The annual Toronto Jewish Film Festival , far and away the premiere cultural event in Toronto’s Jewish community, runs from April 30 to May 10. This year’s edition offers a great selection of 110 feature films, documentaries and shorts from 18 countries.

A preview:

Nazi Germany’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, understood the allure of film, calling it a powerful tool to harness public opinion.

Working on that assumption, Goebbels encouraged the captive German film industry to churn out movies for the masses. During the Third Reich, Germans had their pick of 1,200 freshly-minted feature films, some of which were purely propagandistic. After Germany’s defeat in World War II, the Allies banned 300 of the most pernicious ones. Today, 40 are still under lock and key.

Felix Moeller’s fascinating documentary, Forbidden Films, examines several of them and gives critics free rein to discuss the pros and cons of releasing them to the public without restrictions.

During the Nazi interregnum, German movies were extremely popular in Germany and throughout much of Europe. Movie goers flocked to theaters to watch an assortment of films, from thrillers to comedies. The exclusively propaganda films, which reversed reality, were anti-British, anti-Bolshevik and, of course, antisemitic. Toward the end of the war, with Germany reeling, their sole purpose was to lift sagging morale.

Germany’s invasion of Poland spawned Homecoming, which justified the aggression, portrayed Poles as blood-thirsty killers and glorified Polish ethnic Germans. In a nod to Berlin’s ethnic cleansing policy, a female character rejoices that neither Yiddish nor Polish will be spoken in Poland once the Nazis are victorious.

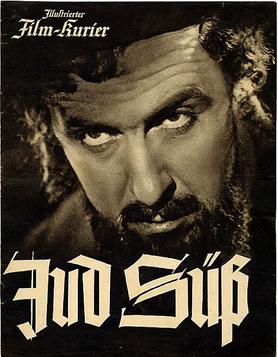

Under Goebbels’ watch, three vicious anti-Jewish films rolled off the assembly lines — Jew Suss, The Eternal Jew and The Rothschilds.

Loosely based on an 18th century incident, Jew Suss vilified Jews as exploiters and rapists of Aryan women. In one explosive scene, Jews are compared to locusts “devouring the land.” In The Eternal Jew, probably the crudest antisemitic film ever made, Jews are likened to scurrying, disease-ridden rats. The Rothschilds, which is slightly more sophisticated in tone, depicts the Frankfurt-based Jewish bankers as manipulators who profit from wars. “Blood always pays,” says a self-satisfied Rothschild.

In Hitler Youth Quex, a father — a Social Democrat — is dismayed to learn that his son has been converted to the Nazi cause. As the film ends, thousands of German youths sing in unison that they march for Adolf Hitler. Uncle Kruger, set in South Africa, is bitterly anti-British, while The Red Terror is viscerally anti-Soviet. Kolberg, an epic, appeared in 1945 to rally Germans as Russian tanks converged on Germany.

Forbidden Films takes us to a dark place and shines a light on it.

Belle and Sebastian takes place in Nazi-occupied France in 1943. The residents of St. Martin, an isolated village in the Alps, despise the Nazis. Some are involved in the smuggling of Jewish refugees to nearby neutral Switzerland.

Nicolas Vanier, the director, fleshes out this theme gradually as the cameras pan on the mountain scenery where St. Martin is located. The mountains are majestic and awe-inspiring, full of craggy peaks, passes, lakes and wild animals.

As this pastoral film opens, a man and a boy are on a mountain trek. Caesar (Tcheky Karyo), a shepherd, is looking for the wolves that have been devouring his sheep. Accompanying him is Sebastian (Felix Bossuet), his foster child. Caesar has told Sabastian that his mother is in America, beyond the mountains towering over St. Martin.

The German garrison in St. Martin demands the names of the French guides who’ve been smuggling “fugitives” into Switzerland. The Germans also demand free loaves of bread from the local bakery, which is run by Caesar’s niece, Angelina (Margaux Chatlier).

