes and more than half of all Jewish businesses were looted or destroyed.

As these pogroms finally petered out in March 1921, well over 100,000 Jews had been killed and 600,000 Jewish refugees had been forced to leave their homes in what is now Ukraine.

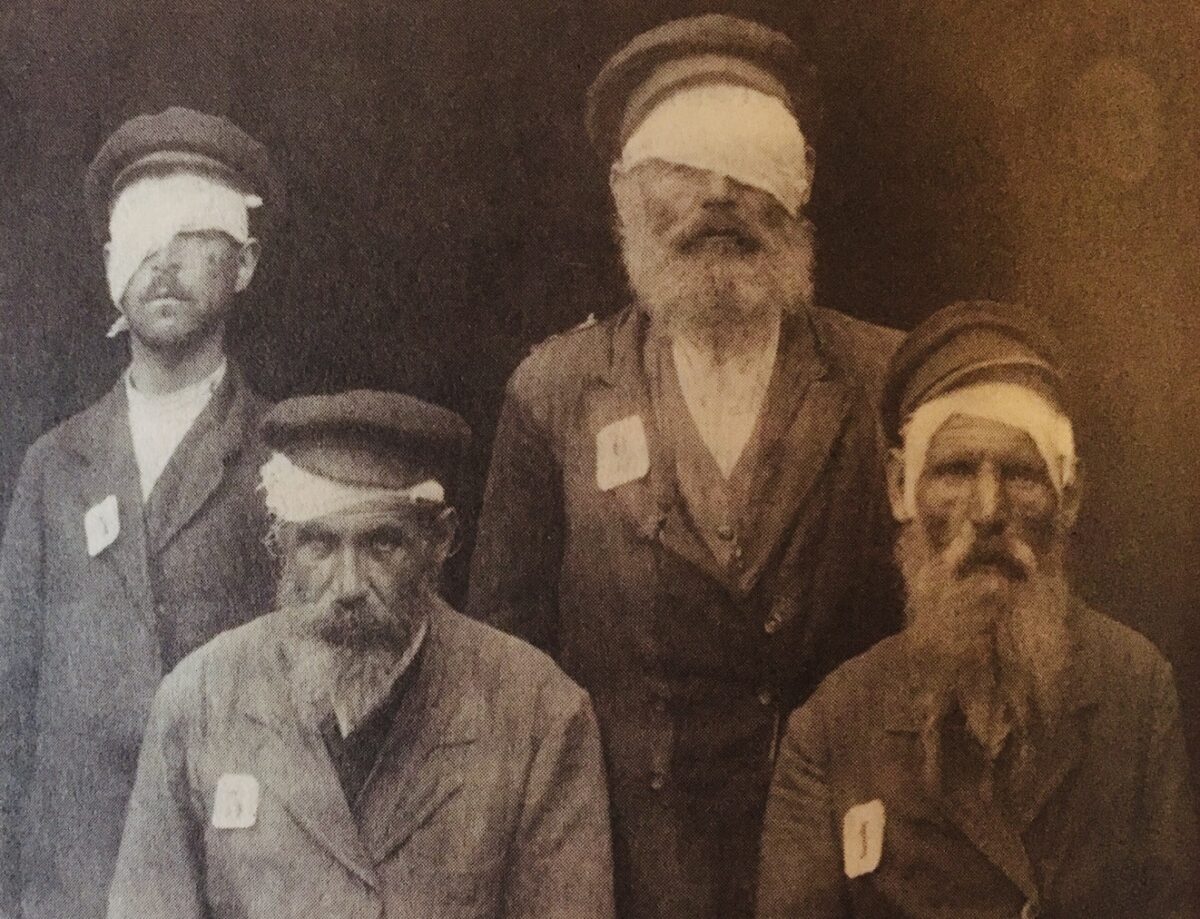

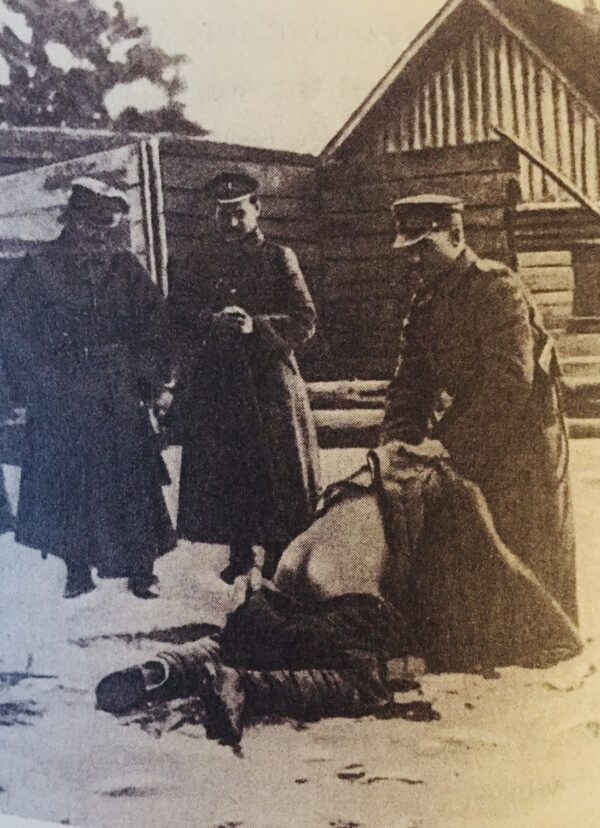

The perpetrators were Ukrainian peasants, Ukrainian armed bands and Russian and Polish soldiers. During their murderous rampages, the pogromists raped Jewish women and girls, humiliated and tortured Jewish men, pillaged Jewish properties, desecrated synagogues and ripped apart Torah scrolls.

Jeffrey Veidlinger, a professor of history and Judaic studies at the University of Michigan, has written a comprehensive and chilling account of this ugly epoch, a prelude to the Holocaust. He recreates it in his magisterial book, In The Midst Of Civilized Europe: The Pogroms Of 1918-1921 And The Onset Of The Holocaust, published by Metropolitan Books.

The pogroms occurred in what had been the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a multinational republic where Jews had generally flourished for hundreds of years. Encompassing the bulk of contemporary Ukraine, it was home to three million Jews, comprising about 12 percent of the majority population of Ukrainians, Russians and Poles.

As these lands fell under Russian rule, Russia enacted strict residency laws that restricted most Jews to an immense area known as the Pale of Settlement, located in the western provinces of the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Poland.

