From 1933 until 1945, a momentous 12-year period encompassing the rise and fall of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime and the onset of the Holocaust, the United States admitted 225,000 European Jewish refugees. This was more than any other country, but only a fraction of the Jews in jeopardy who clamored to find a safe haven in America during these perilous times.

“America’s ‘golden door’ was not wide open,” says Gunther (Guy) Stern, a German Jew who arrived in the United States in 1937 without his family.

The United States’ ambivalence, rooted in nativism, xenophobia and antisemitism, is methodically and heartbreakingly explored in three two-hour episodes of The U.S. and the Holocaust, which will be broadcast by the PBS network on September 18, 19 and 20 from 8 to 10 p.m. ET (check local listings).

Partially inspired by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Americans and the Holocaust exhibition, this ambitious documentary is directed and produced by Ken Burns, Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein and written by Geoffrey Ward. Combining commentaries by historians with first-person accounts by Holocaust survivors, it is erudite, passionate and sweeping in scope.

Until the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, virtually anyone from anywhere could immigrate to America’s shores. Prior to the U.S. Civil War, most new immigrants hailed from Britain, Ireland, Germany and Scandinavia. But of the nearly 25 million immigrants who streamed into the United States from 1870 to 1914, the vast majority were from eastern and southern Europe.

Among the new immigrants were two million Jews fleeing persecution and pogroms in the Russian empire. By 1910, New York City was home to one million Jews, the world’s greatest urban concentration of Jews. Many lived in crumbling tenements on the Lower East Side, a teeming, colorful neighborhood.

There was an inevitable backlash. Many old stock white Protestant Americans feared they would be swamped and “replaced” by the newcomers, who often did not share their language, religion, culture and, perhaps, their values.

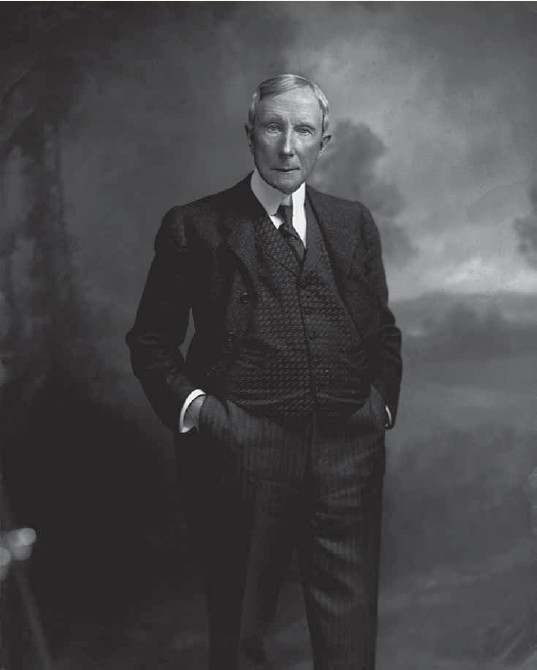

Americans who felt superior to these immigrants were swept up by the new eugenics movement, which classified races and ethnic groups in a hierarchical order based on national origins. It was supported by, among others, the politician Theodore Roosevelt, the financier John D. Rockefeller and the industrialist Andrew Carnegie, all members of America’s elite.

In short order, 33 of 48 states passed eugenics laws to sterilize the racially “unfit.” The last of these racist statutes was not abolished until 2015.

Madison Grant, a renowned conservationist and the author of The Passing of the Great Race, was in the forefront of this popular nation-wide movement. For Grant, a dyed-in-the-wool antisemite, Jews were uncouth Asiatics.

Antisemitism in the United States intensified in the opening decades of the 20th century.

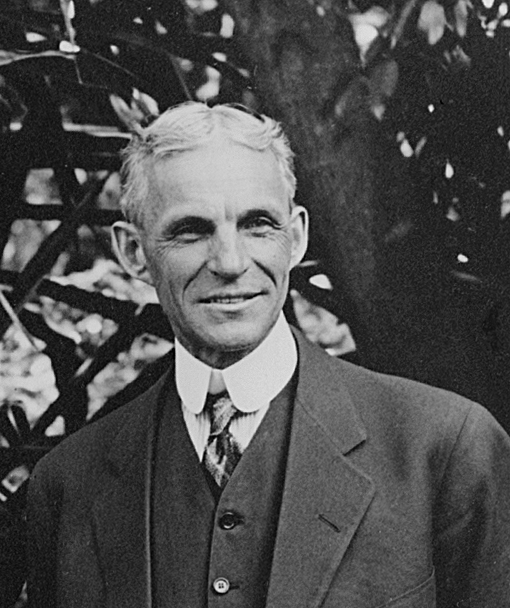

Henry Ford, the car manufacturer, was among its most vocal proponents. In his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, he ran excerpts from the infamous czarist forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

The Ku Klux Klan, which had dwindled into obscurity in the late 19th century, reemerged with a vengeance in the 1920s.