Sebastian is at the center of the film. As he wanders around the mountains, he befriends a wild and neglected dog. Belle, his new companion, mauls a German soldier, prompting the Germans to launch a hunt for her. Sebastian tries to save Belle.

The movie reaches an emotional high point as Ceasar, Angelina, Sebastian and Belle guide three Jews through the treacherous wintry landscape of the Alps, with a band of German soldiers in hot pursuit.

Belle and Sebastian is a feel-good film. Belle, of course, is the belle of the ball.

***

Bess Myerson made history in 1945, when she was crowned Miss America, the first and only Jewish woman ever to hold this coveted title. In David Lenik’s straightforward short, Bess Myerson: A Portrait of an Activist, she explains her ascendancy to fame and her connections to the Jewish world. Myerson was probably in her late 40s when she was interviewed.

Myerson’s sister, Sylvia, encouraged Bess to enter the Miss America contest. Sylvia figured that if her sister won, the family could use part of the $5,000 prize to purchase a piano. The Myersons were working-class people who could not afford such luxuries. Myerson’s parents, Louis and Bella, lived in the Sholem Aleichem apartment complex in the Bronx and brought up their children in an intensely Jewish and Yiddish milieu.

After winning the Miss America crown, Bess encountered “great antisemitism.” Unfortunately, she does not elaborate. Holocaust survivors told Myerson that her ascent to celebrity confirmed their hunch that they had made the right decision to settle in the United States. This, she says, was a source of gratification.

Myerson discusses the speeches she delivered in defence of tolerance and pluralism, the time she spent campaigning on behalf of Israel Bonds and her visits to Israel. When she met Golda Meir (nee Myerson), the Israeli prime minister quipped, “You’re the Myerson who made me famous.”

Bess Myerson is quite interesting, but it often feels like an Israel Bonds promotional film.

***

Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932), the chief executive officer of the Sears, Roebuck retail empire, was a great philanthropist. In his lifetime, he donated $62 million to charities. As a member of a historically persecuted minority, he identified with the plight of African Americans. Acting on his beliefs, he helped establish a network of schools for blacks in the South.

Aviva Kempner’s well-crafted film, The Rosenwald Schools, tells this story as it documents Rosenwald’s rise to fame as America’s most prominent retailer.

Rosenwald was a hard-nosed businessmen, but he was also a champion of civil rights in a country where African Americans were treated as second-class citizens. After reading Booker T. Washington’s memoir, Up From Slavery, he became acutely aware of the manifold problems African Americans faced in Jim Crow America.

Having contributed substantial funds to build YMCAs for blacks across the United States, Rosenwald agreed to invest in black schools. The African American education system was broken, being based on the outmoded separate but equal principle. Spurred on by Washington, Rosenwald committed himself to improving the standard of education in the African American community.

***

The late Nathan Handwerker was an American success story, the founder of the Coney Island hot dog stand which blossomed into an empire/institution. Famous Nathan, directed by his grandson Lloyd Handwerker, is an even-handed portrait of a driven man who devoted himself, body and soul, to his booming food business.

In the only taped interview he ever made, Handwerker talks about his life. He was born in Poland in 1892, the son of an impoverished shoemaker who sired seven boys and six girls. For a while, Handwerker toiled as a baker in Radom. A natural entrepreneur, he immigrated to the United States via Belgium. He opened his frankfurter stand in 1916 and never looked back, riding out the Depression by selling five cent hot dogs.

Former employees — waiters, countermen and managers — and family members paint a mixed picture of Handwerker as a tyrant and a saint. A dour person, he was a perfectionist and workaholic who was parsimonious with his praise. Tough and critical, he was feared by his workers. Yet he was an equal opportunity employer, hiring African Americans and giving valued employees interest-free mortgage loans.

While he provided relatives with jobs, he could be mean and unreasonable. He loved his children, but did not shower them with displays of affection. He encouraged them to join the family business, but drove Sol, one of his sons, out of it. He and his wife were supposedly happily married, but according to some, they constantly bickered.

Famous Nathan delivers a nuanced portrait of the one and only Nathan Handwerker.