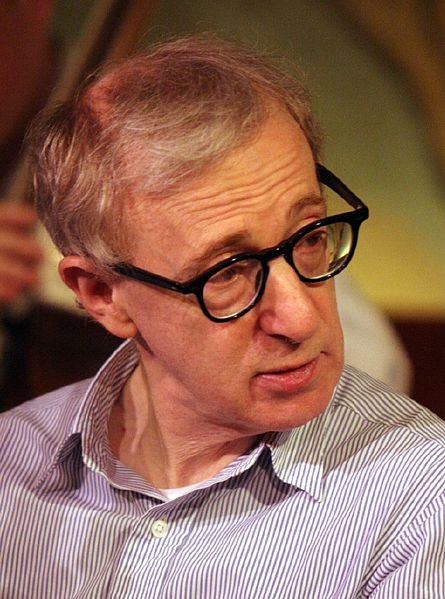

Woody Allen will be 80 next December and is still going strong. Indeed, he’s probably finishing his latest film script or movie as I write these words.

For about the past four decades, he’s turned out one movie per year, and like the old-school craftsmen he is, Allen composes his scripts on a yellow pad or on a battered old typewriter, cutting and pasting with a scissor.

No computers for him.

Allen, whose comedies have garnered a loyal following, is modest about his achievements. “It’s just story-telling,” he says nonchalantly. “It’s not quantum physics.”

This famous auteur is the subject of Robert Weide’s lengthy and substantive biopic, Woody Allen, which is now available on the Netflix streaming network.

Weide explores his boyhood in Brooklyn, his career in show business and his entry into filmmaking. Allen, a very shy person, has given Weide a lot of his time. Usually, he’s speaking from the back seat of a car in motion, but otherwise he’s seen in archival clips from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

Allen’s associates and ex-lovers, from the producer Robert Greenhut to the actress Diane Keaton, are added to the mix.

As Weide suggests, there are a multitude of Woody Allens — the precocious Jewish kid who churned out gags for newspaper gossip columnists like Walter Winchell and Leonard Lyons, the standup comedian who wowed audiences in Greenwich Village clubs, the clarinetist who performs virtually every Monday night at a Manhattan jazz club, and the director who’s won several Academy Awards.

Born in the Bronx and raised in Brooklyn’s Midwood district, he was known as Allan Steward Konigsberg before anglicizing his name. His grandparents, like many European Jews who settled in America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, emigrated from Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His parents, Martin and Nettie, were working-class people trapped in a bad marriage.

They hoped their son would be a pharmacist, but Allen wouldn’t cooperate. He hated school because some of his teachers were antisemites, says his sister, Letty, who works on his films as a producer.

By the age of 16, Allen was earning more than his father, a jack-of-all-trades, writing jokes for newspaper columnists, a public relations man and Arthur Godfrey’s radio program. As well, he wrote for the comedian Sid Caesar, whom he describes as a “comic genius.”

It all came easily to him. As he puts it, “I can write jokes. It’s like my normal conversation.”

Greatly influenced by the brash comedian Mort Sahl, Allen was initially averse to standup comedy, but as he developed self-confidence, he overcame his stage fright. He appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show and the Tonight Show, hosted by Johnny Carson.

“He was a completely new face,” says Jack Rollins, his co-manager.

Allen’s foray into Hollywood began when Charles Feldman, a producer, asked him to write the script for What’s New Pussycat? Allen gave himself a cameo role, launching him as an actor.

He was dismayed by the film, but was hooked on movies. In 1969, he directed his first film, Take the Money and Run, even though, as he now admits, he was a rank amateur. Barely pausing for breath, he successively directed Play It Again, Sam and Bananas. Since then, at his insistence, he’s has had full editorial control over his films.

In Weide’s judgment, Allen has been most influenced by the Marx brothers, Bob Hope and Ingmar Bergman.

Weide discusses the women in Allen’s life, from Louise Lasser to Mia Farrow, but barely mentions his current wife, Soon-Yi Previn, who was Farrow’s adopted daughter. His relationship with Soon-Yi precipitated a scandal, which Weide addresses.

In Weide’s estimation, Annie Hall (1977), the winner of four Academy Awards, probably shot him to stardom. Manhattan, released two years later, was acclaimed by critics and fans, too, but Allen claims he didn’t care for it. His commercially least popular film until that juncture, Stardust Memories, was his favorite one.

His films invariably unfold in New York City, but in recent years, Allen has set them in Europe. “The geography of the world inspires him,” says a film critic. But Allen’s decision to shoot in Paris, Rome and Barcelona was more prosaic, a function of dollars and cents because Manhattan has virtually priced itself out of the market.

Two thirds of the way into his documentary, Weide returns to Allen’s Protestant work ethic. Usually, he’s writing his next script as he’s directing his most current film. As his sister says, “The writing doesn’t take him long.” He does not suffer from writer’s block, she adds.

The director Martin Scorsese is amazed by his fecundity. “Not everyone has so much to say,” he observes. “Not everybody has his staying power and tenacity.”

Allen’s films became so repetitive and predictable after Deconstructing Harry (1997) that his producer urged him to slow down to one film every other year. He didn’t listen. Allen rebounded with Match Point (2005) and Midnight in Paris (2011), which has grossed more than any of his previous movies.

Allen is philosophic about box office receipts. “I don’t care about commercial success and rarely achieve it,” he muses.

Nonetheless, actors queue up in line to audition for roles in his films. “Everyone wants to work for him,” says Josh Brolin. “He’s one of those guys you want to please.”

According to Allen’s sister, he’s never been as happy as he is today. He’s on a roll, cinematically speaking, and he’s maritally content. “I’ve been very lucky,” Allen gushes, saying he’s living out his “childhood dreams.”

Can anyone ask for more?