Founded in 1866, just a year after the U.S. Civil War ended, the Ku Klux Klan was established as a secret fraternal organization whose aim was to promote white supremacy and reimpose servitude on African Americans by various means of terrorism, including lynchings. Concentrated in southern states that had formed the Confederacy, the Klan faded into obscurity after its African American victims had been disfranchised and economically subjugated.

The second Klan emerged in the early 20th century and reached maturity in the 1920s. It differed significantly from its much smaller predecessor. Officially opposed to violence, operating in the open and stronger in the North than in the South, it added Catholics, Jews and immigrants, among others, to its list of enemies.

Claiming a membership of between four to six million, a figure that may well have been inflated, the Klan elected members to public office and owned or controlled about 150 newspapers and magazines. It was a force to be reckoned with in American society, yet by the mid-1920s, it was on a downward trajectory.

Linda Gordon, a professor of history at New York University, charts its rise and fall in an authoritative and readable book, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition (Liveright Publishing Corporation).

As she says, the Klan attracted a wide range of recruits, from the poorly educated to university graduates and from small merchants and farmers to professionals and wage workers, but its core constituency consisted of lower-middle-class and skilled working-class Americans. Women were also involved, and because they had more disposable time than men, they often spent more hours on Klan work than their male counterparts.

Gordon adds that the Klan’s program, inspired by American nativism and built on ethnocentrism, racism and the politics of resentment, was embraced by millions of Americans who were not even members.

Essentially a mass social movement tapping into discontent, the Klan surfaced against the backdrop of two media events and the lynching of the first and only Jew in American history.

The 1915 film, The Birth of a Nation, adapted from Thomas Dixon’s 1905 novel, The Clansman, portrayed the Klan as defenders of white women threatened by newly freed African slaves. The movie was so popular that President Woodrow Wilson praised it effusively and arranged a screening at the White House, the first time a movie had been shown there.

In the same year, Leo Frank, a Jewish businessman from Atlanta, was falsely accused of the rape and murder of a young white woman, dragged out of his cell and lynched by a racist mob. Five years later, the industrialist Henry Ford published the noxious Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a czarist forgery, in installments in his newspaper, the Dearborn Independent.

Galvanized by The Birth of a Nation and Frank’s lynching, the Atlanta physician William Joseph Simmons decided to create his own fraternal order. Appointing himself Imperial Wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, he recruited a handful of members, several of whom had belonged to the original Klan. Simmons’ outfit experienced little growth until two public relations pros, Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Young Clarke, entered the picture.

Clarke’s father, who had been a Confederate colonel, owned the daily newspaper the Atlanta Constitution. Tyler, climbing up from poverty, achieved wealth and status. The pair, Klan sympathizers and owners of the Southern Publicity Association, convinced Simmons that it had to enlarge its horizons and go after “degenerative” forces destroying the American Anglo-Saxon way of life. Apart from blacks, their enemies were Jews, Catholics and immigrants.

As far as they were concerned, writes Gordon, “only a fusion of racial purity and evangelical Christian morality could save the country.” Which is why the Klan called for an end to non-Nordic immigration and the deportation of non-Nordic Europeans already in the United States. To the Klan, Catholics, Jews, Orthodox Christians, Muslims and people for color could never be truly American.

Melding racism and ethnic bigotry with evangelical Protestant morality and conspiracy theories, the resurrected Klan was launched. By 1920, it had signed up 850,000 new members.

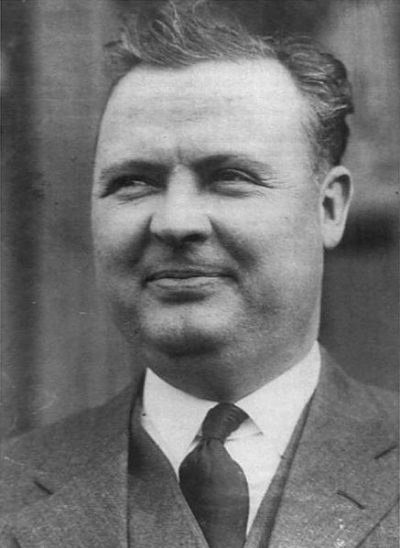

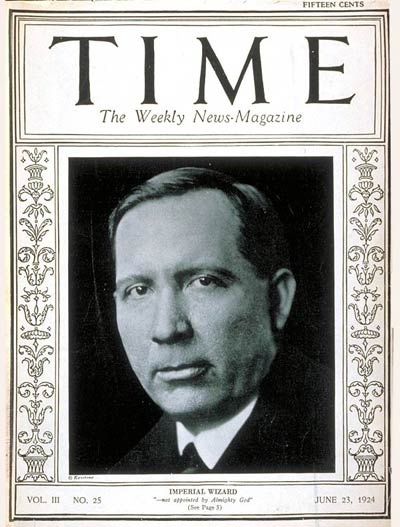

In 1921, Tyler and Clarke and two regional Klan leaders, Hiram Evans of Texas and David Stephenson of Indiana, dumped Simmons and took over the Klan. Evans, a dentist originally from Alabama, became the Imperial Wizard, moved Klan headquarters to Washington, D.C., hired professional speechwriters and attorneys and founded numerous publications.

From the outset, the Klan was antisemitic, contending that Jews posed a threat to American values.

