Herbert Gildin was one of the lucky ones.

He slipped out of Nazi Germany by the skin of his teeth, finding refuge in neutral Sweden and then the United States.

Whether or not he was a Holocaust survivor in the strictest sense of the word is debatable, but Gildin certainly experienced the savagery of a fascist regime bent on driving Jews out of Germany.

Tyler Gildin tells his grandfather’s story in The Starfish, an engaging documentary available for viewing on the ChaiFlicks streaming service.

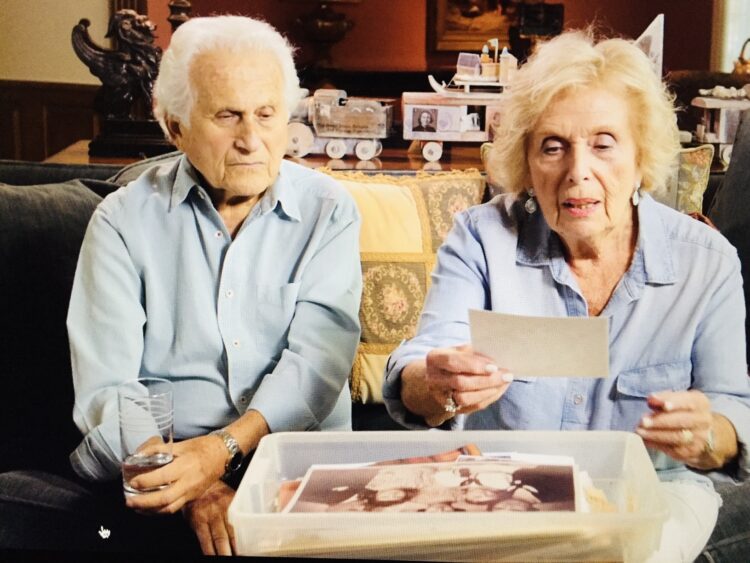

Gildin was 88 years old when he appeared in this film, a father of two grown children, a grandfather many times over, and a successful entrepreneur living in Huntington, New York. “I am happy with what I am today,” he said. “I love the skin I’m in.” But in 1939, at the age of 10, he was a vulnerable Jewish boy without a future.

He and his two sisters, Margaret and Cele, were born in Landsberg, the son of Latvian and Russian immigrants. Thanks to his father’s shoe store, they enjoyed a comfortable bourgeois life. The idyll ended with the Kristallnacht pogroms of 1938. “All of a sudden, we heard breaking glass,” he recalls.

His friends already had begun to shun him, and his father was taken into police custody and advised to leave Germany. Thanks to HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, he and his sisters were able to emigrate. They left Germany about a month after the outbreak of World War II.

They were sent to Sweden, which managed to stay out of the war, and placed with separate Swedish families. Initially, Gildin lived with a childless elderly couple, but that arrangement crumbled because they did not know how to deal with a boy of his age.

He and his next foster parents, the Silows, were compatible. “They were a great, great family,” he says. Gildin connected with their children, learned Swedish, and grew to love Christmas. He also went to church with them. “It was a peaceful, happy existence,” he adds.

In 1940, Gildin’s parents were permitted to enter the United States under the Russian quota. In 1941, Gildin departed from Sweden on what would be a six-week train journey to Japan via Finland and the Soviet Union. From there, he boarded a ship bound for Seattle. And from the west coast, a train took him to New York City to be reunited with his parents.

Skimming over the details, Gildin says he integrated into “the American way of life” with relative ease. He was drafted into the U.S. army in 1951, even though he was not yet an American citizen. He was not shipped abroad and finished his service as a typist on a base in Mississippi.

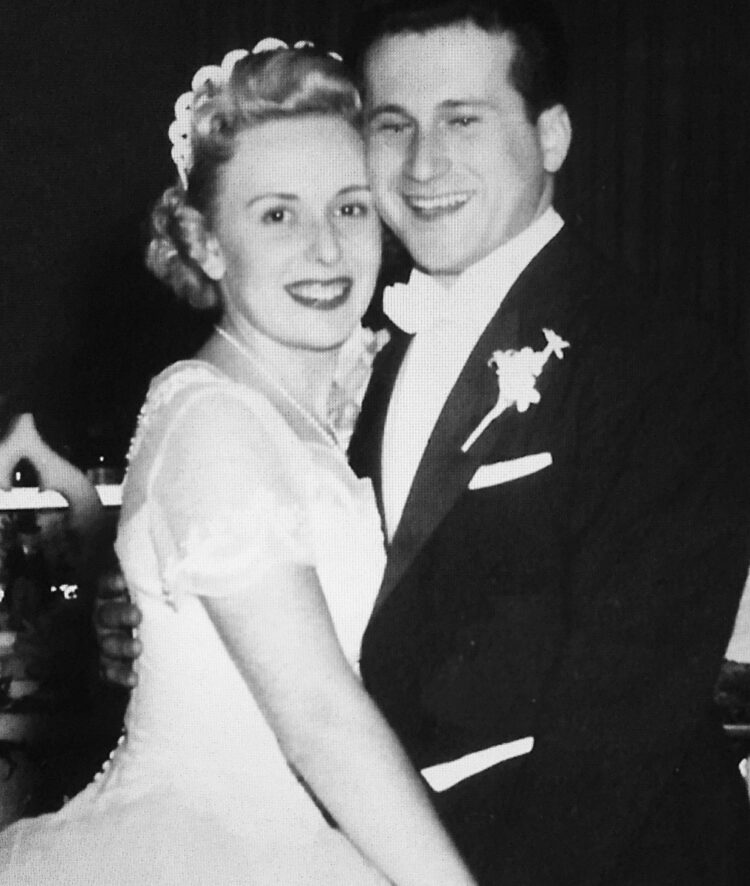

He met his wife-to-be, Gloria, in 1953, and they were married two years later. They had two children.

Lacking professional skills, he bought a partnership in his brother-in-law’s dairy shop in Brooklyn. Disliking the job, he went into the light bulb manufacturing business. “We worked like crazy,” he says. Satco, his company, prospered. Today, it employs more than 350 workers.

In 2001, he returned to Sweden on a sentimental journey and met the Silow girls with whom he shared two years of his life.

Looking back in gratitude, he compares himself to a stranded starfish on a beach that is thrown back in the water by a kind and empathetic boy. He was, of course, thinking of the Swedes who opened up their hearts and home to him and his sisters and made a real difference.