Israel and its chief ally, the United States, are squabbling over a variety of contentious issues.

Their strategic relationship is being buffeted by disagreements concerning the Iran nuclear agreement, the expansion of Israel’s settlements in the West Bank, the planned construction of Israeli neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, and Israel’s decision to brand several Palestinian civic and civil rights groups as terrorist organizations.

Tensions have also arisen over Israel’s opposition to the reopening of the U.S. consulate in Jerusalem and China’s involvement in Israeli infrastructure projects.

Last but not least, the United States is piqued that Israeli technology has been deployed by foreign governments to hack the phones of U.S. diplomats and spy on foreign journalists, human rights activists and dissidents.

These challenging issues will test Mike Herzog, the Israeli ambassador to the United States, and Thomas Nides, the U.S. envoy to Israel, both of whom are new to their respective jobs.

Herzog, a retired brigadier general and the brother of Israeli President Isaac Herzog, arrived in Washington on November 15, having replaced Gilad Erdan, a cabinet minister in Benjamin Netanyahu’s previous government.

Nides, a former deputy assistant secretary of state, landed in Israel on November 29. He is replacing David Friedman, a lawyer and business associate of Donald Trump, the former U.S. president.

It took the Biden administration almost 10 months to select Friedman’s successor. During the interregnum, the U.S. embassy was run by the charge d’affaires, Michael Ratney, the former consul general in Jerusalem.

Upon arriving in Washington, Herzog accentuated the positive. “The United States is Israel’s most important ally,” he said, noting that U.S. President Joe Biden is “a true friend” of Israel. “Together, we will work to deepen our cooperation.”

Nides struck a similar tone. “The bonds between our two countries, as President Biden has said, are unbreakable,” he said.

Their comments are a reflection of the unvarnished truth. The United States has no better friend in the Middle East than Israel. And Israel has no better ally than the United States.

But even allies quarrel, and Israel and the United States are no exception to this truism. Over the years, they have clashed intermittently over a multiplicity of issues.

The most immediate point of contention between Israel and the United States today is the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement, or the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Israel, having denounced it since day one, was pleased when Trump pulled out of it in 2018. Like Netanyahu, Trump condemned it as a terrible deal that offered no guarantees that Iran would not morph into a nuclear power in the future.

Biden, Trump’s successor, wants to rejoin and improve the JCPOA. Biden’s goal is to head off a regional war by building a “stronger and longer” agreement that will block Iran’s march toward a nuclear arsenal, defang its ballistic missile capability, and reduce its capacity to assist regional allies such as Hezbollah and Hamas, both of which seek Israel’s destruction.

Israel strongly believes that none of these objectives can be achieved at the talks in Vienna, which are designed to resurrect the JCPOA. These negotiations began last April, resumed late last month after a five-month hiatus, ended on December 3, and are scheduled to resume on December 9.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken is not hopeful that these negotiations can succeed. The United States, he said on December 8, “will not allow Iran to … tread water … and not come forward with any meaningful and serious propositions for resolving the outstanding issues to returning to compliance, while at the same time advancing its program.”

The Israeli government is deeply pessimistic about the talks.

“Israel is very disturbed at what’s happening in Vienna, since reports from the nuclear negotiations in recent days support the early Israeli estimate that Iran will present a very hard line at the talks and will try to delay returning to the agreement’s framework,” writes Israeli commentator Lilach Shoval. “Israel believes Iran is delaying in order to use this time to continue the nuclear program without inspection and to stockpile enough enriched material and knowledge that would enable a quick breakthrough to nuclear power.”

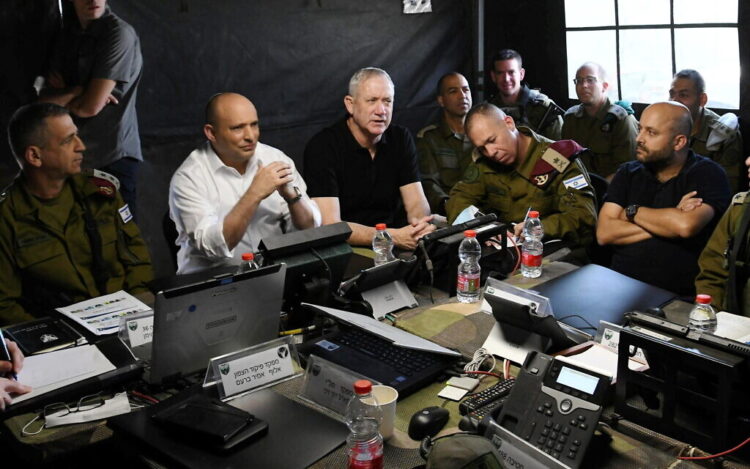

As a result, Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and his colleagues, Defence Minister Benny Gantz and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid, are highly skeptical of Biden’s diplomatic strategy. They are convinced that Iran, having breached the agreement since the U.S. withdrawal, is on the cusp of weaponizing its nuclear program.

