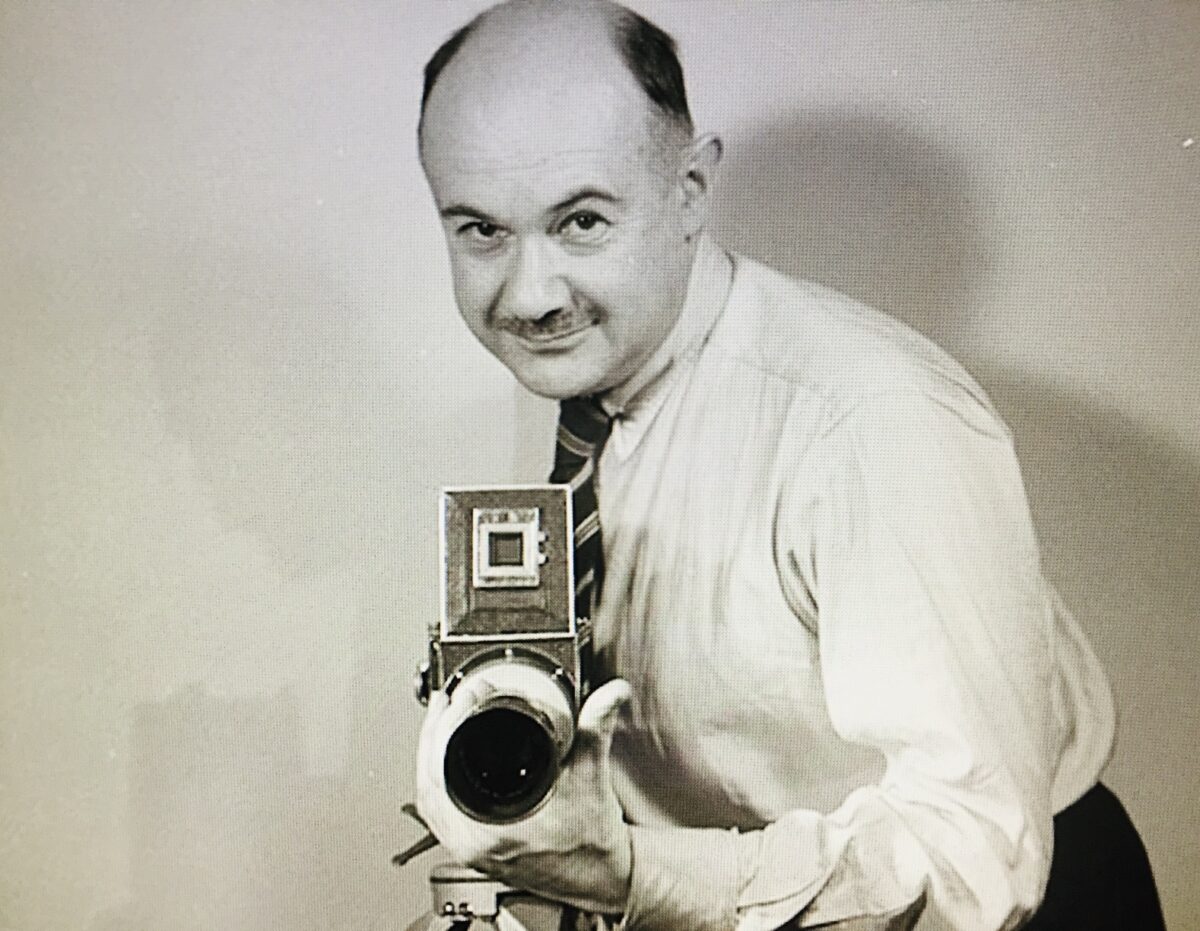

Thanks, in part, to Roman Vishniac (1897-1990), a towering figure in modern photography, the Jewish communities obliterated by the Nazi hordes during the Holocaust will always be remembered.

Vishniac, a Russian Jew, travelled to Eastern Europe and the Balkans from the mid-1930s onward to photograph Jews from all walks of life in Poland, Lithuania, Czechoslovakia and Romania. His photographs are important because they are captivating time capsules of a murdered people.

During the post-war period, he wrote two books containing his stark and affecting black-and-white photographs: Polish Jews: A Pictorial Record (1947) and A Vanished World (1983), both of which earned him praise and admiration.

After his death, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. created a permanent exhibition of his photographs.

