Philippe Sands befriended Horst Wachter by chance, but their improbable relationship would be illuminating for both men.

Sands, a professor of international law at University College London, met Wachter, the son of Nazi war criminal Otto Wachter, through Niklas Frank, whose father, Hans Frank, had been the governor-general of German-occupied Poland.

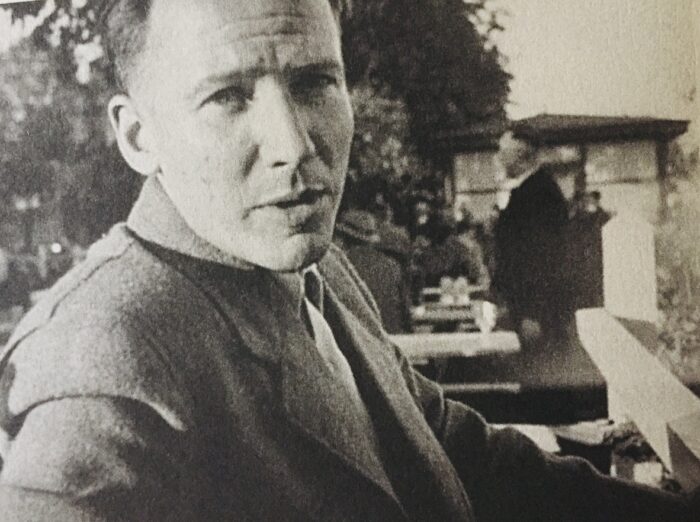

Otto Wachter, one of Frank’s deputies, was a dyed-in-the-wool Nazi. He was involved in the assassination of Austria’s chancellor, Engelbert Dollfus. He was governor of the Polish city of Krakow. He governed Lemberg (Lvov or Lviv), which had been the regional capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And he was instrumental in the creation of the Waffen-SS Galicia Division, composed of pro-Nazi Ukrainians.

Sands’ grandfather, Leon, lived in Lvov, whose Jewish inhabitants were murdered by the Nazis during Wachter’s governorship. After the war, Wachter disappeared.

Niklas Frank, knowing of Sands’ interest in and connection to Lvov, mentioned Wachter and his son, Horst, in one of their conversations. Eager to know what had happened to Wachter, Sands contacted Horst, who was named after Horst Wessel, the composer of a viciously antisemitic song.

