Turkey, in a remarkable volte-face, is trying to rehabilitate its battered bilateral relations with Israel.

Only nine months ago, during the fourth cross-border war in and around the Gaza Strip, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan vigorously blasted Israel. An Islamist and a vocal champion of the Palestinian cause, he condemned Israel as a “terrorist state” and resorted to antisemitic imagery to brand Israelis as “murderers” of children and old people who are “only satisfied by sucking their blood.”

Erdogan’s inflammatory language brought Turkey’s often mercurial ties with Israel to a nadir and seemed to rule out the possibility of an improvement in Israel’s troubled relations with Turkey as long as he remained in office.

This may have been a hasty reading of an evolving situation. In the past few months,Turkey has reached out to Israel in an attempt to paper over their differences and find common ground. In a tangible expression of his desire for reconciliation, Erdogan has invited Israeli President Isaac Herzog for a visit to Turkey from March 9-10, and Herzog has accepted the invitation.

The director-general of Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Alon Ushpiz, flew to Turkey earlier this month to arrange it. Ushpiz’s trip to Turkey was itself significant, having been the first by a senior Israeli official in almost six years.

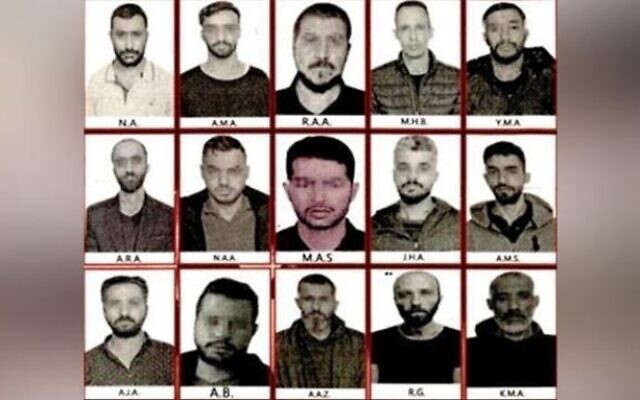

Strangely enough, it came on the heels of news that 16 men, including Syrians and Palestinians, had gone on trial in Istanbul on charges of spying for Israel. The Israeli government denied the defendants were Israeli spies.

In spite of this jarring development, a Turkish delegation visited Israel on February 17 to finalize the details of Herzog’s impending visit. It was headed by Ibrahim Kalin, Erdogan’s senior advisor, and Sadat Onal, Turkey’s deputy foreign minister.

Prior to their arrival in Jerusalem, Erdogan issued a statement saying that Herzog’s forthcoming visit would be mutually beneficial. “God willing, it will be good for Turkey-Israel relations for such a step to be taken after such a long period.”

What he meant was clear to anyone who has followed the rollercoaster nature of Israel’s relationship with Turkey.

Although Turkey — the successor state of the Ottoman Empire — was the first Muslim nation to recognize Israel, Turkish governments kept relations with Israel on a fairly low level for decades. All this changed with the advent of the 1993 Oslo peace process, which launched direct peace talks between Israel and the PLO.

During this honeymoon period, when the protracted Palestinian issue appeared ripe for resolution, Israel and Turkey formed unprecedented strategic political and military bonds. It was a time when Erdogan paid his only visit to Israel, when Turkey played a role as a mediator between Israel and Syria, and when Shimon Peres, the then Israeli president, delivered a speech in the Turkish parliament.

This golden era came crashing down during the first Gaza war, which raged from the end of 2008 until the first month of 2009. Erdogan harshly denounced Israel’s offensive, but his denunciation was merely a foretaste of things to come.

In May of 2010, Israeli naval commandos intercepted the Mavi Marmara, a Turkish vessel which led a flotilla of ships attempting to break Israel’s blockade of Gaza, which has been ruled by Hamas since its election victory in 2006. Nine Turks, plus an American citizen of Turkish descent, were killed during the violent altercation.

Lashing out at Israel, Erdogan significantly downgraded Turkey’s relations with Israel, and a deep chill set in. In 2013, U.S. President Barack Obama convinced Benjamin Netanyahu, the then Israeli prime minister, to phone Erdogan and issue an apology. Israeli and Turkish diplomats spent the next three years sorting out the mess.

Israel and Turkey exchanged ambassadors and resumed normal relations in 2016. But only two years later, Turkey expelled the Israeli ambassador in Ankara, Eitan Na’eh. Israel retaliated by expelling his Turkish counterpart in Tel Aviv. Turkey took this drastic decision after the United States transferred its embassy to Jerusalem and after deadly clashes broke out between Israeli soldiers and Palestinian protesters along the Gaza border.