Given these ethnocentric trends, the U.S. Congress passed the restrictive Johnson Reid Act in 1924 drastically limiting immigration from all corners of the globe except northern Europe. With the onset of the Depression in 1929, anti-immigrant sentiment swelled.

In 1932, for the first time in American history, more people left than entered the United States.

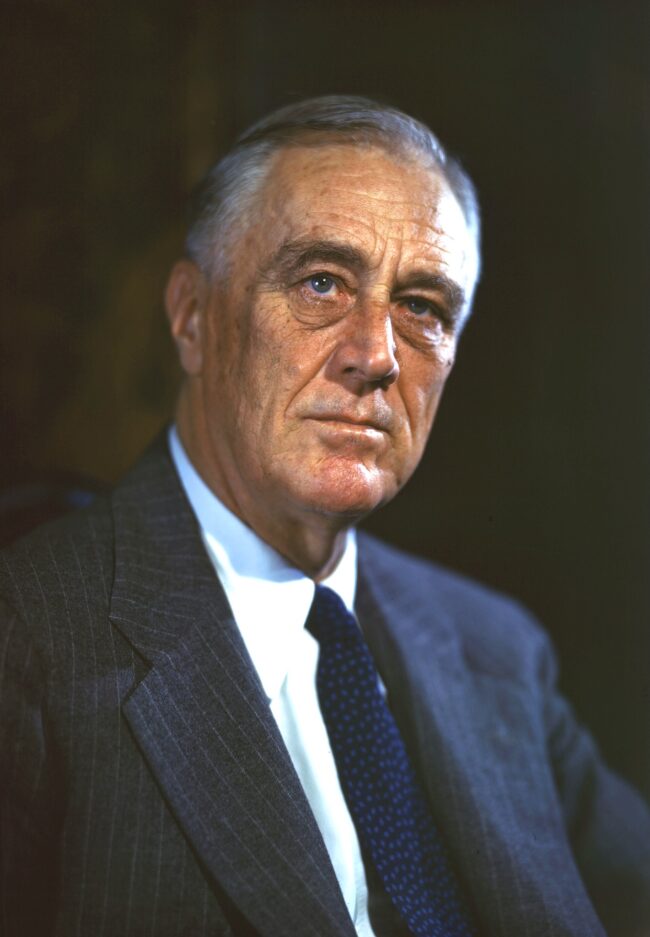

The U.S. State Department, a bastion of conservatism, endorsed America’s biased immigration policy. President Franklin D. Roosevelt loathed the Nazi regime in Germany, but he was not politically free to admit Jewish refugees on a limitless basis. His secretary of state, Cordell Hull, naively claimed that Germany’s persecution of its Jewish citizens would cease if American Jews curbed their participation in anti-Nazi demonstrations. During this era, antisemitic organizations, ranging from the Silver Legion to the Friends of the New Germany, proliferated.

As one historian observes, Germany’s anti-Jewish laws were inspired by America’s Jim Crow segregationist legislation.

U.S. corporations, including Hollywood movie studios, continued doing business with Germany, even as it imposed tighter restrictions on Jews.

Roosevelt, in 1938, tried to ease the immigration quota for Jewish refugees, but U.S. public opinion was strongly opposed. Judging by one poll, two-thirds of Americans thought that Jews were partly or wholly responsible for antisemitism.

At the close of the 1930s, Otto Frank — a German Jew who had fled to Holland with his family — applied for a U.S. entry visa. He never received it because the German Air Force bombed the U.S. consulate in Rotterdam, destroying it and its documents.

* * *

The second episode begins as the Kristallnacht pogrom sweeps through Germany in November 1938. Although the overwhelming majority of Americans unequivocally disapproved of it, seventy percent voiced opposition to loosening immigration restrictions so that German Jewish refugees could settle in the United States.

