The distinguished Canadian painter Lawren Harris (1885-1970) was of the view that the purpose of art is to bring people to a state of ecstasy. I doubt whether he accomplished this lofty objective, but I’m certain his paintings, particularly his stark landscapes, concentrated minds and elicited admiration.

This occurred to me as I watched Where the Universe Sings: The Spiritual Journey of Lawren Harris, a one-and-a-half-hour documentary by Nancy Lang and Peter Raymont due to open in theaters in Canada on January 27.

Harris, a member of the famous Group of Seven Canadian painters, was a deeply spiritual man who was never satisfied with the status quo. Always striving for self-improvement, he was constantly on the move for what he described as “the summit of his soul.”

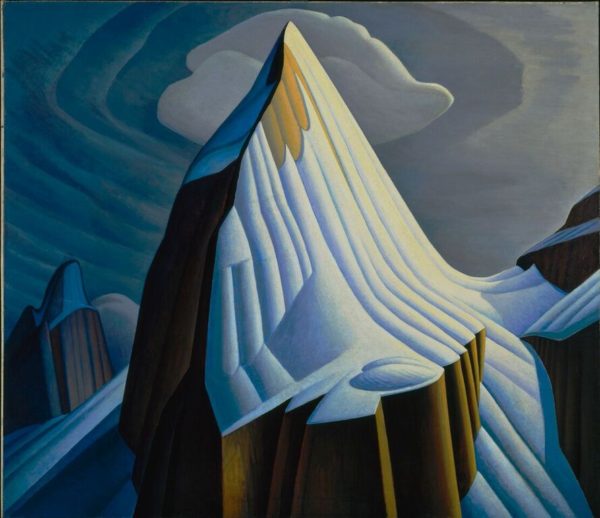

Ever restless, Harris literally climbed mountains to seek out new vistas for his canvas, as this illuminating film illustrates through file footage of spectacular scenery, plausible dramatizations of Harris in search of inspiration and incisive interviews with critics and curators.

Harris, from Brantford, Ontario, was born into great wealth and privilege and could thus afford to pursue his interest in art. Harris’ talent, in the form of doodles, was spotted by a mathematics professor at the University of Toronto, the institution he briefly attended. Thanks to his teacher’s insight and encouragement, Harris spent three years in Berlin learning the painter’s craft and honing his appreciation for nature and landscapes.

Returning to Canada, he married a woman from a rich family and settled into a fine home in Forest Hill, an upscale neighborhood in what was then suburban Toronto.

For reasons which are never explained, Harris began painting vibrant street scenes of a down-at-the-heels district in Toronto inhabited by new immigrants, especially Jews. This was not really his world, says a critic in an understatement.

On a trip to Buffalo, New York, Harris was bowled over by an exhibit of Scandinavian art at the Albright Museum. The light and colors of the winter landscapes that caught his attention left a profound impression on him. He was now determined to be a painter of the Canadian north, which resembled Scandinavia.

Like many young Canadian men of his generation, Harris enlisted in the army during World War I. He emerged unscathed from the killing fields of Europe, but his brother, Howard, was mortally wounded there.

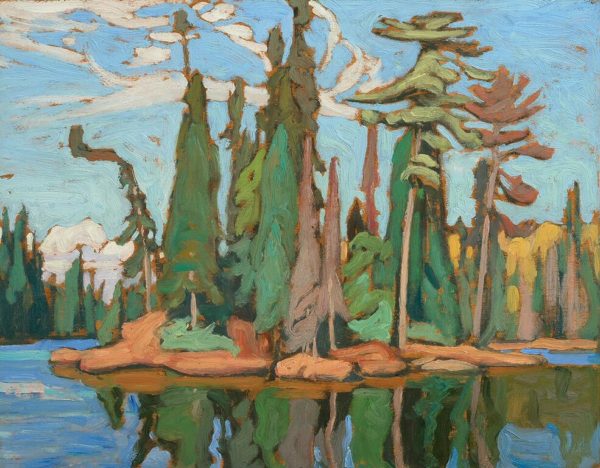

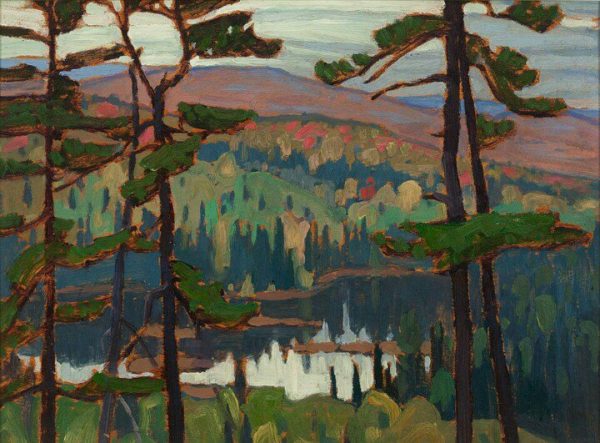

His career took him in new directions after a trip to the Algoma region of Ontario in 1918. He was mesmerized by its pristine lakes, rivers and wooded hills. It was a landscape that spoke to him.

Oddly enough, the film glosses over the formation of the Group of Seven in 1920 and spends far more time on Harris’ mind-bending trip to the north shore of Lake Superior, whose burnished silk waters and dramatic lighting impressed him.

In 1924, he travelled to Jasper Park in Alberta, a trip that had a major influence on his style and color palette. He regarded the crumbling mountains and the glistening glaciers as mysterious and magical. His friend and fellow artist, Emily Carr, recognized the power of his paintings from that period. After visiting his studio, she wrote, “Something has spoken to the very soul of me.”

By then, Harris’ marriage was on the rocks and he was cultivating a relationship with Bess Housser, the woman who would become his soul mate and second wife.

Harris’ fascination with abstract art evolved after visits to art galleries in New York City and a sojourn in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Due to wartime restrictions, he returned to Canada in 1940. He decamped in Vancouver, where he further developed his abstract style and spent the remainder of his life.

Where the Universe Sings paints a well-rounded portrait of a man who left an indelible impression on the Canadian art scene.