It was one of the most quixotic episodes of World War II, conceived in utter secrecy and ending in abject failure.

On May 10, 1941, Rudolf Hess, Adolf Hitler’s deputy, lowered himself into the cockpit of a twin-engine Messerschmitt aircraft and took off on a flight from Germany to Britain. He hoped his solo “mission of humanity” would end hostilities between Britain and Germany. But much to his disappointment, he was arrested upon landing in Scotland and spent the rest of his life in prison, where, at the age of 93, he committed suicide.

Peter Padfield’s book, Hess, Hitler & Churchill (Icon), traces the origins of Hess’ misguided and naive mission.

Like Hitler, Hess believed that Germany and Britain were natural allies and should join forces to fight a common enemy, the Soviet Union, in order to check communism. There was sympathy for this view in the highest circles in Britain, including the royal family. After abdicating and marrying the American divorcee Wallis Simpson, the Duke of Windsor accepted an invitation to visit Germany, where he was received by Hitler and other leading figures of the Nazi regime.

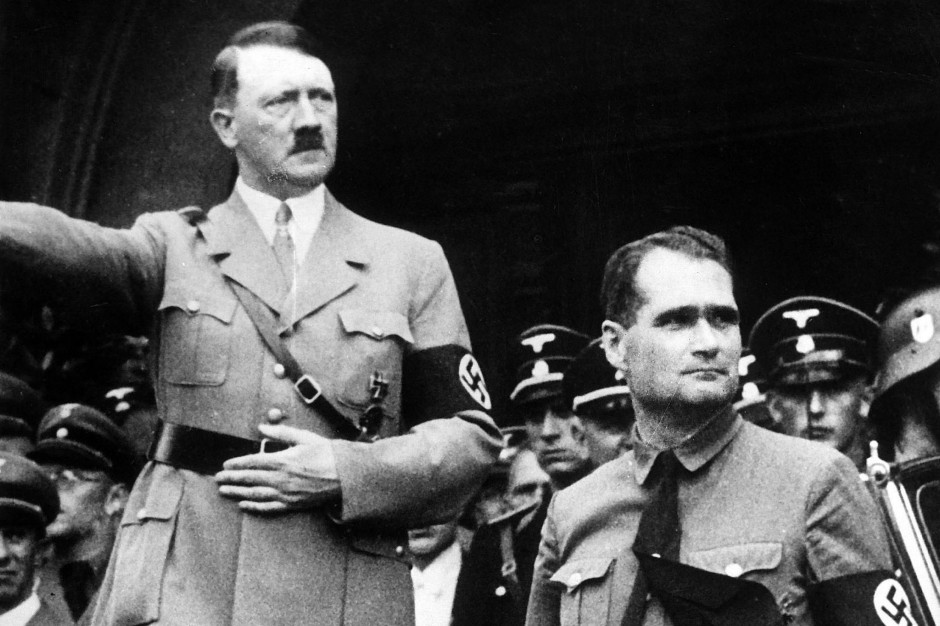

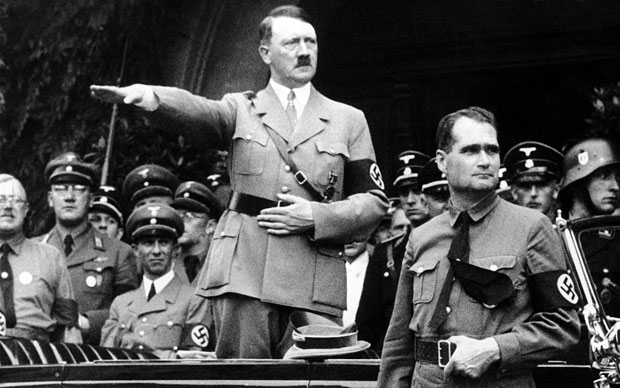

Padfield, a British journalist, describes Hess as a man who loved and adored Hitler. Like Hitler, he was a veteran of World War I who clung to conspiracy theories to explain Germany’s defeat. He first heard Hitler speak in 1920 and was captivated by his oratory. He joined the Nazi party and became one of Hitler’s most devoted aides, buying into his antisemitic policies. (In November 1938, however, he beseeched Hitler to call a halt to Kristallnacht, the nation-wide pogrom that turned out to be a prelude to the Holocaust. Padfield offers no explanation why Hess opposed it).