Robert Reynolds, a U.S. senator from North Carolina, spoke for many Americans when he said he was in favor of building a high and secure wall to keep “alien or foreign refugees” out of the country.

Roosevelt was so outraged by Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, that he recalled the U.S. ambassador in Berlin and permitted visiting German Jews with tourist visas to remain in the United States. Roosevelt, however, was powerless to change the infamous immigration quota system, which kept Jewish refugees at bay.

Only Congress possessed that power and it supported the status quo. In the winter of 1939, two of its members submitted a bill to allow 10,000 Jewish children into the United States, but patriotic organizations like the Daughters of the American Revolution opposed it, forcing its sponsors to withdraw it.

“It was very difficult to get a visa,” says Sol Messinger, a German Jew of Polish descent who eventually made it to the U.S.

In the spring of 1939, his parents acquired a Cuban visa and, along with more than 900 Jews, set sail for that Caribbean island aboard the German ship St. Louis. Only 28 of the passengers were permitted to disembark in Havana. The St. Louis headed toward Florida, but the U.S. State Department decreed that the passengers could not be admitted without visas, a time-consuming process. Ultimately, the refugees found sanctuaries in several Western European countries, but 254 were murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

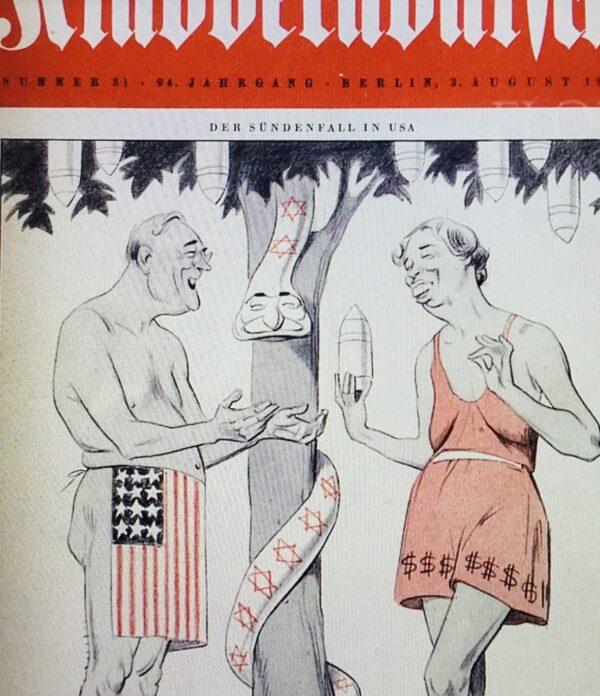

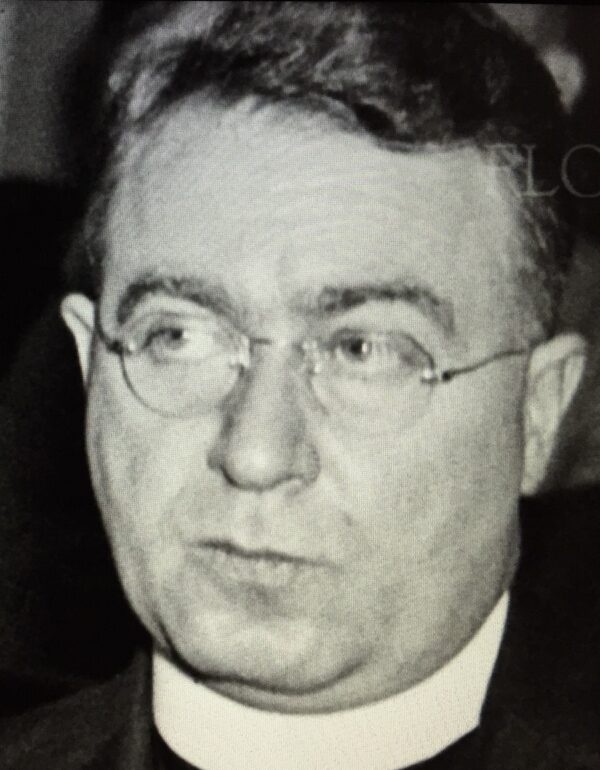

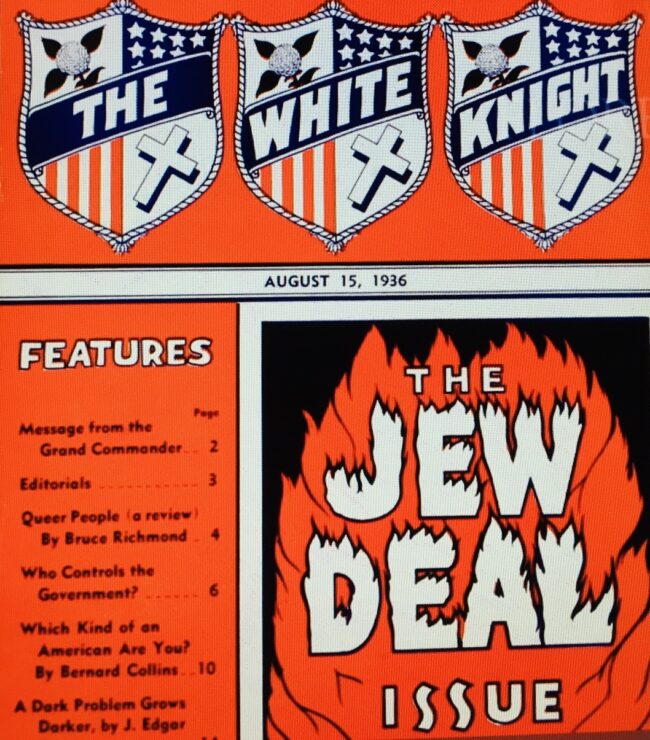

Before and after the St. Louis incident, outspoken antisemites, such as Father Charles Coughlin, falsely claimed that American Jewish businessmen were firing workers and replacing them with Jewish refugees. The German American Bund, a pro-Nazi group, railed against Jews and contemptuously referred to Roosevelt as Rosenfeld and the New Deal as the Jew Deal, in line with German propaganda.

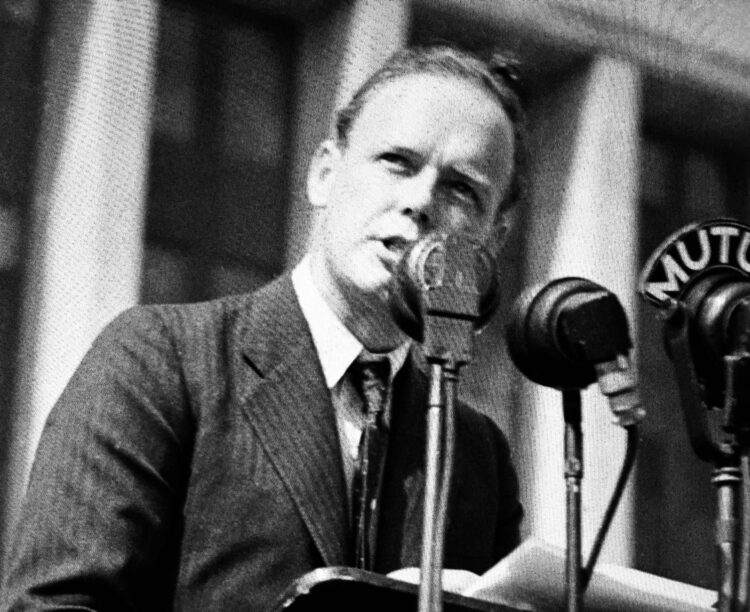

At a moment when America was in the grip of isolationism, one of its chief proponents, the national hero Charles Lindbergh, urged Roosevelt to hew to a policy of neutrality. The president was not inclined to follow his advice. On his recommendation, Congress lifted the U.S. arms embargo, and Britain and France were permitted to purchase weapons. Later on, Roosevelt pushed through the Lend Lease Act, which channelled military equipment to Allied powers in Europe.

Lindbergh, an admirer of Germany’s Nazi regime, sullied his reputation when, in a notorious speech in 1941, he blamed Congress, Britain and American Jews for trying to drag the U.S. into a war with Germany. In his diary, he wrote that, while a small number of Jews added “character” to a nation, too many Jews created chaos. As far as Roosevelt was privately concerned, Lindbergh was a Nazi.