Jews there were an underclass, “differentiated from their neighbors by their religious practice, language, clothing, names, occupations, and by hundreds of discriminatory legal edicts imposed on them by a succession of tsars,” says Veidlinger.

In many of the small market towns, or shtetls, Jews made up one-third or more of the population, and their first language was Yiddish. They were mostly artisans, shopkeepers and petty merchants.

Jews coexisted with their Christian neighbors, yet led separate lives. They were dogged by antisemitic tropes and stereotypes disseminated by the church and by Ukrainian poets and writers such as Taras Shevchenko and Ivan Franko. Jewish estate managers and moneylenders, meanwhile, were accused of impoverishing the peasantry, while Jewish tavern keepers were blamed for peasant drunkenness. Jewish literature and folklore, produced by such writers as Sholem Aleichem, often denigrated Christian peasants as simpletons.

Antipathy toward Jews spilled over into pogroms, which unfolded from 1903 to 1906 in cities ranging from Zhytomyr to Odessa and in the blood libel trial of Mendel Beilis in 1913. And at the beginning of World War I, Russian troops murdered Jews in Brody, Lviv and Jaroslaw.

As Veidlinger points out, Jews were singled out for persecution by virtually everyone. “The Bolsheviks despised them as bourgeois nationalists. The bourgeois nationalists branded them as Bolsheviks. Ukrainians saw them as agents of Russia. Russia suspected them of being German sympathizers. Poles doubted their loyalty to the newly founded Polish Republic.”

