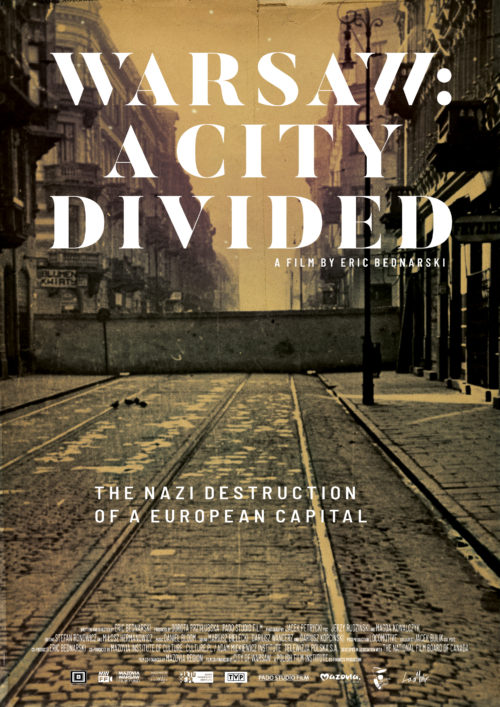

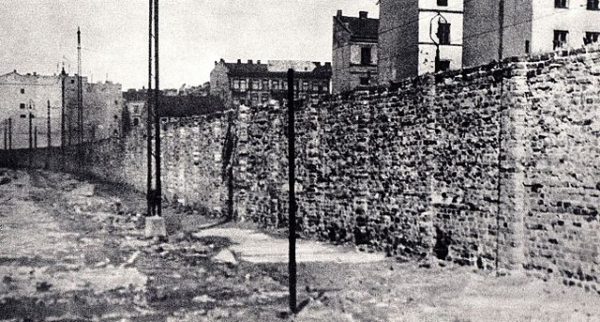

Eric Bednarski’s poignant documentary, Warsaw: A City Divided, due to be screened at the Jewish Film Festival in Jerusalem later this year, provides viewers with a fresh look at the Warsaw Ghetto. Established in 1940 on the cynically false rationale of halting the spread of infectious diseases, it was an overcrowded, walled-off dumping ground rife with misery and starvation and a way station to Nazi extermination camps.

In the summer of 1942, the Germans launched the first wave of massive deportations, sending its hapless Polish Jewish inhabitants to the Treblinka extermination camp. Less than a year later, a small cadre of Jewish militants rebelled in what would be known as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

The following summer, starting on August 1, a general uprising erupted in the Polish capital. It lasted for two months and was suppressed by the Germans.

Bednarski, a Canadian filmmaker of Polish origin based in Warsaw, uses these cataclysmic events to paint a vivid picture of a city that was virtually destroyed during the course of the brutal six-year Nazi occupation of Poland.

Focusing on the ghetto, he gives us a new perspective of it through the lens of footage shot by Warsaw resident Alfons Ziolkowski from March to November 1941.

“Fifteen years ago, I unearthed unique and hitherto unknown 8mm Polish amateur footage shot in … the ghetto soon after its creation by the Nazis,” Bednarski writes in his mission statement. “At its height, the ghetto would eventually hold some 450,000 Jews from Poland and elsewhere in Europe. Almost all of them would perish in the Holocaust. With my discovery of the footage came a strong sense of responsibility, not only to study and properly identify it, but above all to show it to the world. I have consulted with a wide range of experts, historical institutions, and museums in Poland, Britain and Israel over many years.

“Little is known about the intentions of the Polish amateur photographer who shot the footage, or about the circumstances in which it was shot. Alfons Ziolkowski died in the 1980s, leaving behind few details. What we do know is that, as a merchant, he was able to obtain a pass into the ghetto and, at great risk to himself, document scenes of daily life there. The material he produced differs in significant ways from the well-known footage later produced by Nazi German propaganda film crews in 1942. We are shown quite different locations, such as the Hale Mirowski Market area, a hub of essential food-smuggling activity, and unique views of the Okopowa Jewish Cemetery, today almost completely overgrown with trees. We discover the ghetto in an earlier phase of its existence, and not through the eyes of occupiers and perpetrators.”

Ziolkowski’s black-and-white footage is plain and unadorned, offering candid glimpses of everyday life in a ghetto doomed to be battered into rubble by its Nazi overlords.

People fill the sidewalks, going about their daily business. Men pull carts. Onlookers mill around a mound of potatoes on sale. A man lies prostrate on the street. A boy no older than 12 or 13 is seen running. A Jewish policeman in a spiffy uniform hits a boy who was probably a smuggler. (Eighty percent of the food consumed in the ghetto was imported from the Polish side). Another Jewish policeman stands next to a mass grave adjacent to a Jewish cemetery. A musician plays a violin.

In his film, Bednarski interweaves clips from Ziolkowski’s movie with contemporary views of Warsaw where the ghetto once stood. He also interviews Jewish survivors, nearly all of whom remained in Poland after the Holocaust. A woman sums up her experience by saying that her ordeal was one of humiliation, fear and hunger.

The ghetto was ordered destroyed by SS chieftain Heinrich Himmler, who contemptuously referred to its inmates as “sub-humans.” After about a month of fierce fighting, during which lightly-armed Jewish combatants inflicted painful casualties on the Germans, the resistance ended in surrender.

“The Jewish quarter of Warsaw is no more,” boasted German commander Jurgen Stroop, who was hanged after World War II.

Today, no more than a dozen of the ghetto’s original buildings are still intact. In honor of its victims, an empty tram emblazoned with a Star of David is driven through Warsaw once a year, on January 27, to commemorate Holocaust Memorial Day.

With the outbreak of the subsequent Polish uprising, the Germans were intent on laying waste to Warsaw, the symbol of Polish independence and sovereignty. “It was a landscape of ruins,” muses a man who witnessed the piecemeal destruction of the city.

The message Bedarski wants to leave is clear. As he writes, “I worked on this film for more than a decade, and by the time I was in the final stages of putting it together, it was clear that in a world where xenophobia, racism and antisemitism are once again on the rise, the task of sustaining the memory of tragedies such as that of the Warsaw Ghetto is more urgent than ever. Warsaw: A City Divided is one small contribution to the process of keeping alive that memory.”

Exactly.