As newly-inaugurated U.S. President Donald Trump settles into his job at the White House, a host of thorny foreign policy issues are competing for his attention.

How will he manage bilateral relations with China and Russia? How strong a position will he stake out in confronting the Islamic State organization? What will be his attitude to Israeli settlements in the West Bank and the Palestinians’ quest for statehood?

And last but not least, how will he deal with the nuclear agreement Iran signed with the six major powers, including the United States, in 2015?

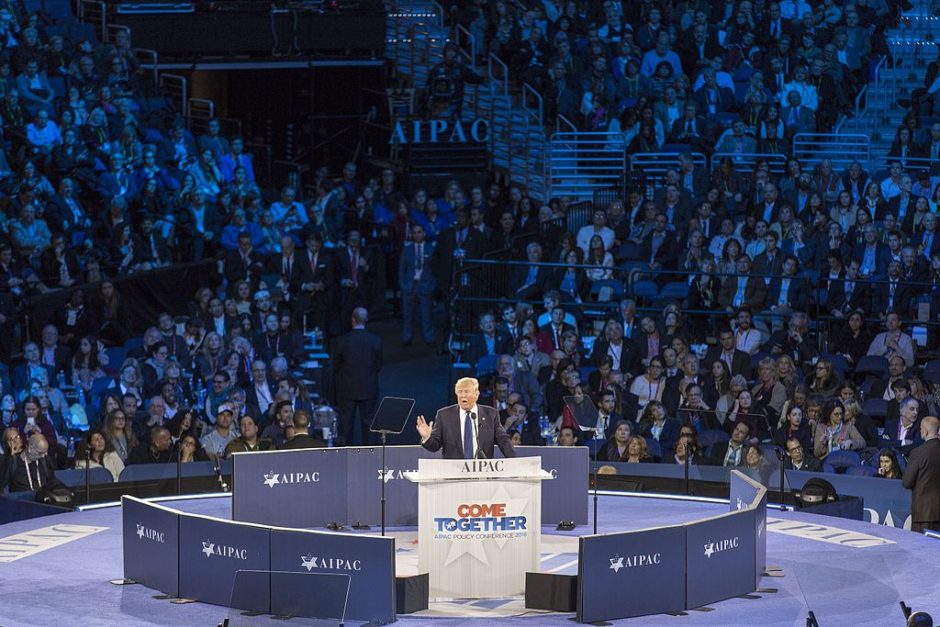

Since his inauguration on January 20, Trump has publicly addressed these issues in various degrees, but kept his comments on Iran to a bare minimum. During his presidential campaign, however, Trump regularly blasted the nuclear accord (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action), which freezes Iran’s nuclear program and provides Iran with relief from crippling economic sanctions to the tune of about $100 billion.

Calling the agreement “disastrous” and one of the worst deals in history, Trump pledged to review or “dismantle” it, much to the satisfaction of one of its most vociferous critics, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel, who described it as a historic mistake and denounced it in a speech to the U.S. Congress last March.

Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, fought hard to implement it, but realizing it might not pass muster in a Republican Party-dominated Congress, he chose to ratify it by means of a unilateral executive order.

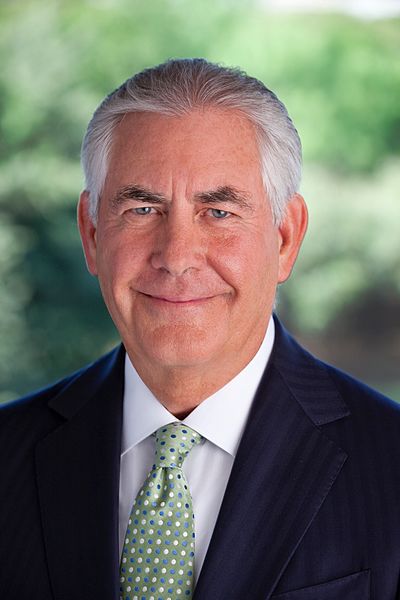

With the stroke of a pen, Trump can push back by the clock by rescinding Obama’s order. So the question at this point is whether Trump will honor his promise and tear up the agreement, which has been approved by the United Nations Security Council. But he may think twice before scuttling it because U.S. allies like Britain and France firmly support it and because two of his most senior cabinet members, Defence Secretary James Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, have urged caution.