Laura Bialis’ fascinating documentary, Vishniac, explores his life and career. A seamless amalgam of file footage, reenactments and interviews with Vishniac’s descendants and experts on photography, it will be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival on June 11.

Vishniac’s daughter, Mara, appears throughout it. As a girl, she watched him develop his photographs in a darkroom. Following his passing, she curated and donated the body of his work to various institutions in the United States.

Vishniac was born into a prosperous family in czarist Russia and grew up under privileged circumstances. Particularly interested in science, he studied biology. With the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the Vishniacs moved to Berlin, a center of photography in Europe.

Although his father set him up in a range of businesses, he devoted himself instead to honing his skills as a photographer. During the Weimar era, he specialized in cityscapes. With the rise of Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist Party, he focused on Nazi propaganda posters in the German capital.

He and his Latvian Jewish wife had a rocky relationship because Vishniac was a workaholic and unfaithful. He would eventually marry the woman with whom he had an affair in Germany.

In 1935, the American Joint Distribution Committee hired him to document Jewish life in Eastern Europe. Its objective was to raise funds for destitute Jews there. An assimilated Jew, Vishniac discovered a world of Jewishness and deep spirituality there.

Wielding a Leica camera, he travelled from cities to villages, photographing adults and children, husbands and wives, families, manual workers, farmers, professionals, yeshiva students and rabbis. According to Mara, he felt close to his subjects.

Despite the upsurge of state-sponsored antisemitism in Germany, Vishniac remained there. In the wake of Kristallnacht, in November 1938, Mara and her mother went to Sweden. Vishniac’s son, Wolf, was sent to the United States. Vishniac temporarily settled in France. Bialis does not explain why the Vishniacs did not leave Germany much sooner.

Reunited in Lisbon in 1940, they found a refuge in the United States. Shortly after their arrival in New York City, he and his wife divorced. As the war in Europe dragged on and the Holocaust unfolded, Vishniac eked out a living as a portrait photographer. After hostilities ended, he exhibited his pre-war photographs. Bialis leaves a viewer in the dark regarding the reception they received.

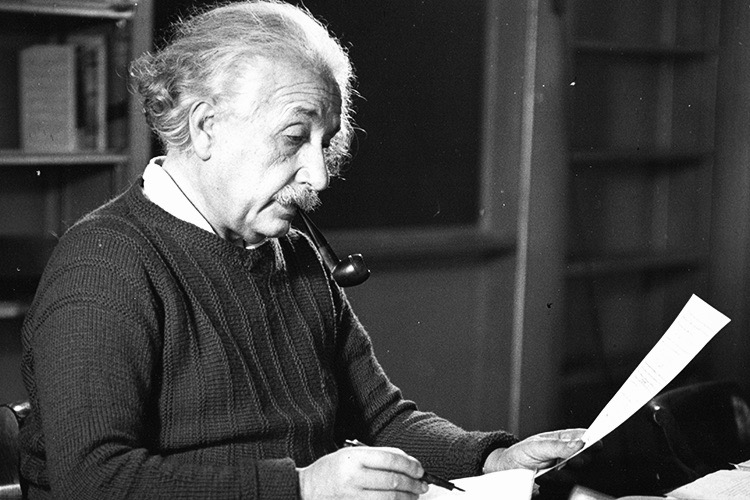

Vishniac took some of the most striking and iconic photographs of the physicist Albert Einstein, who was based at Princeton University. Einstein did not invite Vishniac, never having heard of him. Vishniac literally knocked on the famous scientist’s door and persuaded him to cooperate.

In 1947, the American Joint Distribution Committee commissioned him to visit displaced persons camps in Germany. During his trip, he also photographed the ruins and rubble of Berlin.

During the final phase of his career, he returned to his scientific roots and concentrated on microphotography.

Far from idolizing Vishniac, Bialis provides viewers with a fair and rounded picture of him. While she commends him for his portfolio of amazing photographs, she allows some family members to vent. They claim he was a “tremendous self-promotor” who “embroidered” the truth. “His exaggerations were enormous,” states Mara in a piercingly candid comment.

Certainly, Vishniac was a flawed individual in more ways than one, but his stellar contributions to photography and his outstanding achievement in preserving and memoralizing the images of pre-Holocaust Jewish communities are unassailable and have stood the test of time, as Vishniac strongly suggests.