Ten thousand refugees from Germany and Austria settled in the greater Los Angeles area between 1933 and 1941. A significant proportion of the newcomers were Jewish writers, composers, artists, actors and film and theater directors. Among them were Salomea Sara Steuermann, an actress, and her husband, Berthold Viertel, a screenwriter.

They were Nazi Germany’s gift to the United States, a group of creative and accomplished individuals who would enrich American culture for decades to come.

Steuermann, known as Salka Viertel, established herself as a screenwriter, social activist and hostess in Hollywood. She helped launch Greta Garbo as a movie star and assisted emigres regain their footing. Toward the end of her life, she published her memoir, The Kindness of Strangers, a candid account of a bygone era in America’s film capital.

As Donna Rifkind acknowledges in her bracing and exhaustive biography, The Sun and Her Stars: Salka Viertel and Hitler’s Exiles in the Golden Age of Hollywood (Other Press), Viertel has been more or less forgotten since her death. This is what often happens when a person’s career ends on a low note. But in her heyday, during the 1930s and 1940s, she was a fairly substantive figure, though some dismissed and maligned her, as Rifkind points out.

Confident, strong and charismatic, with a gift for friendship, as the British novelist Christopher Isherwood observed, she wielded “a degree of influence” in an industry embittered by “chronic discord, frustration, jealousy and misogyny, both casual and institutional.”

Within a few years of arriving in Los Angeles in 1928 on a visitor’s visa, Viertel formed a fruitful association with Garbo, the reclusive Swedish actress. Garbo appreciated her efforts. “If there was ever any argument about a script, I always had this woman to fight for me,” Garbo said. “She was indefatigable …”

Viertel, an American citizen from 1939 onward, worked with the European Film Fund, which facilitated the immigration of mostly Jewish immigrants into the United States and provided them with the means to survive once they landed there.

And on Sundays, she converted her home on 165 Maybery Road in Santa Monica into a salon drenched in Mitteleuropa ambience. Her guests ranged from the theater director Max Reinhardt and the playwright Berthold Brecht to the actors Johnny Weissmuller and Edward G. Robinson. They enjoyed the lively conversation and the fine home-cooked food and drinks.

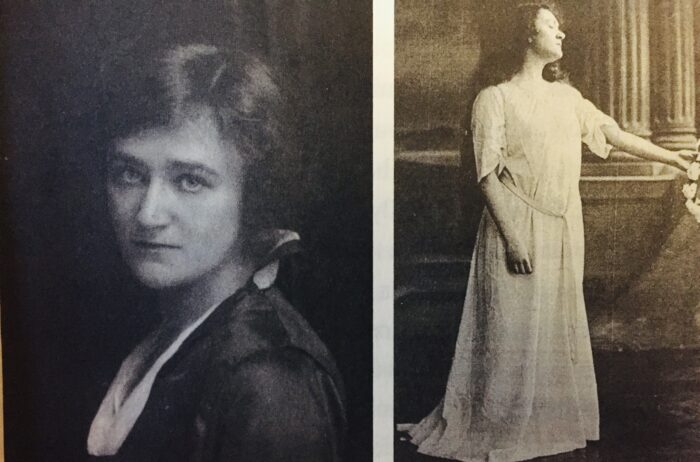

Viertel, born in the Galician town of Sambor in 1889, moved to Berlin to pursue a career in acting. “Never a star and not a classical beauty, she was nonetheless as employable as an actress of her age and station could hope to be,” says Rifkind.

She and Berthold — a poet, essayist, novelist, screenwriter and director whom she would divorce in the late 1940s — formed a repertory company in Berlin in the early 1920s, but due to the hyperinflation plaguing Germany’s economy, they were invariably broke.

In 1927, the German film director F. W. Murnau invited Berthold to be the writer of his next picture. This required him and Viertel to live in Los Angeles. Their plan was to rebuild their finances and return to Germany within four years, but after Hitler’s accession to power, they remained in the United States.

The city that would be their home was a hotbed of antisemitism, targeting, in particular, high-profile Hollywood Jews, who played an instrumental role in the formation of the movie industry. Upon their arrival in Los Angeles, the Viertel’s route took them along Sunset Boulevard, which was rife with for-rent signs on boardinghouses excluding actors, Jews, children and pets. On a more insidious level, antisemitism could be found in real estate covenants and in restricted private schools and country clubs.

The Viertels do not appear to have been affected by this ancient hatred because Hollywood was effectively insulated from it. Berthold, working at the Fox studio, was involved in the production of its last silent movie. The shoot went so well that Fox doubled his salary. Later, at Paramount, he directed four films.

Viertel, meanwhile, appeared in small roles in several German-language versions of American films made between 1929 and 1931. These would be her final performances as a movie actress. Yet her flair for drama lived on in her crowded Sunday afternoon parties on Maybery Road. “She greeted newcomers warmly and got them involved in conversations with earlier arrivals, then she disappeared into the kitchen to see how things were going,” Isherwood wrote.

She had a striking personality, says Rifkind: “Never an obvious beauty, she had learned during her theater days to use every other asset she had — her intelligence most of all, but also her voice and her glance and her gestures — to assume a forceful presence, to make one pay attention.”

Like her husband, Viertel had numerous affairs, some with men much younger than herself.