During his confirmation hearing before the U.S. Senate earlier this month, Mattis — a retired four-star general who commanded U.S. forces in Iraq — said the United States has an obligation to adhere to it. “I think it is an imperfect arms control agreement — it’s not a friendship treaty,” he said. “But when America gives its word, we have to live up to it and work with our allies.”

Tillerson, the former chief executive officer of the Exxon oil company, proposed a “full review” of it and stronger compliance from Iran, but stopped short of calling for its outright dismantlement.

Eliot Engel, one of the relatively few Democrats in the House of Representatives who opposed it, is also circumspect, having warned that the United States has more to lose by disengaging from it.

In its waning days in office, the Obama administration hailed it as one of its major foreign policy achievements. The White House, in a press release this month, said it had “achieved significant concrete results,” subjecting Iran to an intensive inspection and verification regimen and forcing Iran to dismantle two-thirds if its centrifuges and reduce its stockpile of uranium by 98 percent.

John Kerry, the outgoing secretary of state, said it was working and that all the signatories — the United States, Iran, Russia, China, Britain, France, and Germany — have honoured their commitments.

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency, Iran has dismantled much of its nuclear program, thereby fulfilling its end of the bargain.

Iran’s president, Hassan Rouhani, certainly has no intention of returning to the negotiating table. At a news conference in Tehran two weeks ago, he declared, “The nuclear deal is finished. It has become an international document. It is a multilateral accord and there is no sense in renegotiating it.”

Although Iranian hardliners would disagree with him, Rouhani is of the view that it has been beneficial to Iran. “We can now export as much oil as possible,” he said. “International transportation and shipping are much less inexpensive.” And in a reference to Western countries that have dropped their sanctions against Iran, Rouhani added, “Many trade and foreign investment contracts and agreements have been signed.”

Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif, Iran’s chief negotiator at the nuclear talks, does not believe it’s in jeopardy. But if the situation changes for there worse, he added, “we have options for every alternative.”

Should Iran come under military attack, Iranian Defence Minister Hossein Dehghan warned last month, the Iranian armed forces would respond aggressively, resulting in the destruction of “the Zionist regime” and the Arab Gulf states.

Dehghan may have been reacting to a comment made by Netanyahu in early December. Addressing the annual Saban Forum in Washington, D.C. via a satellite feed, Netanyahu said Israel is fully committed to preventing Iran from acquiring a nuclear arsenal and would seriously consider using military force in pursuit of this objective.

Netanyahu is concerned that the nuclear agreement, which is due to lapse in 10 to 15 years, will pave the way for Tehran’s eventual acquisition of atomic weapons. Israel seeks the removal of Iran’s nuclear program, but Netanyahu may settle for a full enforcement of the agreement, a course of action advocated by Joseph Lieberman, a former U.S. senator, close friend of Israel and currently chairman of United Against Nuclear Iran.

In an op-ed piece in The Washington Post recently, Lieberman and his co-author, Mark Wallace, a former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, wrote that the Trump administration should first try to enforce it and then renegotiate it “beyond the confines of the nuclear issue.”

They claim that Iran has twice exceeded its allotted limit for heavy water and test-fired multiple ballistic missiles. Lieberman and Wallace also contend that Iran must “verifiably curb its regional aggression, state sponsorship of terrorism and domestic repression of human rights.” In return for acceding to these demands, they note, Iran could be given “broad-based sanctions relief and even normalization of relations” with the United States and other Western nations.

If the Iranian government does not comply, they argue, Trump should impose a new round of comprehensive secondary sanctions against Iran and, if necessary, repudiate the nuclear agreement altogether. “Such a step-by-step strategy would make clear that the United States is willing to work with Iran but that there will be consequences for the Iranians if no diplomatic solution is reached,” Lieberman and Wallace wrote.

Trump has yet to decide which path he will embark upon with respect to the agreement. But on January 29, in a telephone conversation with King Salman of Saudi Arabia, he said he would “vigorously enforce” it.

Which means, of course, that he has come to terms with the agreement and will not try to scrap it.