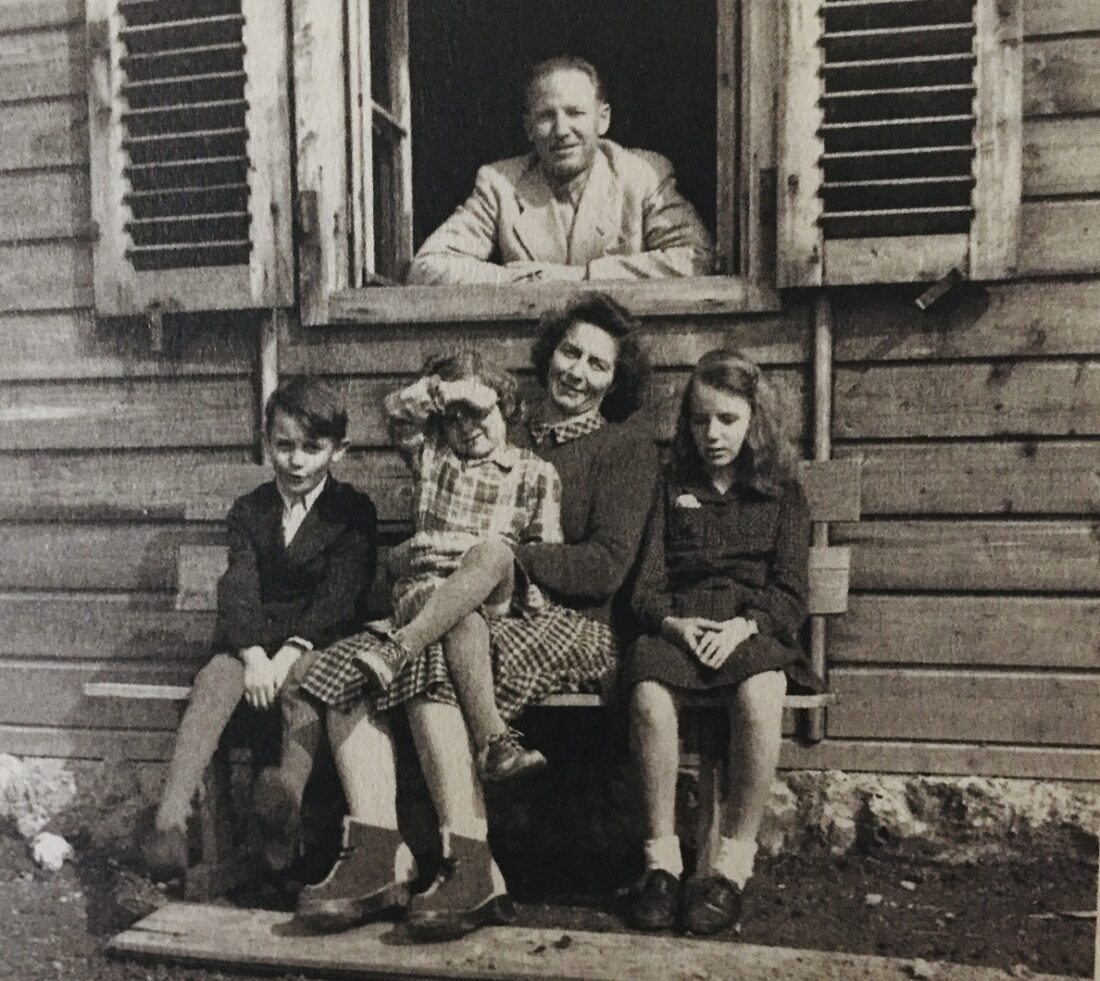

In 2012, Sands visited Horst in Austria. Horst, who was born in 1939, said he had hardly known his father, who was usually away from home during the war years. Yet Horst was convinced he had been a decent man.

“He was unwilling to countenance the idea that Otto Wachter bore any real responsibility for terrible events that occurred on the territory he ruled,” writes Sands in his intriguing book, The Ratline: The Exalted Life and Mysterious Death of a Nazi Fugitive (Alfred A. Knopf). Horst clung to the misguided belief that his father had not committed any crimes in Poland and Ukraine and that he opposed the racial policies of the Nazi regime.

Despite Horst’s far-fetched ideas, Sands liked him because he was gentle and open, with seemingly nothing to hide. Horst’s denials prompted Sands to investigate his father’s career, which comprises the bulk of this thoughtful book.

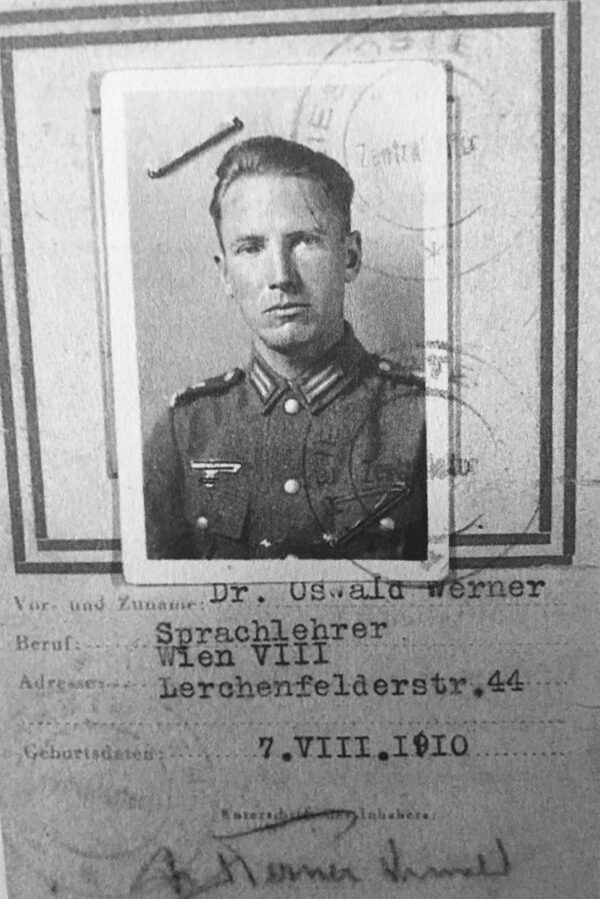

Otto Wachter was born in Vienna in 1901, when his father, Josef, a virulent antisemite, was an officer in the Austrian-Hungarian army. In 1921, he was appointed Austria’s minister of defence.

Otto, a law student at the University ofVienna, inherited Josef’s dislike of Jews. He joined a nationalist club whose platform demanded that Jews be stripped of their basic rights of citizenship and property. After being convicted of participating in an assault against Jewish-owned shops, he was sentenced to 14 days in prison. “Not yet twenty, he crossed the line or criminality for the first time,” writes Sands.

