Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was in an upbeat mood as he turned up at a press conference in New York City on September 28. One of the topics at hand was his upcoming meeting with India’s newly elected prime minister, Narendra Modi, who’s considered friendly toward Israel.

“We are very excited by the prospects of greater and greater ties with India,” he said. “We think the sky’s the limit. This is an opportunity for Israel and India to expand further our relationship.”

In New York to deliver his annual speech at the United Nations General Assembly, Netanyahu said he planned discuss a wide range of issues with Modi, from bilateral relations to Iran’s nuclear program.

He had reason to be optimistic.

First, this was to be the first meeting between an Israeli and an Indian prime minister in 11 years. The last time that happened was in 2003, when Ariel Sharon, on a state visit to India, met his counterpart, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, in New Delhi.

Second, Modi — the head of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party and the former chief minister of the western province of Gujarat — is keen to upgrade India’s bilateral ties with Israel, as his foreign minister, Sushma Swaraj, who was chairwoman of the Indo-Israel Parliamentary Friendship Group from 2006-2009.

During his 13-year term of office in Gujarat, one of India’s wealthiest provinces, Modi encouraged Israeli entrepreneurs to invest in a vast array of projects from water desalination plants to pharmaceutical factories.

In courting Israeli investors, he visited Israel. While there, he told Israelis that he would return to Israel as prime minister should he win India’s next general election.

No Indian prime minister has ever set foot in Israel, though a succession of Indian cabinet ministers have visited the Jewish state in recent years. It goes without saying that Netanyahu would certainly be pleased if Modi, the leader of the world’s most populous democracy, went to Israel.

Sixteen months before his victory in last May’s election, Modi invited the Israeli ambassador to Gujarat. This prompted an Indian magazine, The Diplomat, to predict that India’s relations with Israel would “expand dramatically” if Modi triumphed in the election.

India’s relations with Israel have developed slowly.

Israel and India officially established diplomatic relations in 1992, when India’s Congress Party governed the country. India, one of 10 countries that voted against the 1947 United Nations Palestine partition plan, recognized Israel only in 1950.

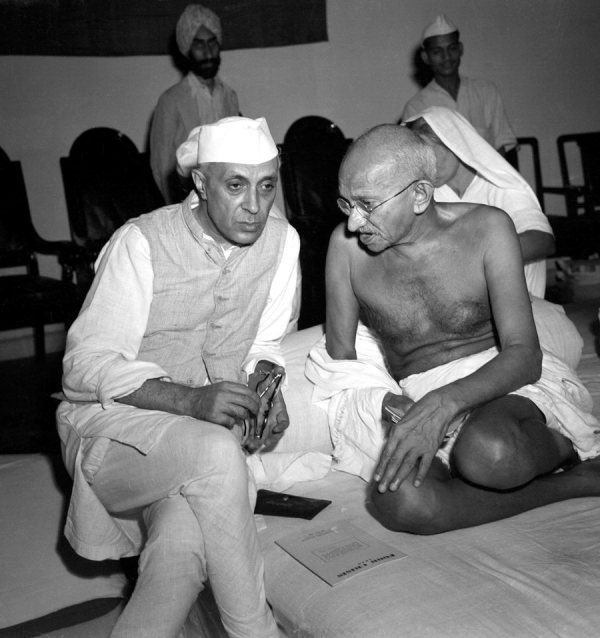

Jawaharlal Nehru, the premier, extended de jure recognition of Israel, but refrained from opening an embassy in Tel Aviv. Israel, however, maintained a trade and consular office in Bombay, now known as Mumbai, where the majority of India’s small community of Jewish citizens live.

India’s decision to boycott Israel diplomatically was not really surprising.

During the British colonial period, Indian secular nationalists from Mahatma Gandhi on down supported the Palestinian cause rather than the Zionist movement. Gandhi, though a foe of antisemitism, was opposed in principle to a Jewish state. The Congress Party, which has ruled India for decades since Indian statehood in 1947, regarded Zionism as a Western imperialist concept.

On a more practical level, India’s stridently pro-Arab position until the early 1990s was a function of three factors. India had to take the pro-Palestinian sympathies of its immense Muslim population into account. India was not only dependent on Arab and Iranian oil supplies, but on the flow of remittances from Indian workers in Arab states.

Also contributing to India’s pro-Arab stance was its membership in the non-aligned bloc, Nehru’s friendship with Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser and Israel’s alliance with the United States, which many Indians disliked.

India’s lukewarm position toward Israel underwent a sea change following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, its ally, and the subsequent end of the Cold War. The Madrid peace conference was a factor in this historic process, as was India’s seminal move to liberalize its state-controlled economy and improve links with the United States.

The rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party was a factor in India’s rapprochement with Israel, too. The party, which administered India from 1996 to 2004, was not as sensitive to Muslim opinion as the Congress Party.

In 2002, communal riots rocked Gujarat, claiming the lives of about 1,200 Indian Muslims. Modi, Gujarat’s top government official, was blamed for turning a blind eye to the massacres. A Supreme Court ruling in 2012 absolved him of complicity in their deaths, but Modi was treated as a pariah by the United States and other Western nations.

Under the leadership of the Bharayiya Janata Party, India’s relations with Israel have flourished.

Two-way trade increased from $200 million in 1992 to $6 billion last year. Israel’s key non-military exports include polished diamonds and telecommunication equipment. India’s main exports run the gamut from uncut diamonds to textiles.

The arms trade is a particularly important component of India’s economic relationship with Israel. Israel is one of India’s biggest suppliers, and among the products India has bought in recent years has been the Phalcon and Green Pine radar systems, Dvora patrol boats, unmanned drones and Python air-to-air missiles.

India, a nuclear power, has partnered with Israel in high-level security cooperation — given Israel’s expertise in this area, India’s tense relations with neighboring Pakistan and the spate of terrorist attacks that have shaken India in the past decade. In 2008, Muslim terrorists from Pakistan attacked a five-star hotel and the Chabad center in Mumbai, killing scores of people.

Israel and India have also enjoyed cooperation in agriculture, water management, high-tech and cyber defence.

India’s growing ties with Israel notwithstanding, India has usually voted with the Arab bloc at the United Nations and remains critical of Israeli settlement construction in the West Bank.

It’s still to early to tell whether Modi will make good on his promise to upgrade relations with Israel. After all, India has vital interests in the Arab world as well as in Iran, whose annual volume of trade with India stood at $15 billion in 2013.

But things have already begun to change. Last summer, with Modi in charge of foreign relations, India was strictly neutral as Israel and radical Palestinian factions fought a 50-day border war in the Gaza Strip.

To Netanyahu, that was a sign of progress.