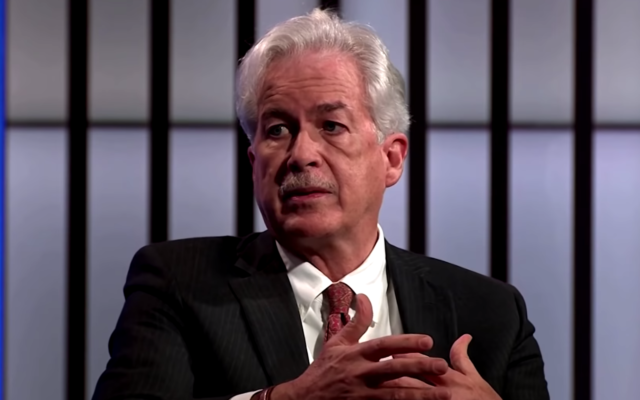

The United States appears to disagree with Israel’s grim assessment. In an interview with The Wall Street Journal, William Burns, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, said he has no evidence that Iran intends to do this.

Israel is convinced that the talks will lead nowhere. On December 2, in a conversation with Blinken, Bennett accused Iran of resorting to “nuclear blackmail” as a negotiation tactic. Urging the United States to pull out of the Vienna talks, he called on the major powers that signed the JCPOA — Russia, China, France, Britain and Germany — to take “concrete steps” against Iran.

Bennett’s blast stood in sharp contrast with his pledge to Biden last August at the White House that he would not wage a public campaign against a possible U.S. return to the JCPOA.

Lapid has adopted a hard line as well, having urged the United States and its Western allies to reinforce its existing sanctions and present “a credible military threat” to deter Iranian nuclear advances.

David Barnea, the director of the Mossad, Israel’s external intelligence agency, has said that Israel will do what it can to thwart Iran’s nuclear ambitions. “Iran will not have nuclear weapons, not in the coming years, not ever,” he said a few days ago. “That is my promise, that is Mossad’s promise.”

Israel has attempted to undermine Iran’s nuclear program by sabotaging its facilities and assassinating its scientists. The United States, however, is far from certain that this tactic has been effective. U.S. officials told The New York Times last month that Israel’s clandestine attacks have only emboldened Iran to upgrade its nuclear infrastructure and enrich uranium to higher levels than permitted under the JCPOA.

Israel and the United States are also at odds over an old and festering issue — Israel’s settlement construction program in the West Bank.

When Bennett — a hawk who opposes Palestinian statehood — assumed the premiership last June, pundits assumed he would concentrate on domestic matters pertaining to the coronavirus pandemic and the economy. The reasoning behind their assumption was that Bennett would not dwell on hot-button issues like the Palestinian question because his right/center/left coalition government is composed of a diverse range of parties with sharply different agendas regarding Israel’s protracted conflict with the Palestinians.

Contrary to expectations, Bennett is trying to consolidate Israel’s grip on the West Bank, which has been occupied by Israel since the Six Day War.

In recent weeks, the Israeli government has announced plans to build several thousand housing units in settlements deep in the West Bank running the gamut from Kedumim and Elon Moreh to Eli and Beit El. Israel claims they are necessary to accommodate “natural growth.”

Israel’s essentially self-serving argument has fallen on deaf ears in Washington. The Biden administration has made it crystal clear that settlement construction undermines the prospect of a two-state solution, to which it is fully committed.

According to reports, Ratney, the U.S. charge d’affaires, had a “difficult” conversation with Bennett’s senior policy advisor, Shimrit Meir, over settlements. Blinken called Gantz to complain, while Ned Price, the State Department spokesman, issued a condemnation. “We strongly oppose the expansion of settlements, which is completely inconsistent with efforts to lower tensions and restore calm,” he said. “And it damages the prospects for a two-state solution.”

A few days ago, Blinken phoned Bennett to express dismay over Israel’s plan to build 9,000 housing units in Atarot, the site of an abandoned airport in Jerusalem. Stung by Blinken’s reaction, Israel has reportedly delayed the project by a year, but has not taken it off the table.

