Eighty years ago next month, the St. Louis, a luxury German passenger liner carrying more than 900 Jewish refugees, left the port of Hamburg bound for Havana, Cuba. The passengers, possessing valid Cuban visas, expected to be admitted to Cuba, but their hopes were cruelly dashed.

The Cuban government turned them away and the vessel headed toward Miami. Here, too, they were met with rejection. Their last hope for sanctuary, Canada, announced it would not admit them either. Finally, four European countries agreed to give them asylum, but this would not be the end of the story.

The plight of these German Jews is the subject of Maziar Bahari’s first-rate documentary, Voyage of the St. Louis, which will be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival on May 8.

The St. Louis incident is burned into the consciousness of Jews who believe that Western nations, such as the United States and Canada, treated imperilled European Jewish refugees with a mixture of callousness, cruelty and indifference. Proceeding from that assumption, Bahari has made a film that touches a deep chord.

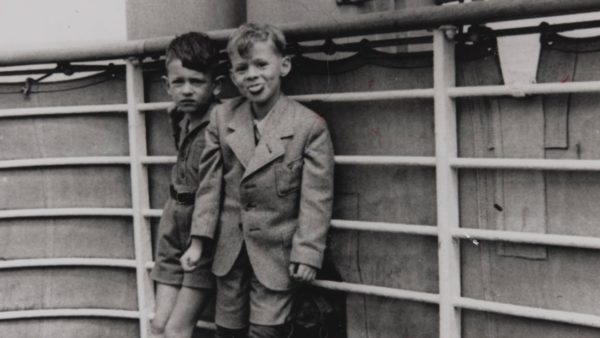

Capitalizing on a reunion of St. Louis survivors in Miami, he interviews passengers who embarked on an emotional rollercoaster after boarding the Hamburg-Amerika Line ship.

Herbert Karliner recalls that his father, a veteran of World War I, bought six Cuban visas for $500 each. “There was no future for us,” he says. As Heinz (Harry) Rosenbach boarded the St. Louis, he was so overcome with nervousness that he could hardly breathe. Gisela Feldman painfully had to leave her father behind in Germany.

A crew member of the St. Louis discloses he was instructed by German government officials not to fraternize with the passengers.

The St. Louis, flying a flag emblazoned with a swastika, steamed out of Hamburg on May 13, 1939, less than four months before the outbreak of World War II. The ship’s captain, Gustav Schroeder, an anti-Nazi, treated the Jewish passengers with respect.

A care-free atmosphere prevailed at the outset thanks to good weather, fine food and attentive service. “We were treated well,” says Saul Messinger.

A turn for the worse occurred when Moritz Weiler, a passenger who had been loathe to emigrate from his beloved homeland, died. His corpse, wrapped in a swastika flag, was lowered into the sea.

When the St. Louis reached Havana, passengers rejoiced. But they were thrown into despair upon being informed that they would not be permitted to land. The corrupt and venal Cuban interior minister, Manuel Benitez, had collected their fees for entry visas, but now the Cuban government refused to honor them. Benitez’s son, a Miami broadcaster, grudgingly admits his father pocketed the money to enrich himself.

Attempting to help the hapless refugees, the American Joint Distribution Committee and Schroeder intervened on their behalf, but to no avail.

Torn by anguish, a passenger slashed his wrists and jumped into the water in a suicide attempt. He was hospitalized in Havana, his family not permitted to join him.

The St. Louis left Havana, but many of the passengers were buoyed by hopes that the United States would admit them. Telegrams they sent to U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt and his wife asking for assistance were ignored.

When the St. Louis approached Miami, U.S. coast guard cutters blocked its route to the city’s port.

Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, having received an appeal from the passengers, referred the matter to the official in charge of immigration, Frederick Blair. Being an antisemite, he rejected their plea.

In desperation, some of the passengers considered setting fire to the St. Louis to prevent it from returning to Germany. Schroeder hatched a plan, soon abandoned, to dock the ship in Britain.

At this juncture, the American Joint Distribution Committee came to the rescue, convincing Britain, France, Holland and Belgium to admit the refugees. Those who were resettled in Britain survived the war, but many of the rest were murdered by the Nazis.

Schroeder guided the St. Louis back to Hamburg, but an Allied bombing raid destroyed it toward the close of the war. After Germany’s defeat, Schroeder was arrested by American occupation authorities, but was released after St. Louis survivors vouched for his character.

Voyage of the St. Louis takes us back to a time when antisemitism was dangerously common and acceptable and Jewish lives were expendable. It was an incredibly dark period, and Bahari’s vivid film brings it all back for us to ponder.