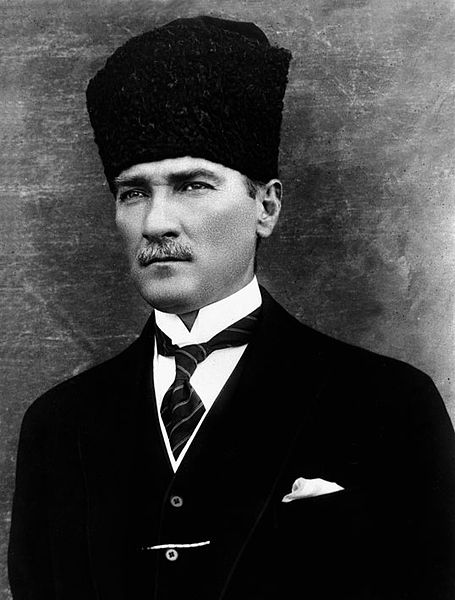

The founder of the modern Turkish state, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, died eight decades ago, on November 10, 1938. But is his legacy now being buried alongside him in his Ankara mausoleum?

Ataturk, known originally as Mustafa Kemal, built the Turkish Republic on the ruins of the decayed Ottoman Empire, which was defeated and stripped of its remaining Middle Eastern possessions in World War I. It was a time of great danger for the Turkish nation itself.

The victorious Allied powers planned to take possession of its capital, Istanbul, and even place much of its Anatolian heartland in the hands of foreign powers.

Mustafa Kemal was born in 1881 in Salonika. As a young man, he was involved with the Young Turks, a revolutionary group that deposed the sultan in 1909.

From 1909 to 1918, he held a number of posts in the Ottoman army. He fought against Italy in the Italo-Turkish War in 1911 and from 1912-1913 in the Balkan Wars.

In World War I, he made a name for himself as the commander of the 19th Division, where his bravery and strategic prowess helped thwart the Allied invasion of the Dardanelles in 1915.

The Treaty of Sèvres was imposed on the defeated Ottoman Empire in 1920. Under its provisions, the Turks were stripped of all non-Turkish possessions. But they also were obliged to cede much of Anatolia to Greeks, Armenians, and Kurds, as well as to Britain, France and Italy, which would possess zones of influence.

What particularly rankled the Turks was the clause giving Greece control over a large area of western Turkey, including the city of Smyrna (now Izmir).

Mustafa Kemal demanded that the Turks fight, and the subsequent war with Greece resulted in a Turkish victory. Armenian forces were also defeated.

In 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed, overturning the previous agreements, and resulting in total independence for the new Republic of Turkey. Mustafa Kemal became the country’s first president and would remain its leader until his death.

In creating a modern secular state, he ushered in reforms that modernized Turkey. He abolished the caliphate, banished religion from the public sphere, and looked westwards to Europe for inspiration. He also made polygamy illegal.

He introduced the Latin alphabet for the Turkish language, ordering all newspapers, books, and street signs printed in the new script. He ordered that girls be allowed to attend school and gave women the right to vote and take jobs in business and government. He forbade the Turkish people to wear fezzes, veils, or other traditional Turkish clothing.

He decreed that everyone must have a surname or family name. In 1934, the Turkish assembly gave Mustafa Kemal the name Ataturk, or “Father of the Turks.”

But Ataturk’s policy of state secularism was controversial, and he was accused of decimating important cultural traditions. It was viewed by his opponents as a form of anti-clericalism, destroying the Islamic cultural basis of Turkish nationhood.

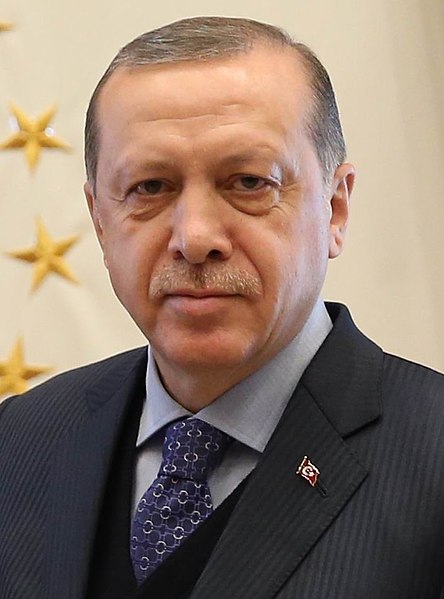

Are such people now reversing Ataturk’s work, with the Islamist President Recep Tayyip Erdogan now ruling the country in the manner of an Ottoman sultan?

In June, Erdogan was re-elected to another five-year term as president, with the sweeping new powers he won in a referendum in April 2017. This followed upon the massive purges of the country’s civil servants, academics, journalists, and teachers after the abortive coup in July 2016.

The 1982 constitution had established the country as a secular state and provides for freedom of belief and worship and the private dissemination of religious ideas.

But since 2016, Turkey’s democratic reversal has accelerated. Erdogan was emboldened by the decapitation of many in the military, a stronghold of Kemalist ideals, and the imprisonment of other opponents.

Erdogan’s governing Justice and Development (AK) Party could reshape Turkey for years to come. “Secularism was forced on the people as if it were a religion,” contends Fatma Benli, an Istanbul-based MP with the AKP.

His recent speeches have emphasized Turkey’s Ottoman history and domestic achievements over Western ideas and influences.

Such a prospect is anathema to secularists, with many asking whether Turkey is erasing the line between religion and state. Opposition groups have begun depicting Erdogan as a “neo-Ottoman” who seeks sweeping powers to change the country’s laws to reflect its growing Muslim identity.

In March 2014, Erdogan released a video suggesting he was leading Turkey’s “second war of independence,” shortly after an AKP press release referred to him as the “builder of Turkey.”

Erdogan has said one of his goals is to forge a “pious generation” in predominantly Muslim Turkey “that will work for the construction of a new civilization.” Religion classes have been made compulsory for children in public schools.

All of this involves returning Turks to their natural state of religiosity before Ataturk had changed them from what they were and always had been.

Under the AKP, the government’s Diyanet (Directorate of Religious Affairs), which trains imams, administers mosques and religious schools, and oversees Friday sermons, doubled its staff, with its annual budget increasing more than fourfold.

Since November 2017, the national police have been monitoring online commentary on religion and suppressing freedom of expression when they find such commentary “offensive to Islam.” Turkey’s state-controlled TV network, TRT, vilifies those who do not take part in Islamic practices.

Turkish officials have begun to call the country’s military deployment in Syria, which began on January 20, as “jihad.” The Dinayet ordered all of Turkey’s mosques to broadcast the “Al-Fath” verse from the Koran — the prayer of conquest — through the loudspeakers on their minarets.

All these new measures bode ill for the Kemalist tradition of secularism. Given the increasingly Islamic Turkey Erdogan has built — he calls it the “New Turkey” — the country today looks less and less like a liberal European democracy.

Said one AKP advisor to the author Shadi Hamid, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the author of Islamic Exceptionalism: How the Struggle Over Islam is Reshaping the World, “We need to carry Mr. Ataturk to his grave again.”

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.