Claiming that Jews were part and parcel of a secular international cabal of financiers planning to seize the American economy, the Klan alleged they produced nothing of value and functioned only as rapacious middlemen, buying and selling.

Through their control of department stores, the garment trade, the media and the Hollywood movie industry, Jews corrupted impressionable minds, the Klan said. Jews were also held responsible for promoting the theory of evolution.

In its haste to condemn Jews, the Klan entangled itself in glaring contradictions. Jews were taken to task both for their inability to assimilate and their propensity for miscegenation. Without much success, the Klan tried to boycott Jewish-owned department stores and Hollywood movies, which were often denounced as corrupters of American morals. It also launched a campaign to get Jews, Catholics and blacks fired from jobs and replaced with “right” employees.

Gordon claims that some of its leaders appeared to soften their attitude toward Jews toward the close of the 1920s, possibly due to the influence of Anglo-Israelism, a late 19th century British sect that holds that Anglo-Saxons are the direct descendants of two of the ten lost tribes of Israel. By contrast, she notes, the Klan “never gave up its hatred for people of color.”

Repulsed by “race mixing,” the Klan fostered prejudice against African Americans, but insisted it did not hate them. Evans wrote that “the Negro is not the menace to Americanism in the same sense that the Jew or the Roman Catholic is a menace.” But as Gordon correctly points out, the Klan’s implicit objective was to keep African Americans in “a servile place with few political and civil rights.”

In Gordon’s estimation, the Klan owed its success to what she describes as “an aggressive, state-of-the-art sales approach to recruitment.” What produced phenomenal growth, at least for a while, were financial incentives, advertisements in the mass media, high-tech spectacular pageants, and exaggerated claims about its size.

Vigilantism strengthened the Klan as well, though such attacks sometimes created enemies. In California’s agricultural belt , she says, it aligned itself with the big growers against farm workers, many of whom were Mexicans.

Readers may be surprised to learn that, up to the mid-20th century, Oregon — a blue liberal state today — was arguably one of the most racist states in the union. Along with Indiana, Oregon shared the dubious distinction of having the highest per capita Klan membership.

During the 1840s, the Oregon Territory banned slavery but also required all African Americans to leave. Until 1959 and 1973 respectively, Oregon refused to ratify the enfranchisement of black males by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. In 1906, the Oregon Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in public facilities was constitutional. Interracial marriage was banned until 1951. In 1893, whites in the town of La Grande burned its Chinatown to the ground. Anti-Japanese feeling was widespread and helped fuel the Klan’s ascendancy. But in the main, Klan efforts were almost exclusively aimed at Catholics, with Jews being a secondary target.

At its height, the Klan was politically influential. Sixteen U.S. senators, 75 congressmen and 11 state governors, nearly equally divided between Republicans and Democrats, were self-declared Klansmen. Probably the most powerful Klansman politician was Albert Johnson of Washington, the chairman of the House Immigration Committee, who spearheaded the drive for immigration restrictions, a Klan priority.

Such was the Klan’s clout that Al Smith, the New York governor, lost his party’s presidential nomination in 1924 simply because he was a Catholic.

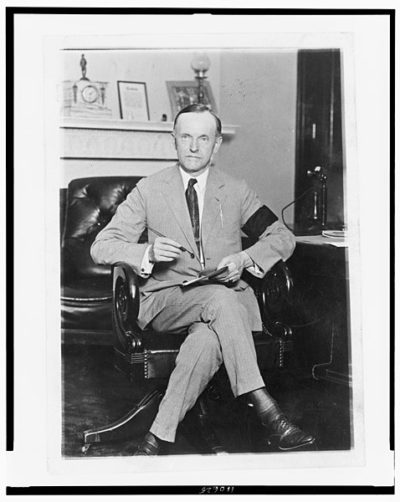

“Neither major political party and none of the presidents in this period — Wilson, Harding, Coolidge and Hoover — could be persuaded to condemn the Ku Klux Klan,” says Gordon in a stunning indictment of the racist political climate in the United States during this era.

The Klan insinuated itself into the judiciary too. Two U.S. Supreme Court justices, Hugo Black and Edward Douglass White, were members of the Klan.

The mayors of two Texas cities, Dallas and Fort Worth, were Klansmen, as were the mayors of Portland, Oregon and Portland, Maine.

By 1927, Klan membership had shrunk to about 350,000. To Gordon, the reasons for its sharp decline are clear. As she puts it, “Leaders’ profiteering — gouging members through dues and the sale of Klan paraphernalia, not to mention criminal embezzlement — grew harder for members to ignore.” Power struggles, which produced splits and even rival Klans under different names, as well as seedy scandals, contributed to its decline.

Above all, the increasing integration of Catholics and Jews into American politics, culture and the economy worked to the Klan’s disadvantage. “The allegedly unassimilable Jews assimilated,” says Gordon. “The alleged vassals of the pope began to behave like other immigrants, firm in their allegiance to America.”

Consequently, the Klan sought out new allies, among whom was the antisemitic Catholic priest Charles Coughlin, whose weekly radio broadcasts reached a gargantuan audience of about 30 million listeners. Some Klansmen also supported the German American Bund, which was supportive of Nazi Germany.

Although the Klan was a spent force by the 1930s, it had been broadly influential in persuading politicians to pass restrictive immigration laws and to impose a climate of intolerance in the workplace. By the 1950s, the second Klan had been replaced by a third wave of Klansmen fighting the civil rights movement in segregationist southern states