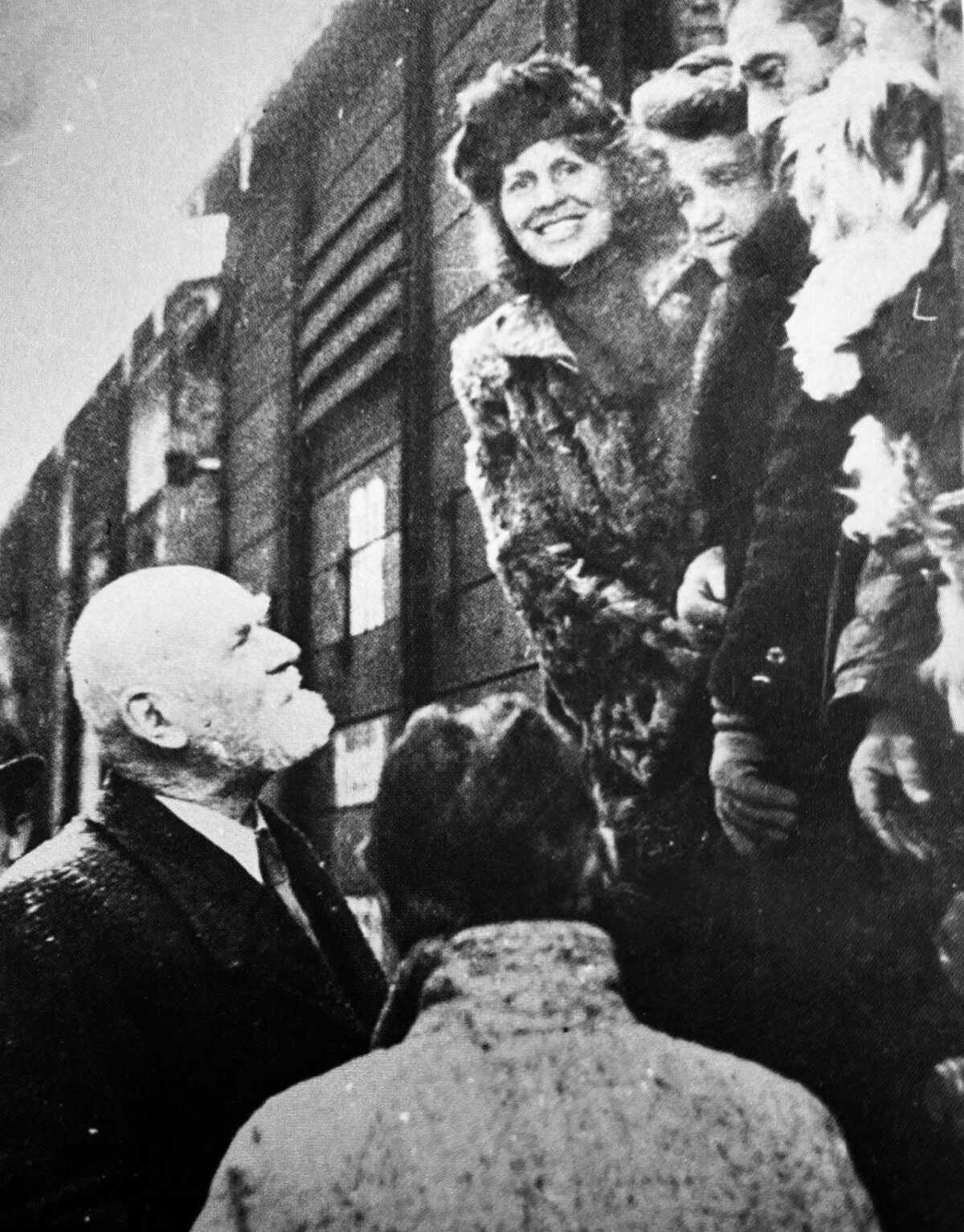

In the winter of 1947, Theodor Korner, the socialist mayor of Vienna, went to the city’s central train station to greet 760 Viennese Jews returning from exile abroad. Like tens of thousands of other Jews, they had been driven out after the Anschluss, Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938.