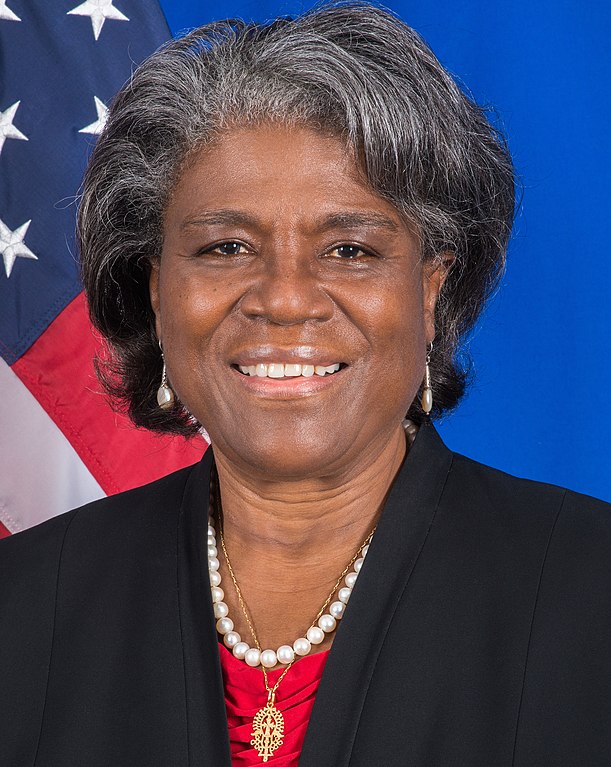

The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, who visited Israel last month, noted that the United States’ disapproval of settlements goes back decades. “This is nothing new for us,” she said. “But the practice has reached a critical juncture, and is now undermining even the very viability of a negotiated two-state solution.”

Gantz’s recent decision to designate six Palestinian civic and civil rights groups in the West Bank as terrorist organizations with connections to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine has sown further tension.

Gantz assumed that the United States would not object to this designation after he announced a series of measures to strengthen the Palestinian Authority and ease conditions in the West Bank.

But in a tacit rebuke, Price, the State Department spokesman, said, “We believe respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms and a strong civil society are critically important to responsible and responsive governance.”

And in light of Israel’s refusal to release evidence regarding its accusation, Price said he would “be engaging our Israeli partners for more information regarding the basis for these designations.”

Last May, Biden announced that Israel would reopen its consulate in Jerusalem, which has served the needs of Palestinians from East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip since the Six Day War.

The consulate was folded into the U.S. embassy by the Trump administration in 2018, a year after it officially recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and moved the embassy in Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

Bennett opposes this plan on the grounds that the reopening of the consulate would cast doubt on Israel’s claim to East Jerusalem, which it annexed in 1967.

“There is no place for an American consulate that serves the Palestinians in Jerusalem,” he said. “This has been conveyed to Washington both by myself and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid. We are expressing our position consistently, quietly and without drama, and I hope it is understood. Jerusalem is the capital of Israel alone.”

Lapid has delivered the same message. “If the Americans want to open a consulate in Ramallah, we have no problem with that,” he said. “But sovereignty in Jerusalem belongs to one country — Israel.”

It remains to be seen whether the Biden administration will actively challenge Israel on this potentially explosive issue.

Israel’s relations with China poses another problem for the United States. Since Netanyahu’s meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2017 and Chinese Vice-President Wang Qishan’s visit to Israel a year later, Israel and China have upgraded their economic ties considerably.

A Chinese company is currently constructing a light rail line in Tel Aviv. And in Haifa, China recently finished building a private port. The United States fears that a Chinese presence in Haifa will enable China to monitor movements of its naval forces in the Mediterranean Sea, thereby endangering its interests in the region.

For years now, Washington has warned Israel to be wary of Chinese infrastructure projects. The Trump administration intensified pressure on Israel with respect to this issue. Biden has adopted this policy. Washington wants Israel to modify its procedures on foreign investments, and while the Israeli government is respectful of American sensitivities, it has its own red lines to consider.

The United States has pressed Israel on other aspects of the China file. Bowing to a U.S. demand, Israel recently joined 40 other countries calling on China to grant independent observers access to the Xinjiang region, the ancestral home of the persecuted Muslim Uyghur minority. Israel, however, declined to sign a United Nations statement expressing concern over China’s treatment of the Uyghurs.

Last month, the Biden administration blacklisted the NSO Group, an Israeli surveillance firm whose Pegasus spyware has been purchased by foreign governments to repress dissent and conduct espionage missions. In one of these operations, the smart phones of 11 U.S. diplomats in Uganda were compromised.

Following U.S. complaints, Israel’s Ministry of Defence imposed restrictions on the export of cyber warfare technology. NSO claims that its products are used to combat terrorism and criminal activity.

Since this software can be utilized for darker purposes, Israel will have to exercise greater vigilance to ensure that this advanced technology does not fall into the wrong hands and damages its already frayed bilateral relations with the United States.