As a result of these events, Israeli travellers cancelled vacation trips to Turkey, dealing a heavy blow to Turkey’s vital tourist industry. Israeli-Turkish trade, however boomed, being impervious to the fluctuations in Israel’s strained political relations with Turkey.

Erdogan, nevertheless, decided it was in Turkey’s best interests to forge a rapprochement with Israel. His motives were clear. In recent years, Erdogan’s abrasive policies have ruffled feathers abroad, having alienated nations such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Greece and the United States. This has left Turkey somewhat internationally isolated and its policy of “zero problems” with its neighbors in shambles.

Turkey, too, watched with concern as Israel, Greece and Cyprus negotiated a landmark agreement to build a 1,900-kilometer gas pipeline from the Mediterranean Sea to markets in Europe.

In addition, Turkey’s plan of replacing the United States with Russia as its chief ally has not panned out because Erdogan and Russian President Vladimir Putin find themselves on opposite sides of conflicts in Syria, Libya, Azerbaijan and Ukraine.

Given these factors, plus the dire state of Turkey’s inflation-ridden economy, Erdogan concluded he had nothing to lose by reconciling with Israel, whose influence in the United States can be helpful to Turkey. In what can only be described as a charm offensive, Erdogan began to seriously court Israel.

Last November, he agreed to release Mordi and Natali Oknin, two Israeli tourists who were arrested as spies after taking pictures of the presidential palace in Istanbul. Erdogan personally intervened in the case, facilitating their release and prompting Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and Isaac Herzog to thank Erdogan for his efforts.

During their respective conversations, Erdogan stressed the importance of Turkey’s relations with Israel, calling them a cornerstone of peace, stability and security in the Middle East. He also expressed a desire for a comprehensive dialogue with Israel on bilateral and regional issues.

In December, Erdogan told journalists he was receptive to improved ties with Israel, but he urged Israel to adopt “more sensitive” policies toward the Palestinians.

On December 23, Erdogan met a group of Jewish leaders in Ankara. After denouncing antisemitism and Islamophobia as a “crime against humanity,” he said that a sincere attempt by Israel to advance peace with the Palestinians “will undoubtedly contribute” to Turkey’s normalization of relations” with Israel.

Last month, Erdogan called Herzog to offer his condolences on the death of his mother. It was his second call to Herzog. In July, he phoned Herzog after his inauguration as president.

On January 20, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu phoned Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid to inquire about his health following his recovery from Covid-19. It was the first conversation between Israeli and Turkish foreign ministers in nearly ten years.

On February 4, Erdogan said he hoped Turkey and Israel could cooperate in the delivery of Israeli natural gas from the Middle East to Europe. “We could use Israeli natural gas in our country, and beyond that, we could also work together to carry it to Europe,” he said.

It goes without saying that Israel is interested in improving its relations with Turkey, a regional power and the sole Muslim member of the NATO alliance. But from Israel’s point of view, there are two major problems that must be resolved before this can happen.

Firstly, Israel expects Erdogan to shut down Hamas’ office in Turkey. According to Israel’s Shin Bet Intelligence agency, Hamas operatives have planned numerous terrorist attacks against Israel from their base in Istanbul.

Secondly, the Israeli government takes a dim view of Turkey’s activities in East Jerusalem, suspecting that Turkish cultural institutions there engage in hostile acts against Israel.

From Turkey’s perspective, Israel’s alliance with Greece and Cyprus is troubling. Israel has no intention of downgrading its ties with Greece and Cyprus to please Turkey. Indeed, Herzog intends to visit Greece on February 24 and Cyprus on March 2.

At the end of the day, the Palestinian problem will determine whether Turkey can fully normalize its relations with Israel. As Cavusoglu said on February 9, “Any step we take with Israel regarding our relations, any normalization, will not be at the expense of the Palestinian cause.”

Turkey supports a two-state solution, but the current Israeli government rejects it.

Erdogan elucidated Turkey’s position in a speech at the United Nations last September. Castigating Israel’s “oppression” of the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, he emphasized “the necessity of reviving the peace process” so that Palestinian statehood can be achieved “as soon as possible without further delay.”

Although Turkey and Israel are at odds over the Palestinian issue, their interests are aligned in Azerbaijan, a Muslim country near Iran. During its successful war with Armenia in 2020, Azerbaijan deployed both Israeli and Turkish weapons. Israel regards Azerbajan as an ally in its conflict with Iran, while Turkey relates to Azerbaijan as a brotherly nation.