On the eve of World War II, 206,000 Jews lived in Austria, almost all of them in Vienna. Two-thirds emigrated after the Anschluss, which relegated Jews to second-class citizenship and exposed them to harsh forms of persecution.

Austrian Jews found havens in, among other countries, Britain and the United States. Fourteen thousand settled in Mandate Palestine.

The vast majority of Jews who remained behind were eventually deported and murdered in Nazi extermination camps and ghettos. This was the abysmal fate that befell some 65,000 Jews.

Several thousand Jews, some of partial Christian ancestry or in privileged mixed marriages, survived the Nazi genocidal onslaught. Upwards of 800 managed to survive in hiding as so-called “U-boats.”

With Germany’s defeat in the war, Austria regained its independence. While most Viennese Jews living abroad chose to remain in their new homes, a relatively small number began to return to Vienna to restart their lives. By the spring of 1947, about 2,000 had returned. Joining them there were 35,000 displaced Jewish refugees from European countries.

In The Compromise of Return: Viennese Jews After The Holocaust (Wayne State University Press), a thorough and lucid work of scholarship, the American historian Elizabeth Anthony focuses on the immediate postwar period during which Austrian Jews went back to the city they loved.

“Jewish returnees were Viennese, not just in thought and identification from afar, but in the action of their return as well,” writes Anthony, the director of Visiting Scholar Programs at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. “These returnees still conceptualized Vienna as home and wanted to go back and reengage.”

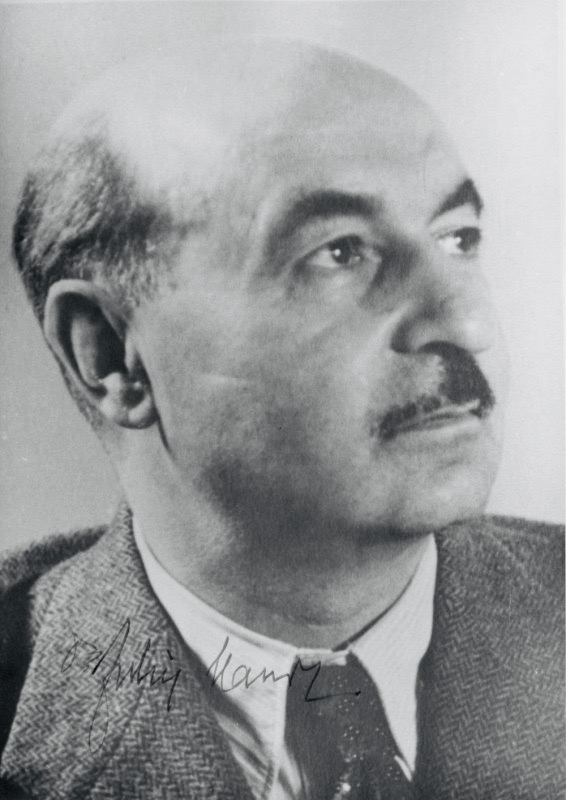

The first Viennese Jews to “return” reemerged from hiding places. The second and third groups consisted of concentration camp survivors and politically committed social democrats and communists who would help rebuild Austria. One such person was Bruno Kreisky, a Social Democrat who would be elected Austrian chancellor in 1970.

The fourth group was comprised of professionals like doctors, lawyers and writers, whose training and certification were entirely Austrian. In this respect, Anthony cites the cases of Friedrich Torberg and Felix Mandl.

Torberg, a journalist whose books were banned by the Nazis, moved back to Vienna in 1951 and was subsequently hired as the theater critic of a major Viennese daily.

Mandl, a physician who practised at the Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem, returned to Austria and was appointed the director of surgery at the Emperor Franz Josef Hospital in Vienna.

They were the sons and daughters of Jews who had dwelled in Austria for centuries and whose ancestors had been emancipated by the Habsburg Empire in 1867. “Jews considered themselves to be politically Austrian, culturally German and ethnically Jewish,” says Anthony.

Despite their integration into Austrian society, they faced antisemitism of the kind espoused by Karl Lueger, Vienna’s mayor from 1897 to 1910, and his disciples. With the exception of the Social Democratic Party, antisemitism remained pervasive in Viennese politics.