In Ukraine, which would be absorbed into the Soviet Union in 1922, the Jewish role in the economy, combined with widespread rumors that Jews were stockpiling grain and speculating in currency, gave the spreading unrest antisemitic overtones.

The formation of the Ukrainian People’s Republic granted Jews, Russians and Poles a certain measure of autonomy. But it was soon at odds with the Kharkiv-based Ukrainian Soviet Republic.

A new round of violence against Jews broke out after the 1917 Bolshevik revolution and the emergence of the Soviet Union. Jews were targeted in pogroms by Ukrainian soldiers and Cossack horsemen, all of whom were convinced that Jews had supported the Bolsheviks.

Red Army soldiers participated in the violence as well, says Veidlinger. The problem posed by the Red Army attacking Jews prompted the Bolshevik leadership in the spring of 1918 to form a Commission for the Struggle Against Antisemitism and Pogroms, he says.

In that year, following the establishment of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic in Lviv, the Polish army attacked Jews in more than 100 localities throughout Galicia and in the Ukrainian city of Kyiv.

Ukrainian warlords, like Symon Petliura, committed anti-Jewish atrocities in towns such as Ovruch, Berdychiv, Zhytomyr and Proskuriv. However, in 1919, he issued a series of statements denouncing pogroms and blaming them on the Polish ruling classes, the Russian White armies opposed to the Soviet state, and the Bolsheviks.

Around this time, Bolshevik leaders again launched a campaign against antisemitism. Pravda, the leading Soviet newspaper, published a front-page article warning readers that anti-Jewish animus was synonymous with pro-tsarist sentiment. Pamphlets and brochures about the dangers of antisemitism were distributed to Red Army troops.

“The Bolsheviks had made a strategic decision to crack down on antisemitic violence and language, in part as a means of recruiting the Jewish population to their cause,” writes Veidlinger. The tactic worked. Jewish youths flocked to join the Red Army.

Yet many Jewish businessmen — property owners, shopkeepers and mill and factory operators — supported the Whites as defenders of private property and classical liberal values, he notes.

The pogroms had a profound impact on Jews, alienating them from the Ukrainian cause and driving them into the arms of the Soviet Union. “The association between Jews and Bolsheviks became a self-fulfilling prophecy,” he says.

In addition, the pogroms uprooted Jews. By 1926, when the first Soviet census was conducted, 42 percent of the 1.5 million Jews counted in Ukraine were no longer living where they had been born.

Six hundred thousand Ukrainian Jews fled abroad, joining White soldiers, the Russian aristocracy and bourgeoise and tsarist officials in exile. They migrated to Poland, Germany, Austria, Romania, France, Canada, the United States, Argentina, Palestine and even Turkey.

Twenty thousand refugees settled in the seedy Scheunenviertel district of Berlin. “Eastern European Jewish refugees were portrayed as rowdy and raucous and generally uncivilized, as having poor hygiene and being carriers of disease,” writes Veidlinger. The most serious accusation against the newcomers was that they bore responsibility for the crimes of the Bolsheviks, and that they were importing communism into the heart of Europe.

Petliura moved to Paris, where he founded a Ukrainian newspaper. In the spring of 1926, a young Ukrainian Jew named Sholem Schwarzbard assassinated him, reigniting interest in the pogroms. Many Ukrainians assumed that Schwarzbard was a Soviet agent. Most Jews regarded his assassination as justifiable.

A jury acquitted Schwarzbard of all charges, but his trial exacerbated Ukrainian-Jewish tensions. As Veidlinger puts it, “Petliura had become a hero to all Ukrainians and an archetypal villain to Jews — a precursor to Hitler.”

