Olivier Lubrich, a professor of German and comparative literature at the University of Berne in Switzerland, has compiled a historically useful anthology of essays and letters, both published and unpublished, describing life in Nazi Germany. Travels in the Reich, 1933-1945 (The University of Chicago Press) presents a chilling portrait of a nation under the thrall of a barbaric ideology and regime.

In a letter from Berlin dated April 8, 1933, Swiss letter writer Annemarie Schwarzenbach says that Germany’s antisemitic policies are having “catastrophic results” on “the whole German economy.”

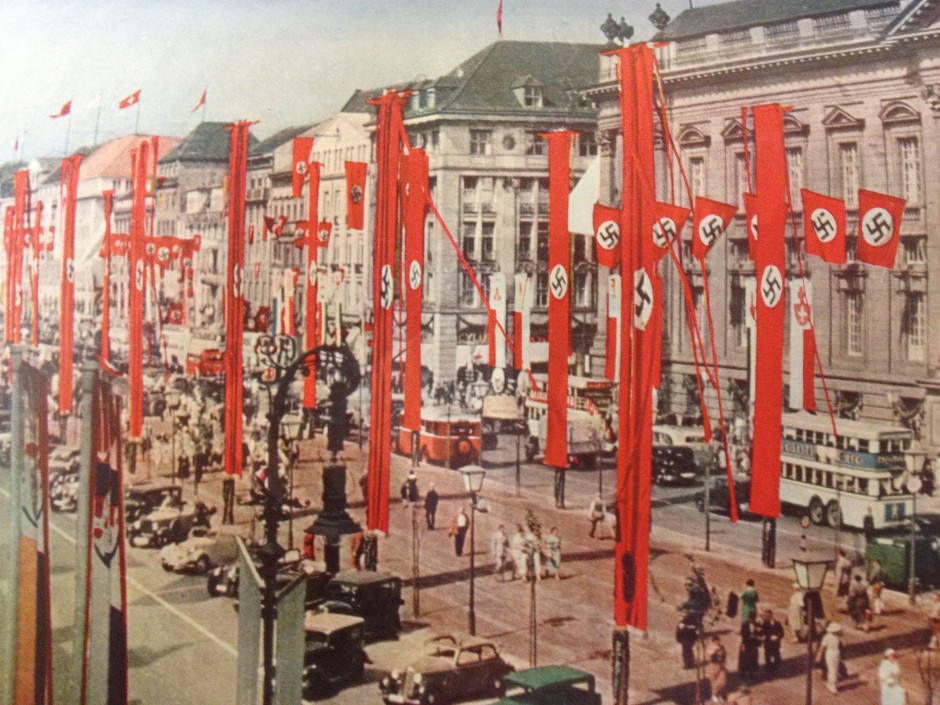

Driving through a town garlanded with antisemitic posters, Martha Dodd, the daughter of the U.S. ambassador to Germany, confesses that “the Nazi spirit of intolerance” in its “complete significance” has only begun to dawn on her.

Konrad Warner, a Swiss reporter based in Germany, finds himself in the thick of a crowd in 1935 welcoming Adolf Hitler. The people are mesmerized by his presence. “There is no doubt that he achieved a great effect,” he writes.

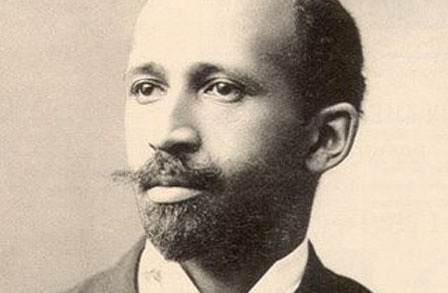

W.E.B. DuBois, the African American scholar and civil rights activist, went to Germany in 1936 for a five-month research trip. He observes: “Germany is silent, nervous, suppressed. It speaks in whispers. There is no public opinion, no opposition, no discussion of anything.” He likens the prejudice against Jews to “an attack on civilization, comparable only to such horrors as the Spanish Inquisition and the African slave trade.” The minister of education tells DuBois that Jews to a “foreign element.”

Rene Juvet, a Swiss merchant, is in Bayreuth when Kristallnacht breaks out in November 1938. “I passed several Jewish shops, all of which had their windows shattered,” he says. He reports that in the venerable city of Wurzburg, the rector of the university “led the pogrom in person.”

Meinrad Inglin, a Swiss writer travelling through the country in the winter of 1940, is hopeful that the Nazi regime will be replaced by a better Germany. As he puts it in a prescient comment, “This more humane Germany (will) embrace the European cultural community to which it belongs.”

Harry Flannery, an American correspondent, passes through Frankfurt in 1941 and is surprised by the number of Jews still left in Germany. “It was hard to believe that thousands could remain despite the fact that they were denied every means of life.”

He adds, “No store could sell to Jews except within a few certain hours a day, and some stores refused to sell to Jews altogether. The Jews had only the fundamental ration cards, each marked with the word Jude, and were denied fruits, most vegetables, cigarettes, chocolates, and all other special allotments, even for children.”

Joseph Goebbels, the propaganda minister, blamed Jews for the war, he says. “They are suffering no injustice in the treatment we give them,” claimed Goebbels. “They more than earned it.”

Toward the end of the war, Gosta Block, a German who had lived in Sweden, says that conditions for Jews are “completely hellish.” He elaborates, “Jews in today’s Germany are truly hunted animals. They lack all the rights of citizens, and they are reminded every day that (they) are the enemy of the German people.”

During a trip through Germany in 1944, the Swiss journalist Rene Schindler comes across ghostly cities: “The same picture everywhere. In Munch, Augsburg, Stuttgart, Darmstadt, Frankfurt, Leipzig and Berlin. Ruins and rubble everywhere, debris and broken glass.”

Wiking Jerk, a Scandinavian visitor, claims that Goebbels was strung up on a gallows in Berlin after committing suicide. “A male corpse was hanging. I went closer. It looked like Goebbels! Although the (Russians) had crushed his nose and given the corpse a deep bayonet stab in the throat, it was impossible to be mistaken … Red Army soldiers stopped in groups, pointed at the hanging body, and laughed.”

These impressions add texture to the body of literature on Nazi Germany.