Shortly after World War II broke out, Hitler delivered a speech in Berlin calling for a rapprochement with Britain. The British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, rejected his appeal, as well as other German peace feelers.

Chamberlain’s successor, Winston Churchill, adamantly opposed the notion of a negotiated peace with Germany. Indeed, he strengthened an edict that permitted the authorities to detain anyone without trial who showed sympathy to an enemy power. The first British citizens to be affected by it were Oswald Mosley, the leader of the British Union of Fascists, and Captain Archibald Maule Ramsay, a Conservative parliamentarian who had founded a pro-fascist club.

Nonetheless, Germany continued its efforts to reach an understanding with Britain. Germany’s terms were clear. If Britain gave Germany a free hand in Europe, Germany would respect British colonial interests in Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

Hess, who agreed with these proposals, dreamed up his peace mission in June 1940, shortly before the momentous Battle of Britain. He made his first attempt to fly to Britain in January 1941, but abandoned it due to mechanical problems.

As he made his final preparations, he wrote a long letter to Hitler explaining his reasons for the flight. Padfield suggests that Hitler may have been privy to his plan. Hess’ wife, Ilse, was kept in the dark.

Hess took off from Augsburg, flew over Bonn and the industrial Ruhr region and headed for the North Sea. His objective was to meet the Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland and an advocate of a British political accommodation with Germany.

After being helped out of his parachute by a farmer, he introduced himself in English as Alfred Horn, saying he had a message for the duke, who lived nearby. He met the duke, disclosing his identity and claiming that Germany had no wish to defeat Britain.

Upon discovering what had happened, Hitler was furious. “Hitler could not afford to be associated with Hess’ mission,” Padfield writes. “Should it fail it would manifest weakness, even desperation …”

After being detained, Hess wrote a mission statement, charging Britain with responsibility for the outbreak of World War I, claiming that Germany would win the war and and urging the British government to make peace now. Citing another source, Padfield says that one of Hess’ proposals revolved around the resettlement of European Jews in Palestine.

At the postwar Nuremberg war crimes trial, Hess was unrepentant, saying he did not want to erase the Nazi period from “my existence.” As he put it, “I am happy to know that I have done my duty to my volk, my duty as a German, as a National Socialist, as a loyal follower of the fuhrer. I regret nothing.”

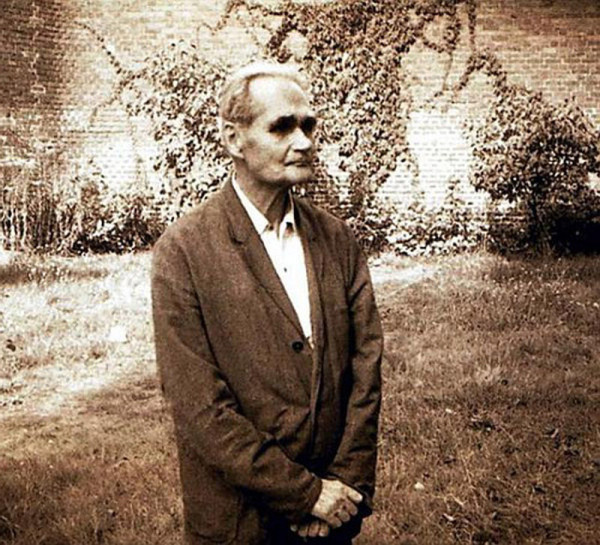

Sentenced to life imprisonment, Hess was consigned to Spandau jail in West Berlin, which the Nazis had used as a collecting point for political prisoners before they were dispatched to concentration camps. Initially, he shared the prison with other Nazis, but eventually, he had it all to himself.

Books and gardening were his chief distractions from boredom and loneliness. He applied for clemency, but the Soviets refused all appeals to release him. In despair, he hanged himself in 1987 from a window latch in the prison garden he so loved.

Padfield tells this story with skill and panache.