During the 1930s, Austria was in turmoil as its chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss, outlawed the Nazi, Communist and Social Democratic parties. His successor, Karl von Schuschnigg, was assassinated by Nazi thugs.

With Austria’s annexation in March 1938, Germany installed Arthur Seyss-Inquart, a Nazi, as its leader. German troops poured into the country in the same month, sealing Austria’s fate. Austrian Catholics generally welcomed the Anschluss, which had a devastating impact on the Jewish population.

From that point forward, Jews were subjected to violence, plunder and persecution on a massive scale. Within days of the Anschluss, SS lieutenant Adolf Eichmann arrived in Vienna to coordinate the antisemitic campaign against Jews.

“Many Austrian gentiles stood to benefit greatly from the subjugation and exploitation of their Jewish neighbors,” says Anthony.

Pogroms erupted in Austria in October 1938, a month before Kristallnacht in Germany.

During the war, Allied aircraft carried out 53 air raids over Vienna, killing 8,769 civilians, damaging nearly one-third of its buildings, and leaving the once-grand capital of the Habsburg Empire virtually in ruins.

“The city lacked infrastructure, resources, a skilled labor force, and energy sources,” says Anthony of post-war Vienna, adding that its residents subsisted on a near-starvation diet.

The final days of the war were among the most dangerous and terrifying for Jews in Vienna. They brought chaos, uncertainty, increased antisemitic hostility, and fierce fighting between the Red Army and its foes, the Wehrmacht and the SS.

When it was finally liberated, Vienna was home to 5,799 Jews, of whom 1,053 practised Judaism.

Before and during the first weeks of peace, some Jews found new apartments quite easily, Many had been owned by Nazis fleeing the advancing Soviet army, which occupied Austria along with U.S., British and French troops.

Two years prior to Germany’s capitulation, the Allies issued the Moscow Declaration, which annulled the Anschluss, called for a sovereign Austria, and described Austria as “the first free country to fall a victim to Hitlerite aggression.”

Post-war Austrian politicians enthusiastically embraced the “first victim” paradigm and worked diligently to sidestep culpability for Nazi war crimes by placing total blame on Germany.

“They ultimately took advantage of evolving Cold War politics to pit Western powers against the Soviets for financial gain and to secure all four Allies’ acceptance of the narrative of Austria as the Nazis’ first victim,” says Anthony. “With this logic, Austria as a country and all Austrians as individuals were victims.”

Using the argument that Austria had ceased to exist as a state between 1938 and 1945, Austrian politicians such as Karl Renner, the first postwar Austrian chancellor, tried to avoid providing aid to surviving Jews, particularly those living abroad. “His concern about the nation’s pain, suffering and damages never included the loss of nearly 200,000 Austrian Jews to forced emigration and murder,” she goes on to say.

In the main, Jewish survivors in Austria had to turn to internal and external Jewish community organizations for assistance.

According to Anthony, few Christian Austrians showed sympathy or appreciation for the ordeal Austrian Jews had endured from 1938 onward. Some even displayed outright hostility, and Jewish returnees became the targets of “new and renewed” antisemitism in Vienna. Several politicians even criticized Jews who had sought safety and comfort abroad after the Anschluss!

At the same time, postwar political parties tried to recruit former Nazis in the name of national reconciliation and unity. In 1946, 90 percent of former Nazi Party members were amnestied, reinstated to their jobs, and paid compensation for material and financial losses after 1945.

“Parties vied for the electoral support of former Nazis and determined that doing so required an official silence about the past …” Anthony notes.

Property restitution was another burdensome issue. Sixty thousand Jewish-owned apartments had been Aryanized by the Nazis, but when their rightful proprietors attempted to reclaim them, they often ran into a brick wall. Scarcely any claims were recognized by the government, and many returnees simply gave up on their quest to retrieve lost properties.

In fact, the Austrian government passed restitution legislation, but it was riddled with loopholes that frustrated Jewish claimants.

Jews who returned Austria learned that silence about the Nazi past was essential in the post-war era. “Silence allowed survivors to live among former Nazis and to suppress thoughts about their possible involvement in war crimes,” says Anthony of the unpalatable compromise Jews were compelled to make.

Their acceptance of hard, cold reality enabled Jewish returnees to cohabitate with their former tormentors in a reborn Austria.