She met Garbo at a party in 1929 and they bonded. From that point onward, Viertel, her family and friends were Garbo’s anchor in Hollywood. When she negotiated her contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Garbo designated Viertel as the screenwriter of her forthcoming films. From 1933 to 1941, she would be one of the lead writers of Queen Christina, The Painted Veil, Anna Karenina and Two-Faced Woman.

Although Viertel earned a fabulous income during her golden years, she knew she could not expect continuity and stability in Hollywood. At various times, she was arbitrarily sacked, forcing her to retrench, rent out rooms in her home and give drama lessons.

Closely involved with, and financially supportive of, the European Film Fund, Viertel was a lifeline to many emigres, who were closely monitored by the FBI and were required to register as enemy aliens and observe a nightly curfew.

As Rifkind says, she “provided sustenance and support by taking refugees into her home, absorbing them into her social and professional networks, and helping them integrate into American society.”

One of them was the German-Jewish composer Franz Waxman, who would work on 144 films, earn 12 Oscar nominations and win Oscars for Sunset Boulevard and A Place in the Sun.

In addition, she persuaded friends, such as the short story writer Dorothy Parker and the actress Miriam Hopkins, to sponsor refugees.

Viertel brought her mother, Auguste, to the United States in 1941. She was unable to save her brother, Zygmunt, who played for Poland’s national soccer team in the 1920s. He was murdered during the Holocaust, as were the parents of the movie detector Fred Zinnemann.

During the postwar period, the notorious U.S. House of Un-American Activities Committee refrained from summoning Viertel — a liberal and an anti-fascist — for questioning. But due to her friendships with Hollywood personalities who had been regarded as Communists by the FBI, she was considered guilty by association. She avoided the dreaded blacklist, but could not escape J. Edgar Hoover’s unofficial pink list of suspected Communist sympathizers.

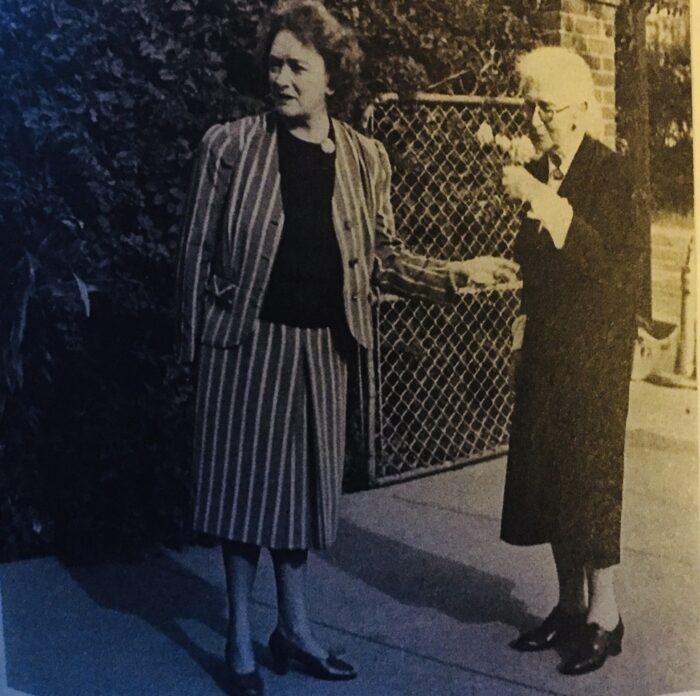

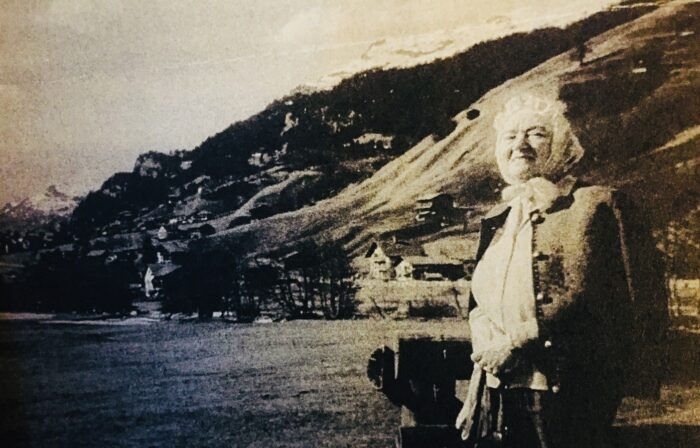

With jobs growing scarcer by the year, Viertel sold her beloved house on Maybery Road and lived in rentals. Finally, she left Los Angeles, bound for the Swiss resort town of Klosters, where she would live for the next 18 years. Garbo would visit her for weeks at a time, but there was generally little for her to do there but read and work on her memoir.

During her waning years, she was beset by poverty, hoping that the book would bail her out of her financial misery. Two major American publishers rejected an outline of her manuscript, but a German publishing house accepted it. The Kindness of Strangers was published in 1969, but there were few reviews and it was out of print within five years.

As she aged, she suffered from a plethora of ailments, forcing one of her three sons to hire a full-time nurse for her. She died in 1978, a half a century after her arrival in Los Angeles. By then, she had long been forgotten by Hollywood’s movers and shakers. Rifkind’s exacting biography brings her back to life in all her glory and permutations.