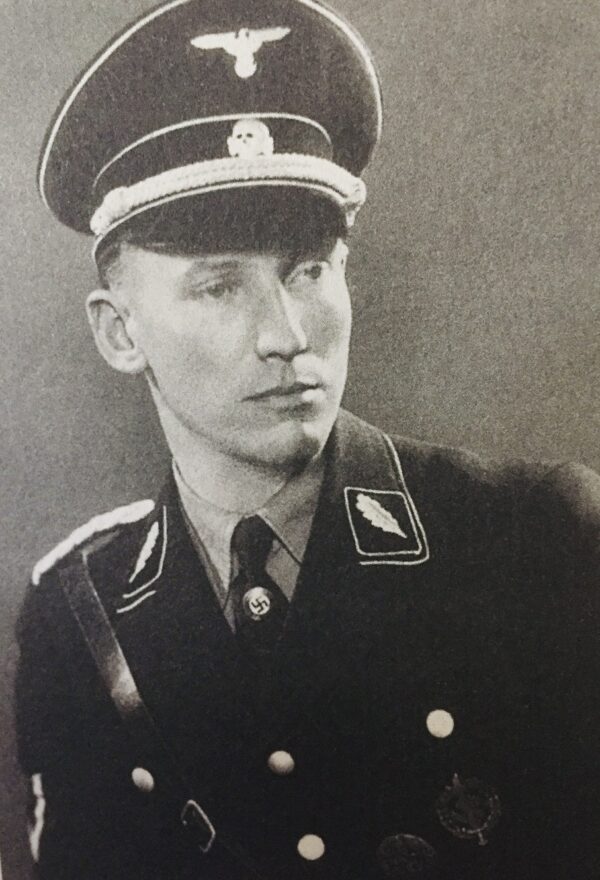

An early supporter of Adolf Hitler, he joined the Austrian branch of the Nationalist Socialist Party. A year before Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, Wachter was inducted into the SS, the paramilitary force that served as Hitler’s praetorian guard. There he made the acquaintance of Heinrich Himmler, who would be the commander of the SS, and his future deputy, Reinhard Heydrich.

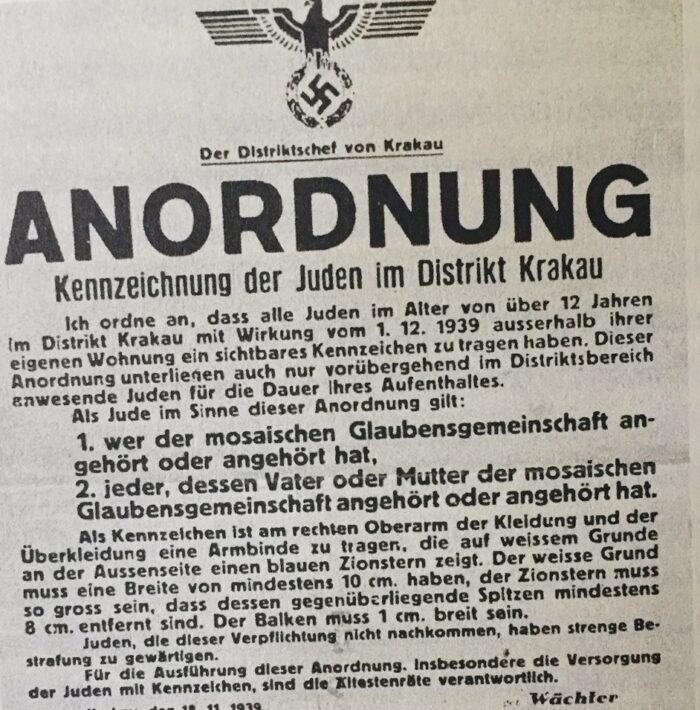

Transferred to Vienna after 1933, Wachter was given the task of removing Jews and politically unreliable personnel from their jobs in the civil service. Having “cleaned” the bureaucracy of undesirable elements, he was assigned to Krakow to serve under Frank. On his first day in office, Wachter ordered the Jews of the city to wear a blue Star of David on a white armband.

Two years later, following the seminal Wannsee conference in Berlin, which targeted the Jews of Europe for destruction, Hitler personally appointed Wachter as governor of Galicia. Shortly afterward, he signed a decree prohibiting Jews from certain professions. This was followed by the roundups of Jews that condemned them to the Belzec extermination camp.

Buoyed by his success in ethnically cleansing Lvov of Jews, and aware that the German army was encountering fierce resistance on the eastern front in the Soviet Union, Wachter persuaded the Nazi regime to form the Galicia Division, the first SS formation composed of non-Germans.

With the Red Army advancing on Lvov, Wachter was sent to Lake Garda, in northern Italy, to head the Wehrmacht’s military administration.

By that point, Germany was on the defensive, but Wachter was certain of “the rightness of our principles” and convinced the war had been ignited by “the eternal subversion of capital and Judaism.” His wife, Charlotte, an ardent Nazi as well, was pessimistic, saying that victory was “no longer possible” because Germany could not defeat “the English, the Americans, the Russians and the Jews.”

As Sands delved deeper into the story, he asked Horst whether he could examine Charlotte’s papers, consisting of letters and postcards. He agreed, thereby enabling Sands to learn more about Wachter during the postwar period.

In the wake of the war, Wachter hid in the mountains of Austria under a new identity while keeping in touch with his family. After an arrest warrant was issued for his arrest, he fled to Rome, where he wrote his memoirs and met Bishop Alois Hudal, an Austrian with pro-Nazi views.

Hudal helped several Nazi war criminals, including Franz Stangl and Josef Mengele, to find sanctuaries in Syria and Argentina by way of the notorious “ratline,” the escape route that enabled thousands of Nazis elude justice.

Wachter hoped that Hudal could assist him in building a new life for himself in South America, but this was not to be, as Sands relates.