Appalled by the mistreatment of Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe, Roosevelt pressed Latin American nations to accept some 40,000 Jewish refugees. But many Americans were under the impression that refugees could easily be turned into spies by Germany. Breckenridge Long, a U.S. official in charge of the State Department’s visa section, held fast to this belief. “Fear of spies intersected with antisemitism,” says historian Deborah Lipstadt.

Liberals like the writer Varian Fry resisted this trend. A key member of the Emergency Rescue Committee, he was sent to Europe to assist Jewish refugees in southern France. Working in tandem with the U.S. consul in Marseille, Hiram Bingham, he rescued about 2,000 Jews, some of whom had attained fame as artists and intellectuals. Highly skeptical of his activities, Cordell Hull urged the French Vichy regime to expel Fry.

Much of this episode deals with the Holocaust as it unfolded in the Soviet Union following Germany’s invasion on June 22, 1941. Einsatzgruppen mobile killing squads murdered thousands of Russian Jews per day. According to historian Peter Hayes, three-quarters of all Holocaust victims were killed within a 20-month span.

The Wannsee conference, which laid the groundwork for the systematic extermination of European Jews, took place in Berlin on January 20, 1942. It is examined at some length.

* * *

The third and last episode begins as Germany bans Jewish emigration in October 1941 and the Roosevelt administration learns the Nazi regime is engaged in a no-holds-barred war of genocide against Jews. Jewish leaders beseeched Roosevelt to do something. He replied that an Allied victory was the best way forward.

This segment unfolds against the backdrop of the Holocaust throughout Nazi-occupied Europe.

In Amsterdam, the Frank family huddled in a secret annex. Anne Frank wrote in her diary, “I’m terrified our hiding place will be discovered and I’ll be shot.” In extermination camps like Aushwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek, the Nazis began using Zyklon-B gas an an efficient method of murdering Jews en masse.

A German industrialist alienated from the Nazi regime informed Gerhard Riegner, a World Jewish Congress official based in Switzerland, that Germany intended to escalate its genocidal campaign against Jews. Riegner’s report was suppressed by the U.S. State Department, but its explosive contents were leaked to the American media.

Rabbi Stephen Wise, an American Jewish leader close to Roosevelt, pleaded with him to help. Less than two weeks later, the United States and Britain issued a strong statement condemning Germany’s bestial policies and promising vengeance. But neither Washington nor London took practical measures to save Jews imperilled by Germany. A Gallup poll published in 1943 reported that fewer than half of respondents believed the atrocity stories coming out of Europe.

Jan Karski, a courier from the Polish underground very familiar with events in Nazi-occupied Poland, met Roosevelt in 1943 to apprise him of the dire situation. Roosevelt assured him that justice would prevail. Felix Frankfurter, a Jewish Supreme Court judge, confessed he was unable to believe Karski’s chilling account.

Four hundred mostly Orthodox rabbis marched to Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. to publicize the plight of European Jews. Although Roosevelt declined to see them, they were granted an audience with Vice President Henry Wallace. Several Congressmen called for a commission to study the problem, but the U.S. State Department vetoed their proposal.

“Obstructions were thrown in the way,” says John Pehle, a U.S. government official sympathetic to Jewish concerns. “It’s as simple as that.”

Roosevelt’s only Jewish cabinet minister, Secretary of Treasury Henry Morgenthau, confronted Hull and Long and then discussed the matter with Roosevelt himself.

On January 22, 1944, Roosevelt authorized the establishment of the War Refugee Board, whose mandate was to assist Jews caught in the Nazi vise. Pehle, an American of German descent, was appointed its director. “It dramatically changed the policy of the United States overnight,” he says.

The War Refugee Board was most effective in Hungary, where some 400,000 Jews had been deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau by the pro-Nazi regime headed by Nicholas Horthy. The humanitarian mission carried out by the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest was partially financed by the board.

By the close of the war, seven out of ten Americans supported the admission of refugees to the United States. Nevertheless, the U.S.’ immigration quota system remained firmly in place.

Pehle, as well as Jewish leaders, recommended the bombing of Auschwitz-Birkenau and the rail lines leading to it, but John McCloy, the assistant secretary of war, claimed that such air raids would be pointless.

In 1945, American troops liberated several Nazi concentration camps, but the U.S. did not abolish its discriminatory quota system until 1965.

As The U.S. and the Holocaust states, the United States fell lamentably short of its democratic ideals during the 1930s and 1940s.