Petliura’s murder provided the Soviet government with an opportunity to denigrate the very idea of Ukrainian independence, to advance its own narrative of the pogroms as a relic of an imperial epoch, and to whitewash its own complicity in the violence. Pravda, in its coverage of Schwarzbard’s trial, depicted Petliura as a “murderer” and “pogrom monger.”

In response to the pogroms, growing numbers of Jews joined Soviet security agencies like the Cheka and its successor organizations. By 1939, the majority of Jewish officials had been purged from them.

As Veidlinger observes, the Soviet Union in its early years portrayed antisemitism as a counter-revolutionary weapon of reactionary elites. At the same time, the Bolsheviks tried to curry favor with Jews through Yiddish-language schools, theatres, film and literature. During 1920s and 1930s, Kyiv became a major center of Jewish life in the Soviet Union.

In accordance with its 1939 non-aggression pact with Germany, the Soviet Union occupied eastern Poland following the German invasion. Fearful of the Nazi regime, Jews welcomed the Soviets. Yet the Soviet occupation was not necessarily beneficial to Jews. As Veidlinger says, “Jewish artisans and shopkeepers lost their stores, businesses and workshops. Zionist activists and rabbis were arrested. Hebrew was repressed.” Yet the Soviet authorities removed all the restrictions Poland had placed on Jews, thereby arousing the resentment of Poles and Ukrainians.

Pro-German Ukrainian nationalists, notably Stepan Bandera, accused Jews of being “the most faithful (supporters) of the Bolshevik regime and the vanguard of Muscovite imperialism in the Ukraine.”

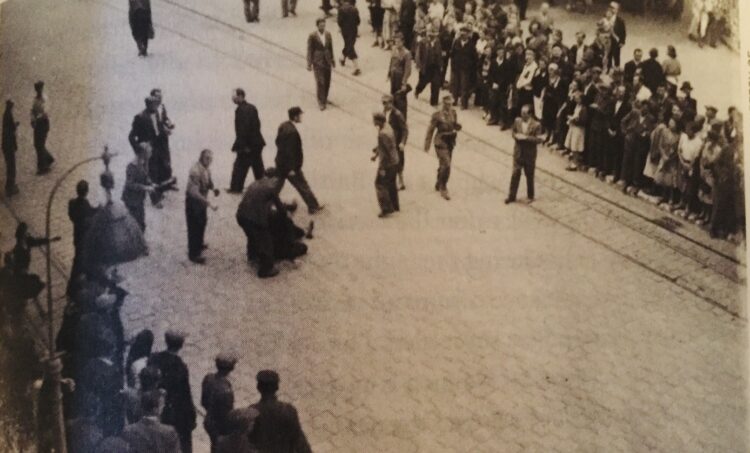

In the wake of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Nazi-instigated pogroms broke out. “The Germans knew that Ukraine had been a site of rabid anti-Jewish violence a generation earlier and believed that they could unleash it once again,” says Veidlinger. In testing the “potency of the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism in Ukraine,” he says, the Nazi accusation “landed on fertile soil.”

A new wave of bloodshed boiled over in eastern Galicia, just as it had in 1918, and multitudes of Jews were slaughtered. In the city of Lviv, thousands were killed. “The Germans referred to the whole episode as ‘Petliura Days,’ signifying an opportunity for Ukrainians to get back at Jews for the crimes of the Bolsheviks, for what they portrayed as the Jewish betrayal of the Ukrainian nation, and for Schwarzbard’s assassination of the Ukrainian leader,” says Veidlinger.

By the autumn of 1943, the Jewish death toll had reached almost 1.4 million. German mobile murder squads, or Einsatzgruppen, were closely involved in the wild killing spree.

“The largest death tolls in Ukraine were recorded in the regions that had once been the Russian provinces of Kyiv, Podilia and Volhynia, followed by the former Austrian province of Galicia, the very same places that a suffered most during the pogroms of the civil war.”

The pogroms of 1918-1921 and 1941 onwards underscored a lamentable fact — the value of Jewish life had been completely debased.