Pope Francis I was in the Middle East — Jordan, the Palestinian autonomous areas of the West Bank and Israel — on a pilgrimage this week. It was be his second trip outside Rome since becoming head of the Roman Catholic Church.

To say that the church historically has had a contentious relationship with the Jewish people is an understatement.

For some two millennia, it considered itself the successor to the covenant between the Israelites and God and, as the “new Israel,” the proper heir to the “promised land.”

As well, the Jewish people were seen as having wilfully refused to accept Jesus of Nazareth as the messiah. As such, they were doomed to a diasporic existence, their very lives circumscribed and subject to the mercy of their Christian neighbors.

Clearly, for the church, the rise of Jewish nationalism in the 19th century, with its program of reconstituting a Jewish state in the Land of Israel, was theological anathema.

But the Zionist movement sought allies wherever it could find them, and the founder of the World Zionist Organization, Theodor Herzl, even made entreaties to the Vatican.

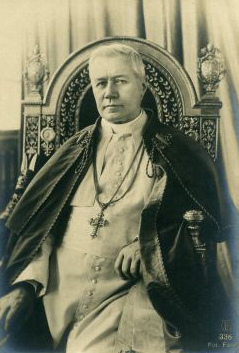

In 1904, he asked Pope Pius X for help in his efforts to establish a modern Jewish state in the historic homeland of the Jewish nation. Pius rejected the request. Herzl was told that “the Jews have not recognised Our Lord, therefore we cannot recognise the Jewish people.”

In 1947, when the UN passed a resolution to partition Palestine into Arab and Jewish states, the Vatican expressed its support for Jerusalem to become a corpus separatum under an international regime.

And when Pope Paul VI visited Israel 50 years ago, he never once uttered the name of the Jewish state, preferring to call it the Holy Land. He avoided meeting with Israeli statesmen.

But things would begin to improve. Nostra Aetate, the “Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions,” was promulgated by the Second Vatican Council in 1965. The document absolved the Jewish people as a whole of deicide: “The Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God,” it asserted.

This theological pivot led to a sea change in church relations with the Jewish state, especially under John Paul II, the Polish pope. In 1985, the State of Israel was for the first time mentioned by name in a public Vatican document, and the Holy See established diplomatic relations with Israel in 1993.

By 2000, John Paul had prayed at the Western Wall, the holiest site in Judaism, and visited the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial. He met with the president, the prime minister and the chief rabbis of Israel.

In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI followed the same itinerary.

In February 2013, a papal conclave elected the Argentinian Jesuit Jorge Mario Bergoglio, archbishop of Buenos Aires, as Benedict’s successor.

As archbishop, the future pope had cultivated closer relations with Argentina’s large Jewish community. He attended Rosh Hashanah services at a synagogue in 2007 and told the congregation that he was there to examine his heart “like a pilgrim, together with you, my elder brothers.”

In 2012 he hosted a Kristallnacht memorial event at the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Cathedral with Rabbi Alejandro Avruj from the NCI-Emanuel World Masorti congregation, commemorating the Nazi destruction of Jewish lives and property in Germany in November 1938.

As Francis I, the pope has followed in the footsteps of his two predecessors. Addressing a delegation from the International Jewish Committee on Interreligious Consultations (IJCIC) in Rome last June, Pope Francis described Nostra Aetate as a “key point of reference” for Catholic relations with the Jewish people.

“A Christian cannot be antisemitic,” he declared, due to “our common roots” with the Jewish people. And he has praised the Jews for remaining faithful to God “despite the awful trials of these last centuries.”

In Jerusalem, Pope Francis laid a wreath on the grave of Theodor Herzl. The symbolism was evident to all.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.