An American university professor who declined to write a letter of recommendation for a Jewish student intending to study in Israel for a semester acted in a discriminatory manner at odds with the hallowed principles of academic freedom.

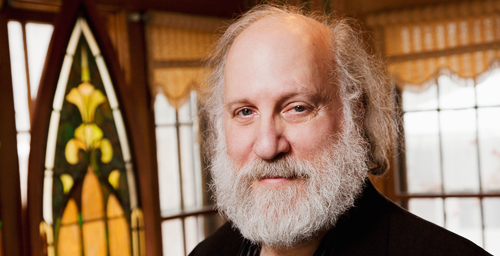

John Cheney-Lippold, who teaches American culture and digital studies at the University of Michigan, told Abigail Ingber that his support for the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, which exclusively targets Israel, precludes him from fulfilling her request.

“As you may know, many university departments have pledged an academic boycott against Israel in support of Palestinians living in Palestine,” he wrote Ingber in an email. “This boycott includes writing letters of recommendation for students planning to study there.”

Reacting to the backlash which erupted following his inappropriate decision, Cheney-Lippold expressed defiance.

“I do not regret declining to write the letter, precisely because I am boycotting injustice,” he wrote. “I would hope anyone who cares about injustice, such as Israel’s unequal treatment of Palestinians, would make a similar decision… Israeli universities are complicit institutions — they develop weapons systems and military training. Standing up for freedom, justice and equality for all is something I’m proud of.”

He categorically rejected the idea that his refusal was tantamount to antisemitism, as some allege, saying he was boycotting Israeli universities rather than Ingber. Cheney-Lippold added he would be willing to write Ingber a letter of recommendation to any university outside Israel.

This case raises complex questions, particularly in light of the fact that the University of Michigan and the American Association of University Professors oppose boycotts, though the American Studies Association supports them.

The questions are: Does a professor have the right to impose his or her political views on a student? In doing so, is a professor impinging on a student’s academic freedom?

The answer to both is a resounding no.

Like all professors, Cheney-Lippold is ethically obliged to provide letters of recommendation to students with acceptable grades. Since Ingber’s class marks did not come up in his letter of rejection, one can only assume that her academic performance was satisfactory and that she qualifies for a semester abroad.

As the University of Michigan suggested in a statement, Cheney-Lippold contravened his informal academic contract with Ingber due to the egregious position he adopted. “Injecting personal politics into a decision regarding support for our students is counter to our values and expectations as an institution,” the university correctly pointed out. An earlier statement issued by the university described Cheney-Lippold’s decision as “disappointing.”

This case has elicited measured comments from the American Association of University Professors.

Hans-Joerg Tiede, the associate secretary of its Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure and Governance, said, “I think that it’s generally understood that writing such letters falls within the professional duties of faculty members. I also think that it’s generally understood that faculty members may decline to write a particular letter in particular instances, for example, because they believe that they have insufficient information on which to base such a letter. In general, refusing to write a letter of reference on grounds that are discriminatory would appear to be at odds with the AAUP’s Statement on Professional Ethics.”

John K. Wilson, the co-editor of the AAUP’s blog, Academe, said, “Writing a letter of recommendation is not like teaching a class. It is a voluntary activity, and not a necessary part of one’s academic work. Professors are given broad discretion to decide how, and if, to write a letter. And they can decline if they think the opportunity is not in the best interests of the student, even if the student disagrees. However, I think it is morally wrong for professors to impose their political views on student letters of recommendation.”

Cary Nelson, a former AAUP president, said that professors like Cheney-Lippold open themselves to punishment. “What the professor did violated the student’s academic freedom — the right to apply to study at any program anywhere in the world,” said Nelson, a professor emeritus of English and Jewish culture and society at the University of Illinois.

According to Nelson, a professor is in violation of professional ethics when he or she declines to write a letter for a student purely on the basis of politics. A faculty member cannot decline to write a letter of recommendation, he said, if that member’s reason hinges on political objections to the university or to the country in which the student is interested in studying. Nor can a professor decide whether a student’s politics is legitimate or illegitimate, he argued.

Henry Srebrnik, a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island, wrote in response to a query: “I think the professor has the right not to write a letter but in this case, since it’s not about the student’s record, but rather the university she wants to attend, I’d say the student would have the right to grieve.”

In retrospect, Cheney-Lippold infringed on Ingber’s intrinsic rights as a student when he declined to write her a letter of recommendation to study in Israel. The University of Michigan, being opposed to academic boycotts, should deal with this test case on the basis of its anti-boycott policy.