Klezmer, a Polish film set in Nazi-occupied Poland, exposes viewers to a harsh Darwinian world where life is nasty and brutish.

Streamed by Chaiflicks, an online provider of Jewish-themed and Israeli films, Piotr Chrzan’s dark and pessimistic movie unfolds in a forest near Bialystok in the summer of 1942 or 1943. Polish Jews who have escaped into the woods from a nearby Nazi ghetto are being hunted down by the Germans and their Polish collaborators.

Amid this catastrophe, Michal (Leslaw Zurek), a smuggler who trades or has traded with Jews, and Maryska (Weronika Lewon), an unmarried woman of loose morals, converse in a sunny forest clearing. Michal tells Maryska he intends to settle in Chicago after the war. “In America, you don’t have to be a Jew to make money,” he says in the first of a torrent of antisemitic references, tropes and stereotypes that emerge in this unrelenting film.

As they begin making love in an open field, Michal hears a man’s insistent voice in the distance.

“A Jew,” he shouts.

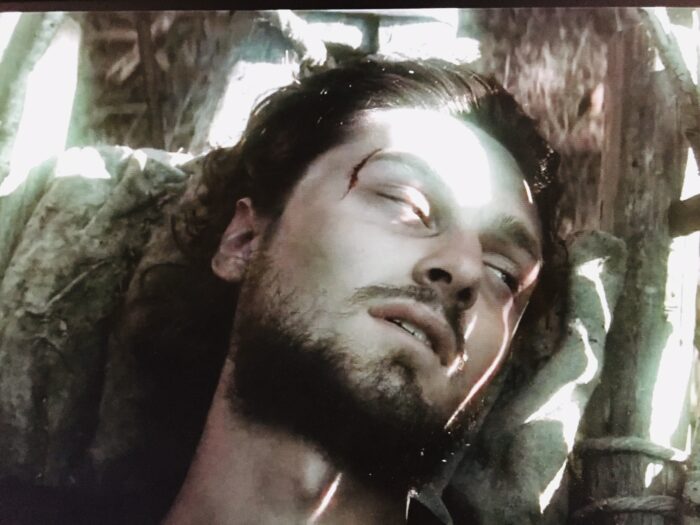

Two Poles, Marek (Szymon Nowak) and Witek (Kamil Przystał), have stumbled upon the injured, half-dead body of a Jewish man who lies prone in a gully. As Michal bends toward him, one of the Poles warns him that Jews are carriers of typhus. “Ignore German propaganda,” counters Michal, who seems to be an open-minded person.

In the ensuing scenes, they launch into a debate as to whether they should turn him over to the village administrator, who will surely betray him to the Germans. If they choose this option, they stand to earn three kilograms of sugar. During their discussions, their primitive, deep-seated antisemitism bubbles to the surface.

“A Jew knows how to hide his money,” says Marek. “He doesn’t show it.” Marek adds that Jews hide gold under their floorboards, but wear shabby clothes to conceal their wealth.

Witek, a simpleton, lashes out at Jews as well. “They live in our country, but won’t help it prosper,” he claims. A little later, he says a priest told him that Jews wear hats to cover their horns.

Maryiska, having decided the Jew should be taken to the administrator, demands a share of the reward. She clearly dislikes Jews. “When Jews were murdering Christ, where was their conscience?” she asks archly.

Chiming in, Marek castigates Jews in a blistering denunciation. “If Jews have money, it’s not theirs. They don’t earn it in an honest way. What a lazy nation. They just sit on their butts and trade.”

Witek’s sister, Hanka (Dorota Kuduk), turns up. Recognizing the Jew, she thinks he’s a fiddler whose name is Dreidl “or something.” Commenting that “Jew music” is very lively, she proceeds to give the Jew, a Christ-like figure, a drink of water and half-heartedly tends to his wounded leg. Although he bats his eyelashes, never once in the film does he utter a word.

Hanka appears to be decent, but her apparent tolerance dissolves when she repeats the medieval antisemitic calumny that Jews kidnap Christians to drink their blood.

“That’s just dumb country folk talk,” counters Marek in an uncharacteristic display of tolerance. Seconds later, he argues that Jews suck the lifeblood out of a country.

Rejoining the conversation, Hanka thinks it would be more profitable to bring the Jew to a Jewish hideout in the forest. Michal blurts out that Jews are envious people and that Hanka’s companion, Rozalka (Ewa Jakubowwicz), could well be Jewish.

As they continue talking, they spy two men whom Michal refers to as bastards. They’re Jew hunters, a despicable class of Poles who earn a living catching Jews for the Germans. One of the hunters says that Jews conceal gold in their stomachs.

Amid the commotion, two more figures show up. They are hard and unfeeling. One is a German soldier, the other is a member of the collaborationist Blue Police. Within minutes, chaos ensues as shots are fired through the dense trees.

Klezmer, released in 2015, unfolds during the course of a single day, leaving an unflattering picture of ordinary Poles coping with adversity, denouncing Jews and trying to survive. There are fine, upstanding Poles in Poland, but they are nowhere to be seen in Klezmer.