A “white crow” in Russian is a reference to an unusual person or an outsider. This appellation was certainly applicable to the late Russian ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev. A non-conformist, he was brash and outspoken, straddling the thin line between the permissible and the unacceptable.

Although he achieved recognition and fame as one of Russia’s greatest dancers, he felt stifled in the conformist atmosphere of the Soviet Union. In 1961, when he was 23 and already a star performer in the Kirov Ballet, he defected to the West, enraging and embarrassing the Soviet government. Nureyev’s headline-generating defection, one of the markers of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and Western nations, bookends Ralph Fiennes’ remarkably fine movie, The White Crow, which opens in Canadian theatres on May 10.

Apart from directing the film, Fiennes stars in it as Alexander Pushkin, an instructor at the Kirov Ballet who discovered and nurtured Nureyev’s extraordinary talents. Fiennes recites his lines in Russian in this largely Russian-language movie, which unfolds in the Soviet Union and France between Nureyev’s birth on a train in 1938 and his defection at Le Bourget airport in Paris.

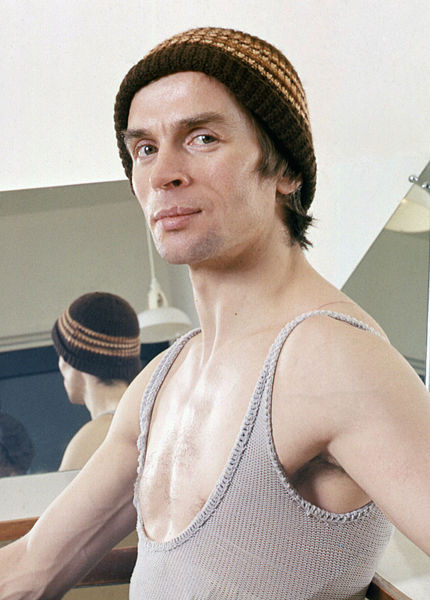

Fiennes focuses on Nureyev when he was a student at a leading ballet school in Leningrad in the mid-1950s. He makes only fleeting references to his hardscrabble boyhood in a Russian provincial town, and he ignores his ethnic and religious background as a Tatar Muslim. Nureyev, very ably portrayed by the Ukrainian dancer Oleg Ivenko, is seen as a rebel who marches to his own music. Dissatisfied with his teacher, he gets a new one in the person of Pushkin, a quiet, unobtrusive man who recognizes Nureyev’s qualities and works to shape them into something magical.

The White Crow, part of which was filmed at the Hermitage and Louvre museums, jumps from one decade to another. In the first scene, Pushkin, looking tired and dejected, is asked by a senior Soviet official to explain his pupil’s defection. The action shifts to a speeding train, where a woman strains to give birth to Nureyev. In the following segment, members of the Kirov Ballet arrive in Paris for an extended tour. It’s the first time in years that the famed company is touring France.

Neither shy nor reserved, Nureyev immediately stands out from his peers. Surprising his reticent and perhaps suppressed colleagues, he breaks social and ideological barriers by reaching out to a group of French officials from the Ministry of Culture who’ve arrived to greet the dancers at the airport.

Nureyev is in his element in Paris, breathing in its richness and opulence as he walks around the elegant city and admires exquisite paintings and sculptures at the Louvre. In Paris, too, he connects with Jean-Pierre (Raphael Personnaz), a French government official, and Clara Saint (Adele Exarchopoulos), a Chilean-French woman, both of whom will play a key role in his defection.

At first, Nureyev’s Soviet minder (Aleksey Morozov) is reluctant to allow him to set off on his own, fearing he may not return. But Nureyev is persistent, and the minder lets him go. He instructs two KGB agents to follow him. Later, he’s advised to avoid foreigners.

In 1950s Leningrad, Nureyev learns from Pushkin that ballet is more than just technique. As he refines his style, he’s invited by an older ballerina to be her dancing partner. After he breaks his foot in a rehearsal, Pushkin’s wife, Xenia (Chulpan Khamatova), invites Nureyev to live with them in their tiny apartment. An attractive middle-aged woman, she seduces the bisexual Nureyev. “It was bound to happen sooner or later,” she says.

As time passes, Soviet officials remind Nureyev that his appetite for the West borders on the subversive. He counters by saying he’s not interested in politics, but to no avail. Nureyev has become an object of suspicion in official Soviet circles, his brilliance notwithstanding.

The White Crow draws to a climactic close in Paris as Nureyev’s minder informs him he’s going back to Moscow rather than joining the Kirov Ballet on its next stop in London. Emotional scenes ensue as Nureyev is forced to reach a decision that will affect not only his career but his life.